This month of March is National Women’s History Month! There have been and continue to be inspiring female archaeologists that have contributed much to our understanding of history, archaeology, and the world around us! While there are many historical female archaeologists, we also seek to highlight and honor some of those within our IUP walls today that are contributing every day to our knowledge and interests about science, society, and the world.

Dr. Lara Homsey-Messer is a current IUP professor, and a geoarchaeologist with a MA in geology (2003) and PhD in archaeology (2004); both from the University of Pittsburg. After instructing and teaching at University of Pittsburg for several years, and then teaching at Murray State University in Kentucky for nine years, she began teaching at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in 2014. She teaches courses ranging from environmental archaeology and geoarchaeology, to the prehistory of North America. As an appointed Graduate Coordinator for the Applied Archaeology master’s program in 2017, she has guided students through intensive coursework and innovative thesis work. She has also contributed through her own studies and research, in journals such as the American Antiquity, Geoarchaeology, and Southeastern Archaeology. In 2019 she published Experiencing Archaeology: a Laboratory Manual of Classroom Activities, Demonstrations, and Mini-Labs for Introductory Archaeology. She is a Registered Professional Archaeologist (RPA), part of the Society for American Archaeology, and the Geological Society of America. During her time at IUP she has received the IUP President’s Recognition for Achievement in Scholarship three times (2015, 2016, & 2017). She also recently became a mother and is currently on a well-deserved sabbatical. Her work and efforts are a credit to all female archaeologists, and she deserves praise for all that she is contributing to our understanding of the past.

Dr. Andrea Palmiotto is also a current IUP professor, an archaeologist specializing in zooarchaeology, and a board-certified forensic anthropologist. She received her MA and PhD in anthropology from the University of Florida. She has worked for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, leading field recoveries in Vietnam and Laos to analyze and identify skeletal materials belonging to US casualties from WWII, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. She has recently led an IUP forensic archaeology field school in Frankfurt, Germany to recover a American WWII B-17 aircraft crash site. She also guides students through coursework including topics on human osteology, zooarchaeology, and forensic anthropology, to name a few. Her personal research has been published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Forensic Anthropology, Journal of Archaeological Science, Southeastern Archaeology, and more. She is an RPA, and a member of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, Society for American Archaeology, Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, and Southeastern Archaeology Conference, and she also serves as a technical assessor for the ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board. She recently received the highest professional certification through the American Board of Forensic Anthropology, making her one of two American Board of Forensic Anthropology Diplomates currently working in the state of Pennsylvania! She also led through 2021-2022 the formation of a digital textbook, or Open Educational Resource (OER), to be used in introductory anthropology courses; titled Introduction to Anthropology: Holistic and Applied Research on Being Human. She too has, and continues to, contribute valuable information to our knowledge about history, and is a woman deserving of recognition for all that she has accomplished.

There are many female archaeologists in the past that are now recognized as being trailblazers, some that did not get the recognition that they deserved during their time, and also many that are still alive today making incredible discoveries.

Dame Kathleen Kenyon (1906-1978) is a commonly referenced archaeologist who was the first female president of the Oxford University Archaeological Society. She developed the Wheeler-Kenyon grid method, to better understand soil layers. She became the leading English archaeologist of the Neolithic culture in the Fertile Crescent during her lifetime. Her work at Jerusalem and Jericho (excavated Tell es-Sultan 1952-1958) led to the knowledge that the ancient site of Jericho was the oldest continuously occupied settlement in history, the oldest and lowest town in the world. She served as director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and later as the principal of St. Hugh’s College at Oxford until she retired in 1973. Being in a different county other than Britain, she was able to move into positions of power, albeit through imperial links, but still positions of authority that she would most likely not have been able to occupy in the UK as a woman, giving her the opportunity to excavate new sites and contribute to history as an impressive and defining female archaeologist that led the way for more to come.

Jane Dieulafoy (1851-1916) was a French archaeologist, writer, and explorer, known for excavating the site of Susa along with her husband, in the late 1800s. She fought in the Franco-Prussian War, later traveling through Persia to Susa dressed in men’s clothes (trousers were illegal for women to wear in France during that time) with her hair cut short. She labeled, mapped, photographed, and reconstructed remains and finds, all new field recording methods for their time.

American archaeologist and anthropologist Zelia Maria Magdalena Nuttall (1857-1933) was the first to identify artifacts that dated back to the pre-Aztec period, as she specialized in pre-Aztec Mexican cultures and pre-Columbian manuscripts. She even recovered two manuscripts that were housed in private collections, essentially lost to the scientific world, one being the Codex Zouche-Nuttall.

Mary Brodrick (1858-1933) was a French woman who was initially turned away by male scholars at the Sorbonne in Paris, before she found there were no rules against studying archaeology; she became the first female student to be admitted to the prestigious institution. She became one of the first female excavators in Egypt.

Despite many barriers Maud Cunnington (1869-1951) faced as a female, such as not being able to legally own land as a married woman, she was eventually recognized for her contributions to archaeology. Along with her husband Ben Cunnington, she excavated the Neolithic burial mound at Woodhenge from 1926-1929, eventually purchasing and gifting Woodhenge and The Sanctuary (a Neolithic structure near Avebury) to the British nation. They even raised money to buy Stonehenge and the surrounding land for future public ownership. She was the first female president of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, the second women ever to be nominated as an honorary fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and she was distinguished as a Commander of the British Empire (CBE) in 1948.

Margaret Murray (1863-1963) is also a well-recognized female archaeologist of the early 20th century. She was the first female lecturer of archaeology in the U.K., teaching at the University College London. She specialized in Egyptology and excavated in Malta, Menorca, and even Palestine.

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926), also known as the “Mother of Mesopotamian Archaeology,” was the second woman to graduate from Oxford University in the U.K. She traveled to many archaeological sites in the Middle East, along with T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), becoming one of Europe’s foremost experts on Arab culture while she was alive, while also leading digs in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey. She was also the Director of Antiquities in Iraq, founding the Iraq Archaeological Museum in Baghdad in 1926.

Harriet Boyd Hawes (1871-1945) traveled to Crete and discovered, among many other sites, Gournia, the first Minoan settlement ever unearthed. Not only did she supervise around a hundred working men and women alike, but she was also able to publish her findings in a report still referenced today.

Dorothea Bate (1878-1951) was the first women employed as a scientist by the Natural History Museum of London; cataloguing collections until she was publishing her own scientific articles and work, all while traveling the world looking for fossils. She not only discovered many new species and fossils, but she paved the way for future researchers to better identify their own paleontological discoveries.

Born in Crete, Anna Apostolaki (1881-1958) was the first woman to be a member of the Archaeological Society of Athens, one of the first female graduates from the University of Athens, and the first curator of the National Museum of Decorative Arts in 1926, where she published a catalogue on Coptic textiles. A woman with power in the age of men, she was also the founder of the Lyceum Club of Greek Women.

Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888-1985) worked at sites in Egypt, Malta, Zimbabwe, and South Arabia. Her 1929 Zimbabwe dig was entirely excavated by women! She methodically excavated in 10×30 ft intervals and was the first archaeologist to use aerial surveys of the land to locate sites; these are methods still used today, essentially revolutionizing the way sites were studied and surveyed.

Dorothy Garrod (1892-1968) was the first female professor at Cambridge and led excavations at 23 sites throughout seven countries. Her work uncovered the first evidence of the Middle Stone Age and the first evidence of dog domestication. She led an incredible all-female excavation team at Mount Carmel that discovered the Tabun Neanderthal fossils. Another female of note that was active in this excavation was Yusra, a local Palestinian village woman, who actually pulled the single tooth from a sieve that led to the identification of Tabun 1. Yusra has now been credited by the Smithsonian for her find!

Tessa Verney Wheeler (1893-1936) was a British archaeologist, who along with her husband, Mortimer Wheeler, led excavations, such as the at the Iron Age hill fort at Maiden Castle, at which she was instrumental in gathering funding from the public due to her advocacy work. Wheeler and her husband were some of the first to film of their excavations to bring them to the public. She instructed many other female archaeologists on excavation techniques, her scientific approach to archaeology, and the recordation of small finds; these include Kathleen Kenyon, Beatrice de Cardi, Veronica Seton-Williams, Ione Gedye, Molly Cotton, and Egyptologist Margaret Drower. She also aided in the development of the Institute of Archaeology in London.

