Spring has finally arrived, and we have had some nice days here at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Spring is my favorite time of year, with crocuses blooming and the snow finally shifting into rain. Equinoxes, like the spring equinox, are recognized by many Native cultures for various reasons, so I wanted to learn about some Native American spring myths and legends.

Spring has finally arrived, and we have had some nice days here at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Spring is my favorite time of year, with crocuses blooming and the snow finally shifting into rain. Equinoxes, like the spring equinox, are recognized by many Native cultures for various reasons, so I wanted to learn about some Native American spring myths and legends.

One Chippewa Legend tells the story of a cold, old man encountering a young man as he entered his lodge. As they smoked a pipe, the old man said that he was Peboan, the Spirit of Winter, while the younger man said he was Seegwun, the Sprit of Spring. They described their abilities; how one shakes their locks and snow blankets the land, while the other shakes their ringlets and warm rain showers fall. As they spoke the weather changed and Peboan and his lodge dissolved and faded into tiny streams of water, leaving behind the first blossoms of spring as Seegwun grew stronger and more radiant.

Another legend is based on a tribe from the south-western country in Texas, and tells of a time when the beginning of spring was met with bitter cold days, making the people of the tribe suffer from great hunger. The tribe’s medicine man beat his drum and called to the Great Spirit. The Great Spirit responded and told him that there was no rain, flowers, or animals, because the tribe had angered him. But, by giving the Great Spirit a burnt offering of something they love and scatter the ashes, then this will please him. A little girl heard what the medicine man had said and realized that she would have to sacrifice her kachina doll, because she felt that nothing could be more loved than it. She sacrificed her doll, and after the ashes had blown away in the wind, the ground began to warm, the smell of spring spread, and a misty rain fell. On the hills around the camp a new flower was growing. They grew in the shape of the little bonnet of feathers her doll had worn. They were blue like the color of feathers, with a speck of red at the center for the fire it had burned in and tipped with silver gray like the ashes that were left behind. The Indians named them bluebonnets and the town knew what the little girl had done. Whenever these flowers appear, the Great Sprit has brought spring.

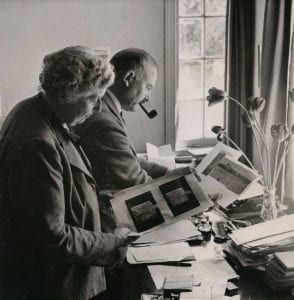

Because we are still in Women’s History month, I also wanted to include this excerpt from our recent Instagram post, written by fellow graduate student Mikala Hardie, about Bertha Parker Cody who is considered the first Native American female archaeologist. She was of Abenaki and Seneca descent and first learned about archaeology in the field when her uncle took her on one of his digs at a Mesa House site. She is most well known for her discovery at the Gypsum cave site in 1930. Here, she found an ancient ground sloth skull next to human-made tools suggesting that early humans inhabited the United States much earlier than previously thought. In 1933 the Southwest Museum hired her to write up reports of the Gypsum cave site and catalog the artifacts found there. Throughout the rest of her professional career, she wrote a number of articles about the Native American tribes found in California. Currently, she is honored through the SAA’s “Bertha Parker Cody Award for Native American Women”.

Because we are still in Women’s History month, I also wanted to include this excerpt from our recent Instagram post, written by fellow graduate student Mikala Hardie, about Bertha Parker Cody who is considered the first Native American female archaeologist. She was of Abenaki and Seneca descent and first learned about archaeology in the field when her uncle took her on one of his digs at a Mesa House site. She is most well known for her discovery at the Gypsum cave site in 1930. Here, she found an ancient ground sloth skull next to human-made tools suggesting that early humans inhabited the United States much earlier than previously thought. In 1933 the Southwest Museum hired her to write up reports of the Gypsum cave site and catalog the artifacts found there. Throughout the rest of her professional career, she wrote a number of articles about the Native American tribes found in California. Currently, she is honored through the SAA’s “Bertha Parker Cody Award for Native American Women”.

I wish you all the best spring!

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Further Reading:

https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/TheSpringBeauty-Chippewa.html

http://whisperingbooks.com/Show_Page/?book=Native_American_Legends&story=Kachina_Brings_The_Spring