Written by Gage Heuy

This week marked a major anniversary for archaeologists and the Tribal Nations whom they work with: the 30th anniversary of the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Starting November 16th, 1990, the world of cultural resource management would forever be changed with the forging of new relationships between Native Americans,

museums, archaeologists, and federal agencies. NAGPRA ensures that human remains, grave goods, and other objects of cultural patrimony (defined in the act as “an object having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than property owned by an individual) (NAGPRA Sec. 3001.) found on federal land or residing within federally funded institutions is repatriated to the Tribal Nation or Organization whose members or ancestors are associated with those remains or cultural items. In fact, this law goes even further to clearly state that the lineal descendants of those ancestors or the Tribal Nation associated with those remains or sacred objects are the rightful owners of any human remains, funerary objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. This is a far cry from the early days of archaeology and museums where the objects found during excavation (regardless of how significant they were to living peoples) belonged to the archaeologist who “discovered” them, or the museums who accessioned them into their collections. In the 30 years since NAGPRA became law, the culture within archaeology has taken a dramatic shift, where more and more professionals within academia, museums, and CRM understand the necessity to respect the ancestors and material culture of Native Americans and are committed to working alongside their governments to ensure that this respect informs every step of the NAGPRA process.

museums, archaeologists, and federal agencies. NAGPRA ensures that human remains, grave goods, and other objects of cultural patrimony (defined in the act as “an object having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than property owned by an individual) (NAGPRA Sec. 3001.) found on federal land or residing within federally funded institutions is repatriated to the Tribal Nation or Organization whose members or ancestors are associated with those remains or cultural items. In fact, this law goes even further to clearly state that the lineal descendants of those ancestors or the Tribal Nation associated with those remains or sacred objects are the rightful owners of any human remains, funerary objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. This is a far cry from the early days of archaeology and museums where the objects found during excavation (regardless of how significant they were to living peoples) belonged to the archaeologist who “discovered” them, or the museums who accessioned them into their collections. In the 30 years since NAGPRA became law, the culture within archaeology has taken a dramatic shift, where more and more professionals within academia, museums, and CRM understand the necessity to respect the ancestors and material culture of Native Americans and are committed to working alongside their governments to ensure that this respect informs every step of the NAGPRA process.

The law outlines a process that requires special cooperation between archaeologists and Indigenous communities that ultimately results in repatriation, or a “giving back” of the ancestors or sacred objects. Repatriation looks different on a case to case basis, but essentially, any institution who  receives federal funding (be that museums, universities, etc.) must compile an Inventory of Indigenous human remains and associated funerary objects; identifying any ancestors or associated funerary objects present within their collections and formally reaching out to the Federally Recognized Tribe or Nation with a possible cultural or geographic relation to the individual whose remains are held by the agency. Once face to face consultation is initiated in accordance with the principles of Government to Government consultation, a determination is made on whether or not the individual(s) held in the collections can be culturally affiliated, meaning that a relationship of shared identity can be traced from the deceased individual’s culture and a present-day Federally Recognized Tribe or Native Hawaiian Organization (NHO).

receives federal funding (be that museums, universities, etc.) must compile an Inventory of Indigenous human remains and associated funerary objects; identifying any ancestors or associated funerary objects present within their collections and formally reaching out to the Federally Recognized Tribe or Nation with a possible cultural or geographic relation to the individual whose remains are held by the agency. Once face to face consultation is initiated in accordance with the principles of Government to Government consultation, a determination is made on whether or not the individual(s) held in the collections can be culturally affiliated, meaning that a relationship of shared identity can be traced from the deceased individual’s culture and a present-day Federally Recognized Tribe or Native Hawaiian Organization (NHO).

In a case where association of an individual cannot be linked to a Federally Recognized Tribe, those individuals and any items that they were interred with are referred to as “Culturally Unidentifiable”. A museum or federal agency who currently houses “Culturally Unidentifiable” ancestors and funerary objects must offer to transfer those remains and objects to either the Federally Recognized Tribes whose present Tribal lands the individual was buried and subsequently removed from or the Tribe(s) whose ancestral lands the individual was discovered on. The Summary process is similar, though instead of specific ancestral individuals and associated funerary objects, this process is concerned with unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and other objects of cultural patrimony. A summary is simply a general description of what objects in those categories are present within the holdings or collections of museums or Federal agencies that serves as an invitation to begin a consultation process with the Federally Recognized Native American Tribes, Native Alaskan Villages, or Native Hawaiian Organizations. Lastly, NAGPRA prohibits the removal of Indigenous remains or culturally sensitive items on Federally or Tribally owned lands without first receiving a permit issued under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA). Once the permit is received, consultation is still required to ensure that the remains or artifacts are handled properly and eventually repatriated. The law also outlines a process that archaeologists and CRM professionals must follow in the event of an inadvertent discovery of human remains. It states that the appropriate Federal agency or Tribal official must be contacted immediately and the project that disturbed the remains or objects is halted until consultation takes place in order to develop a plan for the safety and proper disposition of the individual.

Repatriation and burial service. Source: nps.gov

While NAGPRA is seen as a great improvement in the relationships between Federal agencies, archaeologists, and Indigenous peoples, it hasn’t always been viewed favorably in the three decades since it was passed. One critique of NAGPRA that was very common throughout the 1990s and 2000s is that this law undermines scientific authority and is a determent to archaeological and bioarcheological research because it removes artifacts and remains for the realm of research. This critique is not entirely well founded and stems from problematic ideas about archaeologists’ role in the removal and study of Indigenous bodies and cultural goods. Archaeologists and anthropologists have a long history of claiming ownership over Indigenous remains and the material culture that was interred with the deceased. NAGPRA reasserts Indigenous sovereignty over their ancestors’ remains and possessions, and from the perspective of some (see Gonzalez and Marek-Martinez 2015), the NAGPRA process actually provides an opportunity for archaeologists to develop new kinds of research questions and to work alongside Indigenous peoples as that research is developed.

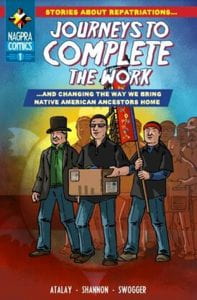

Repatriation Comic Link here

While archaeologists seem to have finally come around to embracing this re-assertion of Indigenous sovereignty, there are still hundreds of thousands of Native ancestors whose remains are currently held by Federally funded museums, universities, and agencies. Nationwide, it is assumed that 60% (around 120,000 individuals) of the ancestors held by universities, museums, and other institutions have not been returned to Tribes through the NAGPRA process. This could be due to a number of reasons, but regardless of the reasoning, it is clear that much more work is to be done in returning ancestors to Tribal Nations and respecting the sovereignty of Native Americans. I firmly believe that the next 30 years of NAGPRA will see an increase in awareness, respect, and accountability on the part of settler archaeologists who are finally coming around to understanding our role in the ongoing colonization of the Indigenous peoples of this continent.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

For more information about NAGPRA see:

Carrying our Ancestors Home, Association for Indian Affairs, 30 Years of NAGPRA Discussion w/ ArchyFantasies and Dr. Krystiana Krupa, The National NAGPRA Program