Let’s dig into some history about the famous gobbling bird, the holiday we love to eat it on, and the archaeology of the area the tradition originated from!

The modern domestic turkeys we see today are descended from ones domesticated by Mayans in Mexico around 2,000 years ago. Evidence for Turkey domestication has also been dated to around 2,000 years ago in the American Southwest, Four Corners region, by the Ancestral Puebloans. Sites like Basketmaker III sites have included evidence such as

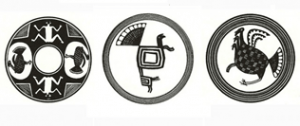

Designs incorporating turkeys from black-on-white bowls made during the Classic Mimbres phase in southwestern New Mexico, as drawn in essays by Jesse Walter Fewkes, published by the Smithsonian in 1923 and 1924.

droppings, eggshells, and feathers. Turkeys were kept for food but also most likely valued for their feathers, used for ritual objects and even textiles. It has also been argued that turkeys were used in ritual sacrifices.

The earliest evidence of the Mexican turkey in the ancient Mayan world is from turkey bones discovered by archaeologists at the site of EL Mirador in Guatemala, dating to 300 B.C. to 100 A.D. Along with archaeological, zooarchaeological, and ancient DNA, researchers were able to determine that the non-local turkeys indicate a Preclassic exchange of animals between northern Mesoamerica and the Maya cultural region. The evidence represents the earliest Mesoamerican domestication and rearing of turkeys and provides information on long-distance trade connections.

The original Thanksgiving dinner or Harvest Feast that lasted for three days at the Plymouth Colony in 1621 was most certainly smaller and less varied than what we gorge on today. An English leader who was present at the meal, Edward Winslow, wrote in a letter to a friend, “Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruits of our labors…many of the Indians coming amongst us…for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer.” Turkeys were mentioned by William Bradford of Plymouth while describing the 1621 autumn, “And besides waterfowl, there was great store of wild Turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison,” increasing the chance that turkeys were present at the meal.

Today, archaeologists and graduate students with the University of Massachusetts-Boston excavate undeveloped lots on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, near the National Historic Landmarks site which includes the Pilgrims first cemetery which was a Wampanoag Village thousands of years before. With plans for a permanent memorial titled Remembrance Park, opportunities for excavations are becoming more limited. The Park will focus on The Great Dying of 1616-1619 when diseases from Europeans plagued the Wampanoag and killed around 50,000, the first and harsh winter the Pilgrims experience in 1620-162, and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

The construction of the park is scheduled for 2023 unless archaeologists make extraordinary finds. Linda Coombs, a Wampanoag tribal leader and activist states, “The Park is intended to acknowledge and preserve what we’ve all lived through in 2020. It’s an opportunity to bring the past and present together in ways we never could have foreseen.”

So please enjoy your turkey this Thanksgiving, but do not forget the history behind the holiday!

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Further Reading:

What has long puzzled archaeologists is why prehistoric people went to so much work to dig pits down to bedrock when it could have been more easily collected from the surface. The other question of interest is why they quarried in some locations and not others where rhyolite outcrops. In order to help answer these questions, and with a permit from the PA SHPO and DCNR, Paul Marr of Shippensburg University began excavating the Green Cabi

What has long puzzled archaeologists is why prehistoric people went to so much work to dig pits down to bedrock when it could have been more easily collected from the surface. The other question of interest is why they quarried in some locations and not others where rhyolite outcrops. In order to help answer these questions, and with a permit from the PA SHPO and DCNR, Paul Marr of Shippensburg University began excavating the Green Cabi