On October 5th, the Pennsylvania Archaeological Council held their first in a series of four programs in honor of 2021 Virtual Archaeology Month. This session was titled 3D Archaeology: Tech, Techniques, and Applications for Artec3D Scanners, and was led by Lisa Saladino Haney, Ph.D., assistant curator of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Josh Cannon Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh Honors College.

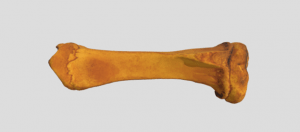

Haney started by describing the types of 3D scanners that she is using and that could be applied to future field archaeology projects. These Artec3D scanners are the Space Spider and Eva. The Space Spider is a handheld, portable scanner that uses blue light technology that works best when scanning smaller objects or finer textures or details. It also works well with complex geometry, sharp edges, and incised ceramics. It has internal temperature stabilization, meaning it works well in the winter and summer. The Eva works better with larger objects and is also portable. It uses structured light scanning technology to capture its images. Because of its larger field of vision, it can capture more in less time. Combining both scanners allow for the collection of even more details. The presenters stated that these scanners work much better with shiny surfaces than photogrammetry. Overall, the scanners capture reflective surfaces, have a higher level of accuracy, and work faster in post-processing than photogrammetry.

Dr. Haney and Dr. Cannon are working with University of Pittsburg honor students in a museum internship program to instruct them on how to use this technology, and once trained can hopefully send them to other sections of the Carnegie Museum where needed. Projects the scanners are being used for right now include an exhibition titled From Egypt to Pittsburgh, in which the team are scanning small fragments from a 1922 excavation from an Egyptian city called Amarna, in the hopes that the pulverized royal statuary pieces can be reconstructed and used for future research. Another project, Egypt on the Nile, plans on scanning a model of a Dahshur funerary boat to create both a virtual and physical model. They also plan to use the scanners to scan broken pot pieces to then create magnetic replicas that can be used to “put the pot back together” in a sort of puzzle, increasing accessibility and the chance to interact with ‘artifacts’ for the public.

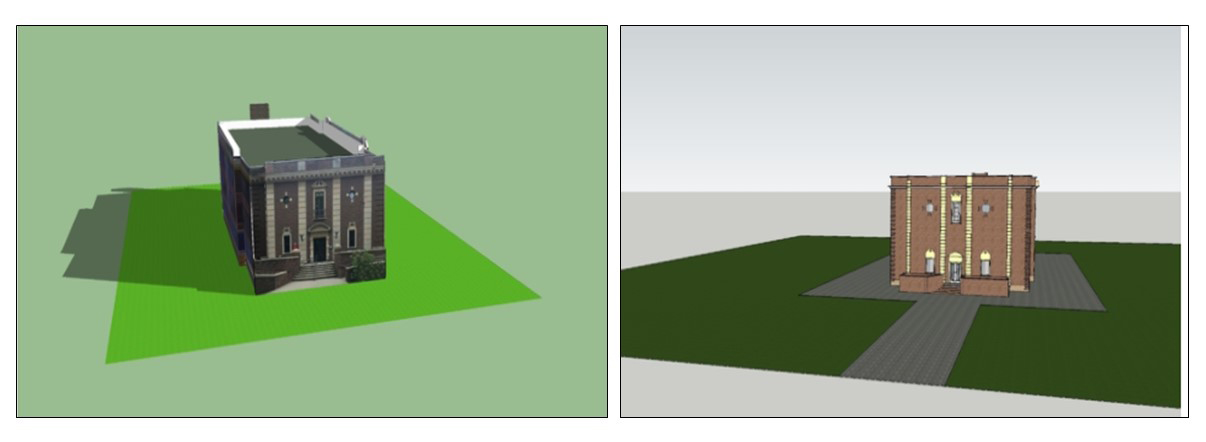

The 3D models created from the scanners are extremely accurate, with precise and detailed measurements. This allows the data from the models to be of high quality scientifically, making them great for sharing to researchers around the world, especially in times of covid where travel and use of collections is limited. The models also aid with conservation efforts, allowing pieces to be brought out, scanned, and then put safely away, with the data being used for study and public engagement. Aligning pottery sherds with the Artec3D software that are difficult to glue together, was also illustrated as a positive example of the scanners’ possibilities.

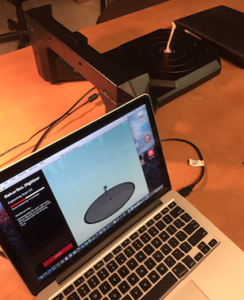

The application for scanners to be used in the field during an archaeological excavation is promising. The scanners could be used to record small finds quickly and could also be used to scan things in situ. The models produced are more detailed, more accurate, and can be done faster than hand drawings. For archeological field surveys, battery packs can be attached to belts to make the light scanners portable and give archaeologists the ability to scan in real time. However, a laptop is needed to be attached as well, to upload the scanned data. The scanner captures images instantly, the Eva can do a square meter at a time. Josh Cannon predicted that it could scan a hearth in about ten minutes. While the scanners can handle temperature changes, it might not fare well with elements like sand or dust, but if taken care of can last a long time.

The files of data from the scans are large, and therefore external storage sources are required to remove data from laptops. If files are kept on laptops, processing times will be slowed as the hard drive fills up. The presentation ended with the viewing of a scan of a wolverine skull. It took eight different scans over an hour to create the entire skull. Even the smallest details were visible, and it took up over 1 GB of data.

The presentation was incredibly interesting, and hopefully this technology will be used to aid archaeological excavations in the future. Please consider registering for the other three programs being held throughout the month of October!

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

https://sourcegraphics.com/3d/scanners/artec/eva/

https://www.javelin-tech.com/3d/3d-scanners/artec-space-spider/