This is my second and final summer leading the PHAST crew. PHAST (Pennsylvania Highway Archaeological Survey Team) is an archaeological survey program created through an inter-agency partnership between Pennsylvania’s Department of Transportation (PennDOT) and IUP. Each summer, 3 crew members and a field director (that’s me) take on a list of small archaeological surveys required by State and Federal regulations for PennDOT projects which propose ground disturbance. The crew this summer are all graduate students at IUP who have just completed their first of two years: Steven Campbell, Sam Edwards, and Kristina Gaugler. Most of our projects are bridge replacements and intersection realignment that do not have a large footprint. This gives us many opportunities to work in different parts of the State. Oftentimes in cultural resource management those working in the field are less involved in the lab work and report writing, so the holistic experience offered by the PHAST program is one of it’s biggest draws.

Since mid-May, we have completed the fieldwork for 4 projects, finding one archaeological site in the process: a multi-component site with both prehistoric and historic artifacts present. A rainy month of June has slowed us down some, forcing us to search for drier portions of the Commonwealth. Unlike Dr. Ford, none of our crew is qualified to conduct underwater archaeology…

After a few weeks working in the center of the state and dealing with a flooded project area, we headed to Wyoming County in the northeast corner of Pennsylvania. After the fourth of July, PHAST will begin a project in Venango County in the northwest corner of the state. In addition to our growing list of hotels to stay in (or avoid staying in) and the good eats in small towns across Pennsylvania, our travels force us to become familiar with several regions of the state.

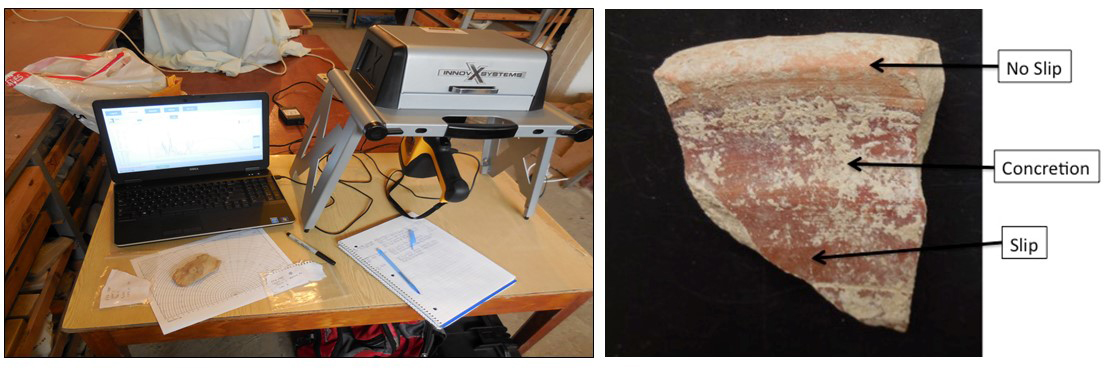

Our background research, fieldwork, and reporting require us to learn about the environments we are working in in order to interpret the soils and artifacts we unearth in our excavations. Upon encountering a field full of chert, a material often used to produce stone tools, further research into the bedrock geology along with analysis of the samples we collected allowed us to determine that the chert was naturally-occurring and unrelated to human modification. Working in floodplains along creek sides we must pay attention to geologic factors which influence the routes of waterways over time, historic deforestation and mining across the state, and more recent events such as Hurricane Agnes which caused significant flooding along waterways in Pennsylvania.

Running the PHAST crew is an excellent learning experience, constantly forcing me to adapt to new situations and solve unexpected problems as they arise. The network of support from the university, from PennDOT, and from the crew is what keeps everything running smoothly – ensuring that it is not only a learning experience, but a productive component of PennDOT’s cultural resource management program. In addition to the educational benefits it provides, and the contributions PHAST makes to interpreting the archaeology of Pennsylvania, the program also helps to save money. As an in-house program utilizing student interns, PHAST is able to complete projects required by Federal and State regulations for a fraction of the cost if a private company were to do the same job. In doing so it also helps to train students to work in the cultural resource management industry spreading the benefits across state and agency lines.