2015 IUP excavations at Hanna’s Town

Hanna’s Town is arguably the most important historical site in Westmoreland County. As the first British county seat west of the Allegheny Mountains, a toehold for Anglo American western expansion, and the home of the Hanna’s Town Resolves it played important judicial, economic, social, military, and cultural roles in the formation of western Pennsylvania. Robert Hanna purchased a tract of land along the Forbes Military Road at the head of a branch of Crabtree Creek in 1769. Situated between Fort Pitt and Fort Ligonier, Hanna’s tavern Hanna’s became the county seat when Westmoreland County divided from Bedford County in 1773. Hanna also began selling lots in the town that year and Hanna’s Town quickly took shape. As county seat, Hanna’s Town was the site of the county’s first courts, which were “at least an occasional destination for settlers living throughout the southwestern part of [Pennsylvania]” (Carlisle 2005:1). Due to the necessity of occasionally visiting the court for criminal proceedings or land transactions, as well as the settlement’s position along one of the major overland routes to the Northwest Territory, Hanna’s Town developed into a thriving community with approximately 30 homes, a stockade fort, and multiple taverns. A month after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the inhabitants of Westmoreland County adopted the Hanna’s Town Resolves on May 16, 1775. Signed at Hanna’s Town, this document declared that the citizens were “resolved” to resist the tyranny of Britain. The citizens’ resolve continued throughout the war with local men joining local militias and participating in battles throughout the Northwest Territory. In response to these battles as well as American attacks on Native settlements, Hanna’s Town became the target of one of the final acts of aggression in the American Revolution. On July 13, 1782 a raiding party of Native and British soldiers led by Seneca Chief Sayenqueraght attacked the town, burning its buildings and slaughtering livestock. Hanna’s Town never fully recovered from this attack, and was subsequently abandoned as the state road and county seat shifted to Greensburg. Following its abandonment, the land was farmed until its purchase by Westmoreland County in 1969.

IUP excavations at Hanna’s Town since 2011

IUP entered into an agreement with WCHS in 2011 to provide IUP students and faculty with access to the Hanna’s Town site and associated artifact collections while providing WCHS with new archaeological interpretations and ways to increase awareness of the site’s significance. This is an ongoing relationship with many facets ranging from the creation of a digital artifact catalog and map to consultation regarding ground-disturbing maintenance at the park, but the most important aspect of IUP’s involvement with Hanna’s Town has been hands-on student education through field schools, class projects, theses, and work experience.

Hanna’s Town has also been the subject of seven graduate theses at IUP. These theses cover a range of topics from buttons to geophysics. Two students, Renate Beyer and Stefanie Smith, have completed their theses. Renate reanalyzed the glass and ceramics from the Foreman’s Tavern pits to compare them with a tavern closer to Philadelphia. She found that the Foreman’s were adopting new fashions almost as quickly as their eastern counterparts and that new types of ceramics first appeared in showier pieces such as tea services. Stefanie examined animal bones from the Foreman’s Tavern, Hanna’s Tavern, and Irish House portions of the site to explore variations in diet among the townspeople. Her results showed that most people were eating a mixture of domestic and wild animals, but that the Irish House inhabitants ate significantly more domestic animals than their neighbors. These results suggest that Irish House was inhabited later than the other buildings, an idea supported by the predominance of pearlware, a type of ceramic not introduced to North America until 1780, near this structure. Her research also revealed a substantial number of grey squirrel bones in the Foreman’s Tavern deposits, suggesting that squirrel may have been served in the tavern.

Students excavating at Hanna’s Town in 2013

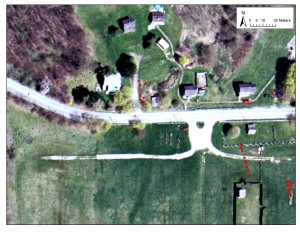

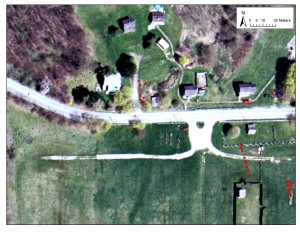

The other theses are still underway but are showing promising results. Ashley Taylor has used a variety of geophysical techniques to investigate the Hanna’s Town cemetery. The cemetery is of particular importance because it is the last aboveground physical link with the original town. Ashley’s research showed that the cemetery was once larger than the current boundary implies by finding several grave shafts outside of the fence. David Breitkreutz is also applying geophysics to give us a better understanding of the site’s layout (Figure 6). Taking advantage of a large ground-penetrating radar recently acquired by IUP, one of only two in the US, he has surveyed much of the area south of Forbes Trail Road. This survey covers areas never before excavated and will be used to guide our 2017 field school excavations. Three other graduate students are focusing on artifacts from the collection. Jay Taylor is analyzing the metal artifacts to better understand what occupations were practiced in the town. Nichole Keener is studying the buttons and other fasteners to reconstruct the clothing of Hanna’s Town residents. Cheryl Frankum is conducting an elemental analysis of redware from the site. Redware, the Tupperware of the 18th century, is the most common artifact in the collection and also the least studied. Cheryl’s research is a first attempt at understanding this important type of artifact and may shed light on where the pots, jars, bowls, and other pieces were coming from.

There are also three undergraduate theses about Hanna’s Town in progress. While undergraduates are not required to complete a thesis doing so gives them an advantage in applying for jobs and graduate school because it shows that they can take a research project from plan to completion. James Miller is studying the distribution of expensive ceramics across the site to determine if there was class variation at Hanna’s Town. Kelsey Schneehagen is looking at Hanna’s Town in a regional context to explore relationships with other settlements in western Pennsylvania. Eden VanTries is studying the people who lived at Hanna’s Town before Hanna (or even his predecessor, Jacob Miers). In the course of previous excavations several stone tools have been recovered. Eden is analyzing these artifacts to understand when previous groups lived on the ground that became Hanna’s Town. As these graduate and undergraduate theses are completed copies are filed with the WCHS so that they are available to other researchers.