German mathematician Maria Reiche (1903-1998) studied the Nazca Lines of Peru in 1940, showed their mathematical accuracy, and suggested that they were related to astronomy. This brought more attention to these ancient areas, and by demonstrating their significance it aided in their preservation and protection.

Lady Aileen Fox (1907-2005) was one of the first female lecturers in archaeology, working at University College of the Southwest at Exter. The Richborough Roman Fort was the site of her first excavation, where she later developed a small museum on the site without training, as during her time there was little training available on how to do so. While struggling to create a new archaeology department at the University, Fox fought to show the world the value of archaeology, and all it has to offer.

Russian Tatiana Proskouriakoff (1909-1985) was an architect-turned-Mayan architecture and hieroglyphic interpreter. She produced reconstructions of Mayan architecture through plans and drawings. She was also the first to suggest that Mayan hieroglyphs contained dynastic histories, as well as calendrical information, which led to the decipherment of many hieroglyphs.

Jacquetta Hawkes (1910-1996) was focused on pioneering public archaeology, after digging in England, Ireland, and even Palestine. Her approach to interpreting archaeological evidence was more humanistic, leading to her suggestion that the Minoan society could have been ruled by women. She applied public archaeology techniques, spreading her theory by using newspapers, books, TV interviews, and even through the radio.

North American archaeologist Hannah Marie Wormington (1914-1994) was the second woman admitted by Harvard University’s anthropology department, and by the age of 24 she began publishing her textbooks, one of which, the Ancient Man in North America, was the standard on the subject for quite some time. She excavated sites and rock shelters across Colorado and Utah. She was also the first curator of archaeology at what is now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Cynthia Irwin-Williams (1936-1990) was a protégé of Wormington’s; she led the first archaeological excavations of the Valesquillo Reservoir area in Mexico. She also led projects in Nevada, Wyoming, New Mexico, and more.

Honor Frost (1917-2010) was a leading female in the underwater archaeology world. She applied her diving skills to expand excavations and reconstructions of submerged shipwrecks. After training under Kathleen Kenyon in Jericho she worked at sites in Lebanon, then later led dives and excavations of sites and shipwrecks in the Mediterranean. Her discoveries include the lost palace of Alexander and Ptolemy in the Port of Alexandria.

Lithuanian Marija Gimbutas (1921-1994) became a professor of Archaeology at University of California after her family emigrated. Maria studied female figurines, and the Baltic Neolithic and Bronze societies, and also developed the ‘Kurgan hypothesis’ (an Indo-European region migration hypothesis). She wrote three books focused on the civilization of goddesses of ‘old Europe,’ and while some of her ideas have been challenged, her interpretive work on material culture, social organization, and religious practices have led to new research and approaches.

Gudrun Corvinus (1932-2006) was not only an archaeologist, but also a paleontologist and geologist, excavating sites throughout Africa and Asia, contributing to both vertebrate paleontology and Paleolithic archaeology. She was part of the team that discovered the 3.2 million years old Australopithecus afarensis “Lucy” skeleton. While working in Ethiopia in 1974, she was the first person to find the Gona archaeological deposits, which included the oldest known stone artefacts in the world.

Another female archaeologist that not much is known about, but should be, is Gussie White, one of many African American women digging and laboring at the Irene Mound project in Georgia in 1937. Gussie spoke Gullah, and she even attended the Tuskeegee Normal School for women, which trained her as an educator and clerical worker, before the mound project. As an African American and a woman, she was not given the credit she deserved for her efforts and under the Works Progress Administration, she was paid little for her work (around 12 dollars a week). Today, her and others are beginning to be recognized for their contributions to history. Her efforts and those of other female African Americans will be remembered.

All of these women have made priceless contributions to the world of archaeology, and their names deserve to be known and recognized. Along with our IUP professors, there are other female archaeologists from many corners of the globe, working hard to continue to pave the way for anyone to become an archaeologist and find their place in the world of archaeology.

All of these women have made priceless contributions to the world of archaeology, and their names deserve to be known and recognized. Along with our IUP professors, there are other female archaeologists from many corners of the globe, working hard to continue to pave the way for anyone to become an archaeologist and find their place in the world of archaeology.

Shahina Farid was born in London to parents who emigrated from Pakistan. After studying archaeology at the University of Liverpool, she worked at sites in Turkey, Bahrain, London, and the United Arab Emirates, publishing over 40 scientific articles. She was also field director of the Çatalhöyük project for around twenty years, instructing and managing over 200 scientists, students, and volunteers from around the world at the 7,500 B.C. to 5,700 B.C. Neolithic and Chalcolithic settlement in Anatolia.

Dr. Alicia Odewale is an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Tulsa, focusing on archaeology of the African Diaspora in the Caribbean and Southeastern United States. A member of the Society of Black Archaeologists, her work focuses on community-oriented, Black feminist archaeology. She has worked on sites in St. Croix of the Virgin Islands, researching archaeological sites related to Afro-Caribbean heritage, but she has also researched sites in Oklahoma, Virginia, Arkansas, and Mississippi. She also serves as a co-creator of the Estate Little Princess Archaeological Field School that instructs local students on archeological skills, and as director of the Historical Archaeology and Heritage Studies Laboratory at TU.

Swedish-Somali archaeologist Dr. Sada Mire has a PhD from UCL’s Institute of Archaeology. She is the founder and executive director of the Horn Heritage Organization and is currently an assistant professor of archaeology at Leiden University. Her 2014 TEDxEuston talk focused on the need for cultural heritage. She has recently been active in the Horn of Africa, working to preserve its heritage by establishing the Department of Tourism and Archaeology in Somaliland, creating a digital museum that features Somali cultural materials and objects, and by teaching archaeological method to the local African people so they can carry out their own work.

Dame Rosemary Cramp was born in 1929 and is still alive today. She was the first female professor for Durham University, leading a team that excavated Jarrow Abbey, the home of Saint Bede, which recovered some of the earliest stained glass in Britain. She is currently working on the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, a research project seeking to document early sculptures in a systematic manner across the whole of England; the Corpus stands as the only existing record for several pieces of art. She was one of the first Trustees of the British Museum and one of the first Commissioners for English Heritage.

Kathleen O’Neal Gear is both an American archaeologist and well-known writer. She is a former state historian and archaeologist for Wyoming, Kansas, and Nebraska. She has received two Special Achievement Awards from the U.S. Department of the Interior for her work in archaeology, as well as a Spur Award for Best Historical Novel of the West. She has also received the Certificate of Special Congressional Recognition from the U.S. Congress, an Owen Wister Award for western literature, and she was even inducted into the Western Writers Hall of Fame.

Susan Greaney, a Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries (FSA), is a British archaeologist focusing on the study of British prehistory. She is a Senior Properties Historian with English Heritage. In 2019 she was named a BBC New Generation Thinker and she was also elected as a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London. She has conducted archaeological research and content development for sites such as Stonehenge, Tintagel Castle, and Chysauster ancient village.

Theresa Singleton is an African American archaeologist who focuses on the African Diaspora in, and historical archaeology of, North America. She was the first African American recipient of the Society of Historical Archaeology’s highest honor, the J.C. Harrington Award. She is currently an author and associate professor at Syracuse University, teaching anthropology and historical archaeology.

American classical archaeologist Joan Breton Connelly is a professor of Classics and Art History at New York University. She is also currently the director of the Yeronisos Island Excavations and Field School in Cyprus, and she is even an honorary citizen of the Municipality of Peyia, Republic of Cyprus. She received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1996, the Archaeological Institute of America Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching Award in 2007, and the Lillian Vernon Chair for Teaching Excellence at NYU from 2002-2004.

Archaeologist and Egyptologist Sarah Parcak uses remote sensing and satellite imaging to focus on locating potential sites in Rome, Egypt, and other areas formerly occupied by the Roman Empire. While working as a professor of Anthropology and director of the Laboratory for Global Observation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, she also works with her husband to direct projects in the Sinai, Faiyum, and Egypt’s East Delta.

There have been many incredible female archaeologists, and more continue to work hard and inspire the next generation even today. A great resource for more information on female archaeologists is the TrowelBlazer organization, https://trowelblazers.com, which shares the contributions of women and other underrepresented groups studying archaeology, geology, and paleontology, and also provides resources for them. This month, remember those who overcame incredible odds, faced many obstacles, and challenged adversity, all in their pursuit for historical truths, recognition, and especially for their passion of archaeology.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

References:

https://www.europeana.eu/en/blog/groundbreaking-women-in-archaeology

https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/first-female-archaeologists/

https://ulasnews.com/2021/03/08/women-in-archaeology/ndigventures.com/2015/03/pioneering-women-in-archaeology/

https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/pioneering-female-archaeologists/

https://www.history.co.uk/articles/the-most-inspirational-female-archaeologists-from-history

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/women-in-history/six-groundbreaking-female-archaeologists/

https://www.ranker.com/list/famous-female-archaeologists/reference

https://www.livescience.com/62086-pioneering-women-archaeologists.html

During a Phase IA Survey, site identification is the main objective. It involves an assessment of a project area typically involving a bureaucratic organization (SHPO), archaeologists in CRM, and/or municipal offices, in order to identify if a parcel is archaeology sensitive. Besides excavating, soil coring is also another way to do a Phase I survey. In a Phase IB survey, one determines if an archaeological site is present within a project area, which is generally done through shovel test pit (STPs) surveys; and the presenter noted that the best surveys are done using a systematic grid survey at this stage, with judgmentally placed STPs as well. These intervals vary but are generally between 15 and 7.5 meters depending on the sensitivity and project size. The Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. is also in feet, with intervals between 50 and 25 feet. The presenter then described Phase II surveys. They noted that during this phase, the goal is to try to determine the spatial boundaries of the site within the project area, which includes the horizontal and vertical stratigraphy of the site. To test the site at higher intervals, additional STPs, at around 5 m or 16 ft intervals, are opened, and selected excavation units (EUs) are opened, around 1×1 m or 5×5 ft in the Mid-Atlantic region. Geophysical assessments of the sites are also conducted. During the Phase II process the site will be assessed for significance at the federal, state, and local levels, which vary in their specific criteria. During the Phase III process, if the site is eligible for the National Register, or some other state or local preservation, it must be avoided by development, or the effects of the development must be mitigated. Avoidance is preferred, but not generally prudent or feasible, as infrastructure projects may outweigh preservation in place or resources. Mitigation for archaeology generally involves excavation of a site and specialized analyses of the material record. Because most sites are Eligible for the National register under Criteria D (research potential), mitigation is most common as a Data Recovery Program (DPR), typically as widescale excavations. The percentage of the site excavated may differ depending on the data recovery efforts. However, while rate, it could in clue up to 100% of the site within the project area, but more generally, anywhere between 3%-5% of the site, if a large project area, or 20-30%, if a small project area, are excavated. Sometimes DPRs include partnering with academic or for-profit labs, depending on site type, importance, funding sources, etc. Some examples include, expanding documentary or deed research, microscopic use-wear analysis, protein residue analysis, radiocarbon or OSL dating, geochemical analysis, and more. You can find published examples of DPRs in academic journals, at presentations at conferences, at public presentation, in public booklets and websites, etc. The presentation then focused on other CRM projects and tasks that can be undertaken including burial ground investigations, using GPR/Magnetometer/Resistivity/UAV, conducing architectural history assessments, battlefield surveys, and metal detecting surveys, as well.

During a Phase IA Survey, site identification is the main objective. It involves an assessment of a project area typically involving a bureaucratic organization (SHPO), archaeologists in CRM, and/or municipal offices, in order to identify if a parcel is archaeology sensitive. Besides excavating, soil coring is also another way to do a Phase I survey. In a Phase IB survey, one determines if an archaeological site is present within a project area, which is generally done through shovel test pit (STPs) surveys; and the presenter noted that the best surveys are done using a systematic grid survey at this stage, with judgmentally placed STPs as well. These intervals vary but are generally between 15 and 7.5 meters depending on the sensitivity and project size. The Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. is also in feet, with intervals between 50 and 25 feet. The presenter then described Phase II surveys. They noted that during this phase, the goal is to try to determine the spatial boundaries of the site within the project area, which includes the horizontal and vertical stratigraphy of the site. To test the site at higher intervals, additional STPs, at around 5 m or 16 ft intervals, are opened, and selected excavation units (EUs) are opened, around 1×1 m or 5×5 ft in the Mid-Atlantic region. Geophysical assessments of the sites are also conducted. During the Phase II process the site will be assessed for significance at the federal, state, and local levels, which vary in their specific criteria. During the Phase III process, if the site is eligible for the National Register, or some other state or local preservation, it must be avoided by development, or the effects of the development must be mitigated. Avoidance is preferred, but not generally prudent or feasible, as infrastructure projects may outweigh preservation in place or resources. Mitigation for archaeology generally involves excavation of a site and specialized analyses of the material record. Because most sites are Eligible for the National register under Criteria D (research potential), mitigation is most common as a Data Recovery Program (DPR), typically as widescale excavations. The percentage of the site excavated may differ depending on the data recovery efforts. However, while rate, it could in clue up to 100% of the site within the project area, but more generally, anywhere between 3%-5% of the site, if a large project area, or 20-30%, if a small project area, are excavated. Sometimes DPRs include partnering with academic or for-profit labs, depending on site type, importance, funding sources, etc. Some examples include, expanding documentary or deed research, microscopic use-wear analysis, protein residue analysis, radiocarbon or OSL dating, geochemical analysis, and more. You can find published examples of DPRs in academic journals, at presentations at conferences, at public presentation, in public booklets and websites, etc. The presentation then focused on other CRM projects and tasks that can be undertaken including burial ground investigations, using GPR/Magnetometer/Resistivity/UAV, conducing architectural history assessments, battlefield surveys, and metal detecting surveys, as well.

On November 2nd, Dr. Claire Milner, Emeritus Curator and Director of Exhibits at Penn State’s Matson Museum of Anthropology, joined us for her presentation, “Dating, Dumping, and Destruction: Reconstructing Life Histories of Farmers and Farmhouses in Central Pennsylvania.” She described three Penn State archaeological field schools she ran as project director at farmsteads in Central Pennsylvania. Two sites were excavated in Huntingdon County, the Massey site from 2006-2007 and the Scare Pond Farm from 2008-2009. She led excavations at the Foster site in Centre County from 2015-2016, as well.

On November 2nd, Dr. Claire Milner, Emeritus Curator and Director of Exhibits at Penn State’s Matson Museum of Anthropology, joined us for her presentation, “Dating, Dumping, and Destruction: Reconstructing Life Histories of Farmers and Farmhouses in Central Pennsylvania.” She described three Penn State archaeological field schools she ran as project director at farmsteads in Central Pennsylvania. Two sites were excavated in Huntingdon County, the Massey site from 2006-2007 and the Scare Pond Farm from 2008-2009. She led excavations at the Foster site in Centre County from 2015-2016, as well.

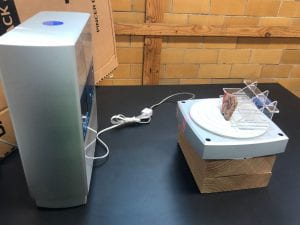

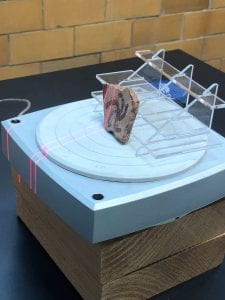

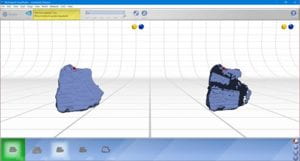

Dr. Chadwick, a professor here at IUP, were also in this room, discussing the PHAST (PennDOT Highway Archaeological Survey Team) program, what goes inside a dig kit, and what some of the geophysical tools used in archaeology are and how they operation. These such geophysical instruments included metal detectors and ground-penetrating radar.

Dr. Chadwick, a professor here at IUP, were also in this room, discussing the PHAST (PennDOT Highway Archaeological Survey Team) program, what goes inside a dig kit, and what some of the geophysical tools used in archaeology are and how they operation. These such geophysical instruments included metal detectors and ground-penetrating radar.