With President Biden officially recognizing October 11th as Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we question what may happen to Columbus Day, typically celebrated on the second Monday of October. Several states have been celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day for years in protest of Columbus Day, saying the Christopher Columbus “brought genocide and colonization to communities that had been in the United States for thousands of years.” Columbus Day has been celebrated as a federal holiday since 1968, and as a national holiday from 1934, from the belief “that the nation would be honoring the courage and determination which enabled generation of immigrants from many nations to find freedom and opportunity in America.”

At a United Nations conference in 1977 idea of an Indigenous Peoples’ Day was first proposed by a delegation of Native nations. In 1990, South Dakota became the first state to observe Native American Day. Columbus Day is a federally recognized holiday, and Indigenous Peoples’ Day is not, however there is proposed bill from Congress in the works. Although, U.S. cities and states can choose to observe or not to observe federal holidays.

Indigenous people have protested Columbus Day for many years, and favor a complete transformation of the holiday, rather than a separate celebration for both. Many wonder whether this acknowledgement from the President is actually doing enough for the Indigenous, while other see it is a promising beginning. Jonathan Nez, president of the Navajo Nation stated, “transforming Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day will encourage young Navajos to have pride in the place and people they come from and the beauty they hold within.” While the proclamation does not address issues Indigenous people face with land, water, or female disappearances, some believe that it will help bring awareness to these problems.

Many Italians support Columbus Day and others have called for an Italian Heritage Day, to still allows them to celebrate their heritage. After an 1891 lynching of 11 Italians in New Orleans, many Columbus statues were erected. The president of the National Italian American Foundation stated, “Columbus represented their assimilation into the American fabric and into the American dream.” He believes that Indigenous Peoples’ Day should not “come at the expense of a day that is significant for millions of Italian-Americans” and that the Indigenous are still worthy of their own holiday to “celebrate their contributions to America.”

Some have taken to calling this day of the year both Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Italian Heritage Day. Festivities across the U.S. today still include celebrations for all three titles.

What do you think?

Do you think Columbus Day should be forgotten, despite its intention towards “commemorating the country’s spirit of exploration and honoring Italian-Americans?” Should all three titles be used and celebrated on the same day? Will Indigenous Peoples’ Day increase advocacy toward Indigenous efforts?

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Further Reading:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/us/indigenous-peoples-day.html

https://www.wsj.com/articles/columbus-day-indigenious-peoples-day-what-to-know-11633787027#:~:text=When%20Congress%20officially%20made%20Columbus,to%20the%20Congressional%20Research%20Service.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/10/08/a-proclamation-indigenous-peoples-day-2021/

https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/11/us/indigenous-peoples-day-2021-states-trnd/index.html

https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/informational/columbus-day-myths

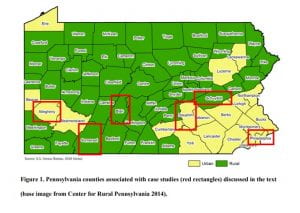

Arch Street Project received for the unexpected discovery of hundreds of human burials, members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly were made aware of certain complicating factors that must be dealt with when human remains are inadvertently discovered. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (CRP) is a bipartisan legislative agency that serves the Pennsylvania General Assembly in helping to create rural policy. In 2019, CRP tasked Dr. Palmiotto with providing a comprehensive assessment of Pennsylvania legislation related to human remains and burials, specifically those of archaeological concern, such as abandoned or forgotten cemeteries, or isolated and unmarked burials. Although there are federal laws regarding the discovery of archaeological remains, those laws only apply to projects that include federal involvement. In the state of Pennsylvania, there is no state-level legislation that adequately addresses the inadvertent discovery of archaeological remains on state owned, state-funded, state-assisted projects, or private property.

Arch Street Project received for the unexpected discovery of hundreds of human burials, members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly were made aware of certain complicating factors that must be dealt with when human remains are inadvertently discovered. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (CRP) is a bipartisan legislative agency that serves the Pennsylvania General Assembly in helping to create rural policy. In 2019, CRP tasked Dr. Palmiotto with providing a comprehensive assessment of Pennsylvania legislation related to human remains and burials, specifically those of archaeological concern, such as abandoned or forgotten cemeteries, or isolated and unmarked burials. Although there are federal laws regarding the discovery of archaeological remains, those laws only apply to projects that include federal involvement. In the state of Pennsylvania, there is no state-level legislation that adequately addresses the inadvertent discovery of archaeological remains on state owned, state-funded, state-assisted projects, or private property.