On April 5th, not only were students participating in Scholars Forum here at IUP, but we also invited students to our final Graduate Colloquium of the semester, which was a Virtual CRM Workshop. Hosted by The Eastern States Archaeological Federation Student Engagement Committee, Dr. David Leslie invited students and early career archaeologists to a presentation on applying for jobs in cultural resource management (CRM). Dr. Leslie is the Director of Archaeological Research and a Principal Investigator for Heritage Consultants, LLC in Connecticut. His goal of his presentation on Building a Career in Cultural Resource Management in Archaeology, was to provide useful advice on getting started in this growing field and provide students with more knowledge on how to advance their careers in archaeology.

The presentation began with an overview of CRM before discussing career paths. Over 90% of the archaeology that occurs in the United States is completed in a CRM setting; CRM is generally done at a faster pace than academic archaeology. There are three phases of excavation in CRM archaeology, Phase I, II, and III, but there can be many exceptions to this tradition structure. When a survey first takes place, they happen in conjunction with participating stakeholders. Stakeholders can include Federal and State recognized Native American Indian tribes, Federal Agencies, SHPO (State Historic Preservation Officer) offices, property owners, historical societies, the general public, and more. Coordination with all potential stakeholders is required both before and during each phase of the project.

During a Phase IA Survey, site identification is the main objective. It involves an assessment of a project area typically involving a bureaucratic organization (SHPO), archaeologists in CRM, and/or municipal offices, in order to identify if a parcel is archaeology sensitive. Besides excavating, soil coring is also another way to do a Phase I survey. In a Phase IB survey, one determines if an archaeological site is present within a project area, which is generally done through shovel test pit (STPs) surveys; and the presenter noted that the best surveys are done using a systematic grid survey at this stage, with judgmentally placed STPs as well. These intervals vary but are generally between 15 and 7.5 meters depending on the sensitivity and project size. The Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. is also in feet, with intervals between 50 and 25 feet. The presenter then described Phase II surveys. They noted that during this phase, the goal is to try to determine the spatial boundaries of the site within the project area, which includes the horizontal and vertical stratigraphy of the site. To test the site at higher intervals, additional STPs, at around 5 m or 16 ft intervals, are opened, and selected excavation units (EUs) are opened, around 1×1 m or 5×5 ft in the Mid-Atlantic region. Geophysical assessments of the sites are also conducted. During the Phase II process the site will be assessed for significance at the federal, state, and local levels, which vary in their specific criteria. During the Phase III process, if the site is eligible for the National Register, or some other state or local preservation, it must be avoided by development, or the effects of the development must be mitigated. Avoidance is preferred, but not generally prudent or feasible, as infrastructure projects may outweigh preservation in place or resources. Mitigation for archaeology generally involves excavation of a site and specialized analyses of the material record. Because most sites are Eligible for the National register under Criteria D (research potential), mitigation is most common as a Data Recovery Program (DPR), typically as widescale excavations. The percentage of the site excavated may differ depending on the data recovery efforts. However, while rate, it could in clue up to 100% of the site within the project area, but more generally, anywhere between 3%-5% of the site, if a large project area, or 20-30%, if a small project area, are excavated. Sometimes DPRs include partnering with academic or for-profit labs, depending on site type, importance, funding sources, etc. Some examples include, expanding documentary or deed research, microscopic use-wear analysis, protein residue analysis, radiocarbon or OSL dating, geochemical analysis, and more. You can find published examples of DPRs in academic journals, at presentations at conferences, at public presentation, in public booklets and websites, etc. The presentation then focused on other CRM projects and tasks that can be undertaken including burial ground investigations, using GPR/Magnetometer/Resistivity/UAV, conducing architectural history assessments, battlefield surveys, and metal detecting surveys, as well.

During a Phase IA Survey, site identification is the main objective. It involves an assessment of a project area typically involving a bureaucratic organization (SHPO), archaeologists in CRM, and/or municipal offices, in order to identify if a parcel is archaeology sensitive. Besides excavating, soil coring is also another way to do a Phase I survey. In a Phase IB survey, one determines if an archaeological site is present within a project area, which is generally done through shovel test pit (STPs) surveys; and the presenter noted that the best surveys are done using a systematic grid survey at this stage, with judgmentally placed STPs as well. These intervals vary but are generally between 15 and 7.5 meters depending on the sensitivity and project size. The Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. is also in feet, with intervals between 50 and 25 feet. The presenter then described Phase II surveys. They noted that during this phase, the goal is to try to determine the spatial boundaries of the site within the project area, which includes the horizontal and vertical stratigraphy of the site. To test the site at higher intervals, additional STPs, at around 5 m or 16 ft intervals, are opened, and selected excavation units (EUs) are opened, around 1×1 m or 5×5 ft in the Mid-Atlantic region. Geophysical assessments of the sites are also conducted. During the Phase II process the site will be assessed for significance at the federal, state, and local levels, which vary in their specific criteria. During the Phase III process, if the site is eligible for the National Register, or some other state or local preservation, it must be avoided by development, or the effects of the development must be mitigated. Avoidance is preferred, but not generally prudent or feasible, as infrastructure projects may outweigh preservation in place or resources. Mitigation for archaeology generally involves excavation of a site and specialized analyses of the material record. Because most sites are Eligible for the National register under Criteria D (research potential), mitigation is most common as a Data Recovery Program (DPR), typically as widescale excavations. The percentage of the site excavated may differ depending on the data recovery efforts. However, while rate, it could in clue up to 100% of the site within the project area, but more generally, anywhere between 3%-5% of the site, if a large project area, or 20-30%, if a small project area, are excavated. Sometimes DPRs include partnering with academic or for-profit labs, depending on site type, importance, funding sources, etc. Some examples include, expanding documentary or deed research, microscopic use-wear analysis, protein residue analysis, radiocarbon or OSL dating, geochemical analysis, and more. You can find published examples of DPRs in academic journals, at presentations at conferences, at public presentation, in public booklets and websites, etc. The presentation then focused on other CRM projects and tasks that can be undertaken including burial ground investigations, using GPR/Magnetometer/Resistivity/UAV, conducing architectural history assessments, battlefield surveys, and metal detecting surveys, as well.

Careers in CRM where then discussed. It was explained that most undergrads or graduate students without field experience start out as field technicians. To beef up ones resume or experience they can volunteer locally or seek out CRM firm internships. Starting out as a field technician though does provide a good, grounded perspective on field data collection, the speed of surveys, and the comradery of archaeological field crews. Basically, everyone starts out at this level. Field technicians are generally those with an undergraduate degree in anthropology or archaeology, or some related field. They need to have successfully completed and archaeological field school, local ones versus ones abroad are generally preferred by CRM companies. Most of the training as a field tech will be specific to paperwork, field techniques, and more, which will vary from company to company. The presenters commented that there are many different ways to conduct good archaeology, but these can vary between academic field schools and places you have previously worked at. While an M.A. in archaeology is certainly valuable and can aid you in a career in CRM, the presenters noted that you should not expect a supervisory position without commensurate (to the supervisory position) field experience in CRM. A field director leads a group of field technicians, ensures that the job is completed on schedule, lays out STPs and EUs for and with the crew, manages the crew in the field, conducts quality control of the excavation techniques applied by the crew, ensures that the paperwork is accurate and complete, and often has two or three years of field experiences (which is typically required as well). A project archaeologist manages several field projects, may visit sites and lead field crews, can spend more time in the field for complicated surveys (Phase II and III), writes portions or entire technical reports, conducts data analyses depending on their skill set (e.g., lithic analysis, zooarchaeological, spatial), typically needs to have several years of experience under their belt, and generally an M.A. is required.

The presentation then turned to careers in CRM. Certain skills are required, and depending on the course that you take or have access to, you can become specialized in a range of fields that align and enhance your CRM work. Training in and experience with GIS, total station or UAV surveys, human osteology, zooarchaeology, lithics analysis, historical deeds, mapping, or documentary research, geology, sedimentology, ceramic analyses, collections based work, soil flotation, artifact identification, artifact conservation, public history, art and architectural history, and more, are all skills and knowledge that would be useful to have a background in before entering a career in CRM. While many of these analyses are specialized, there may be departments or classes you can take to learn some of these skills during you time in undergrad and grad school. The presenters suggested that in undergrad you should think about minoring in GIS, geodesy (survey), geology, history, geography, remote sensing, biology, chemistry, and/or environmental studies. In grad school, they suggested that students focus on coursework in any of these fields as well.

The presenters also made suggestions for creating an appealing resume for CRM firms. They suggest that you play to your strengths, emphasize your field schools, archaeological experiences, and other related skills. You should denote your education level, list professional memberships, put in other previous jobs if light on archaeological fieldwork, and include any archaeo-specific computer programs you have experience with (e.g., artifact database intry, ArcGIS, Surfer, Metashape). They noted that it is ok if you resume is only one or two pages long at this stage, and that you should not include basic computer skills on your resume, as it is assumed that people should have these (classist, but a requirement for the job, as well).

The presenters claim that there has never been a better time to be employed in CRM, than now. They predict that the gross annual domestic spending on CRM from 2022-2031 is expected to rise from $1.46 to $1.85 billion. It is also expected that there is to be more than 11,000 jobs in CRM created in the upcoming decade, of which around 8,000 will be archaeologists. There is currently a job shortage in CRM at all stages, field technicians, crew chiefs, project archaeologists, and project managers, which has resulted in wage increases across all jobs. Field technicians in the Northeast five years ago were paid $15-16 an hour and can now expect $18-$22 depending on their experience. Per diem rates ($40-$50 per day) and mileage reimbursements are now more standard, and there are potentially higher rates in other parts of the country too. With an example position of a field tech with a B.A. and limited experience, they were expected to make around ~48K per year, from their hourly wage, per diem, and milage. Rates will continue to increase during the job crunch, and field directors and project archaeologists can expect an hourly rate of $23 or potentially higher, depending on experience.

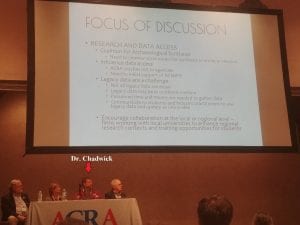

The Zoom presentation was then opened discussion, with Heritage Consultants stating that they were hiring for field technician positions at around $18-22 an hour, and $45 a day per diem & milage. There is also another Zoom call on April 26th by the White Mountain National Forest via the New Hampshire Archaeology Society, which will discuss opportunities in archaeology centered on the different aspects of positions within federal agencies. It was a great presentation, informative and educational, and perfect for someone who needed either a refresher on CRM or just a basic overview!

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram