Written by Jamie Kouba

“I have a project that I’m working on and I thought you might want to help”. That’s how it all started. Dr. Andrea Palmiotto asked me if I’d be interested in helping her work on a grant funded project. Honestly, I was just excited to help, I probably would have said yes to just about anything. Once I found out what the project was and that it involved archaeology and the law, I was completely sold! Due to the publicity that the

Arch Street Project received for the unexpected discovery of hundreds of human burials, members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly were made aware of certain complicating factors that must be dealt with when human remains are inadvertently discovered. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (CRP) is a bipartisan legislative agency that serves the Pennsylvania General Assembly in helping to create rural policy. In 2019, CRP tasked Dr. Palmiotto with providing a comprehensive assessment of Pennsylvania legislation related to human remains and burials, specifically those of archaeological concern, such as abandoned or forgotten cemeteries, or isolated and unmarked burials. Although there are federal laws regarding the discovery of archaeological remains, those laws only apply to projects that include federal involvement. In the state of Pennsylvania, there is no state-level legislation that adequately addresses the inadvertent discovery of archaeological remains on state owned, state-funded, state-assisted projects, or private property.

Arch Street Project received for the unexpected discovery of hundreds of human burials, members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly were made aware of certain complicating factors that must be dealt with when human remains are inadvertently discovered. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (CRP) is a bipartisan legislative agency that serves the Pennsylvania General Assembly in helping to create rural policy. In 2019, CRP tasked Dr. Palmiotto with providing a comprehensive assessment of Pennsylvania legislation related to human remains and burials, specifically those of archaeological concern, such as abandoned or forgotten cemeteries, or isolated and unmarked burials. Although there are federal laws regarding the discovery of archaeological remains, those laws only apply to projects that include federal involvement. In the state of Pennsylvania, there is no state-level legislation that adequately addresses the inadvertent discovery of archaeological remains on state owned, state-funded, state-assisted projects, or private property.

After some conversations about what we thought Pennsylvania was missing, in terms of legislation, we ended up with more questions than answers. What is supposed to happen when human remains are discovered? Who is in charge? What happens to those remains after a disinterment? Dr. Palmiotto and

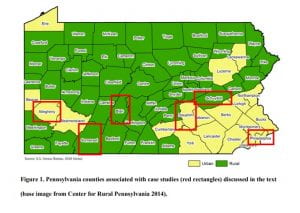

I made a list of agencies in Pennsylvania and other states that we needed to contact in order to gather case studies, and we got to work. Due to the pandemic, we couldn’t meet with any of these agencies in person. Luckily, we had technology and so we did months of research and interviews through emails and Zoom. We gathered dozens of stories, field reports, and news articles and we started to assess which laws were applied to each project and why. As it turned out, because there was only a web of partially intersecting local laws, state laws, and standard operating procedures among different agencies, every case was handled differently. It was really interesting to see how different agencies interpreted that patch work of laws and put them to use. Seeing how each of the projects were handled with the utmost care and respect for the deceased was wonderfully reassuring to my faith that modern archaeology is not grave robbing.

It took about nine months; but at the end of it, we submitted a completed report to CRP that outlined the existing laws and standard operating procedures that are currently being utilized in Pennsylvania and in other states, as well as making recommendations for new legislation that will help to create best practices for the future of archaeological burials. Copies of our report were published by Pennsylvania General Assembly and sent to other state agencies. It is our hope that these recommendations will be used to guide Pennsylvania in the respectful and efficient recovery of human remains. Although Dr. Palmiotto and I didn’t use any trowels, our digging into the Pennsylvania’s laws and regulations regarding archaeological remains will serve the future archaeological record. And for that, I’m so very grateful that I got the chance to work on this project.

The article can be found here: Historic-and-Archaeological-Human-Remains-2021.pdf (palegislature.us)

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram