Has anyone watched the movie Death on the Nile recently? Agatha Christie’s 1937 fictional detective story set in Egypt was recently taken to the big screen, sure to wow any audience, archaeologists included! But did you know that Christie has a strong connection to the world of archaeology, which influenced many of her novels other than Death on the Nile, such as Murder in Mesopotamia, published in 1936, where an archaeologist’s wife is killed, and Death Comes as the End, 1945, another mystery set in Egypt taking place in 2000 B.C.E.

She first visited Egypt in 1910 as a debutante, and later set her first novel in Cairo titled Snow Upon the Desert but was unable to get it published. Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb aided her in her first published work, the short story, Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, in a weekly journal in 1928.

Max Mallowan, Agatha Christie, and Leonard Woolley.

While not a conventional archaeologist, Agatha Christie had a love and passion for the field. Upon an invitation from field director Leonard and his wife Katherine Woolley to the site of Ur in 1928, she took the Orient Express to the Iraqi capital before arriving at the Sumerian city of Ur and coming to understand the methods and awe of archaeology. She spent around 30 years of her life working and living in the East between 1928 and 1958, after meeting her second husband, archaeologist Max Mallowan who was 15 years her junior, at the site in 1930! They would spend fall and spring in the Middle East, summer in England with her daughter Rosalind, and then the rest of the year either traveling or at home. While working and scouting with her husband, she became an assistant, a field hand, and equipped with an understanding of archaeology which spilled into her books.

In 1933, the Mallowans took a Nile River cruise on their way to an archaeological dig which visited the cities of Luxor and Aswan, followed by another steamer the viewed Karnak and Ramses II’s Abu Simbel temples. After a return to Aswan a few years later and then coming back from the winter spent in Egypt, Death on the Nile was written.

Her earlier travels and duty as an archaeologist’s wife took her to Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Greece, Baghdad, Nejef, Kerbala, the site of Nippur, the site of Chagar Bazar, the site of Nimrud, the site of Tell Brak, and many more. Her duties and roles at sites increased as she put archaeology rather than writing first for a change but was still able to bankroll many of her husband’s expeditions through her writing as she spent mornings writing and afternoons completing site work. From 1935-1938 in the

Khabur valley in Syria at the site of Chagar Bazar, Christie would engage in kitchen work, put to use her nursing skills from past experience, supervise the running of meal preparation, collect potsherds, and photograph both the dig and artifacts recovered. Work carried into a second field season in 1936 as they branched into the site of Tell Brak and even into a third until WWII broke out and excavations were halted. The site of Chagar Bazar yielded around 70 cuneiform tablets with insight into the ethnic backgrounds of the former residents of the burned-out palace, and at Tell Brak, the well-known Eye Temple was present. While her husband aided the Air Ministry in Cairo with his knowledge of Arabic during the war, Christie remained in England and published Come, Tell Me How You Live in 1946, a memoir that described her and her husband’s digs in Syria and Iraq.

Agatha Christie photographing an Assyrian ivory figure at Nimrud in Iraq.

At the site of Nimrud from 1949-1959, she began to collect and clean artifacts, even going so far as to use face cream to clean and polish ivory artifacts, a cold-cream wash, as it came to be called. Freed from the social constraints of the Victorian lifestyle, her simplistic tasks that included putting together puzzle-like potsherds, gave her a sense of peace and allowed her to revel in the way archaeology connects the past to the present. At the age of 68, she went on her last dig, which was at Nimrud, still married to Max.

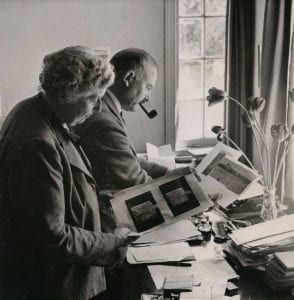

Agatha Christie and Max Mallowan in 1950.

Fictional detective Hercule Poirot states in Death on the Nile, “Once I went professionally to an archaeological expedition and I learnt something there. In the course of an excavation, when something comes out of the ground, everything is cleared away very carefully all around it. You take away the loose earth, and you scrape here and there with a knife until finally your object is there, all alone, ready to be drawn and photographed with no extraneous matter confusing it. That is what I have been seeking to do, clear away the extraneous matter so that we can see the truth, the naked shining truth.” Christie’s interest in archaeology was certainly connected to her love of mysteries. Archaeologists themselves are like detectives, using the left-behind clues of inscriptions or artifacts to decipher the mystery of the past. While Agatha Christie herself was never a recognized archaeologist, and to this day many do not even know about her prominent connections to archaeology, her writings are entrenched in her travels and adventures that inspired readers with her descriptions of ruins and the process of uncovering the past.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Further Reading:

Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists and Their Search for Adventure: By Amanda Adams