This is a special extension of Material Culture Monday featured on our Facebook Page.

Written by Dr. Lara Homsey-Messer

In 1974, the crew of the scallop trawler Cinmar were dredging off the coast of Virginia when, to everyone’s surprise, a mastodon skull was reeled in. Recognizing this as an unusual find, the Cinmar captain plotted the water depth and locational coordinates on his navigation charts. To expedite getting back to dredging, the Cinmar crew broke up the skull and removed the tusks and teeth for souvenirs, throwing the rest of the bone overboard. The mastodon was later radiometrically dated to 22,760 ± 90 Radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP), prior to the last glacial maximum (LGM). In addition to the

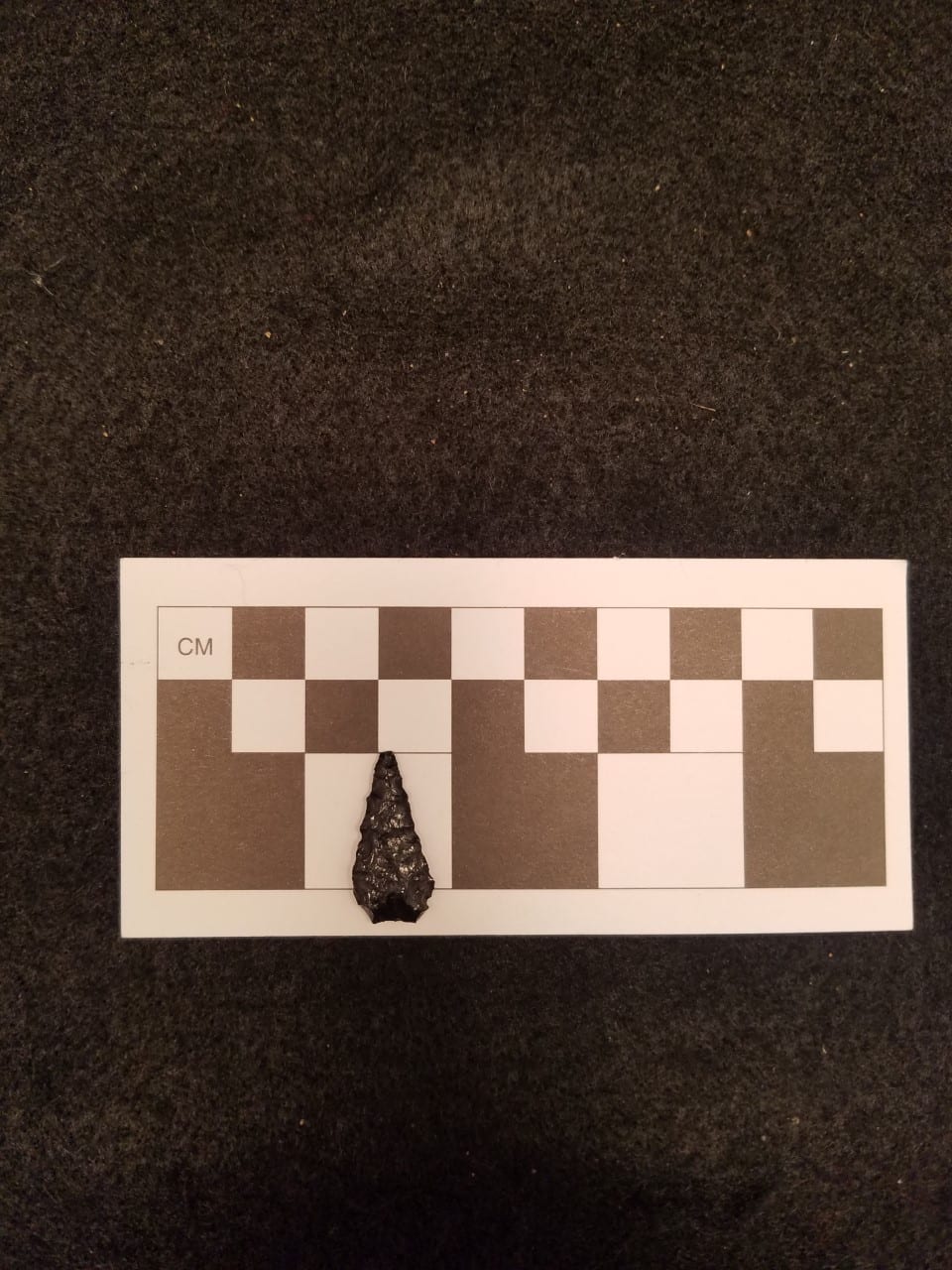

Photograph of the Cinmar Biface

mastodon fossil, a bifacially flaked tool was also recovered. Made out of a fine-grained volcanic rock called rhyolite, the so-called “Cinmar biface” is a large, thin knife with evidence of well-controlled percussion thinning flake scars on both faces. Because rhyolite is an extremely durable rock, it is very difficult to flake correctly. As the Cinmar biface is well-crafted, it clearly represents the workmanship of a highly skilled knapper. Several prominent archaeologists (including lithics expert Bruce Bradley, geologist Darrin Lowery, and the late Dennis Stanford of the Smithsonian Institute) have examined the biface and concluded that it bears a striking resemblance to the Solutrean “laurel leaf” biface tradition of southwestern Europe. As such, the Cinmar biface has been cited as evidence for a pre-LGM “Solutrean crossing” from Europe to the eastern coast of North America via the north Atlantic coastline. Proponents argue that at least 8 other laurel leaf bifaces can be firmly provenienced to the Chesapeake Bay region in addition to the Cinmar biface. You can read more about the biface here.

The Cin-Mar scallop trawler that found the skull and biface

Certainly, this is a tantalizing discovery, but it is not without its critics. Several problems have been noted by skeptics. First, the 22,760 RCYBP date is about 2,000 years before the appearance of Solutrean style bifaces in western Europe. Second, geochemical analysis of the biface, and hundreds of other rhyolite artifacts with known origins from Maine to the Carolinas, showed the rhyolite to originate from the Catoctin Mountain region of south-central Pennsylvania and north-central Maryland. Finally, we have only the word of the Cinmar crew that the biface and mastodon are associated; given that they were found during dredging, it is difficult—if not impossible—to confirm that they originate in the same deposit. This raises questions about the European origins, as well as the Solutrean peopling of the Americas hypothesis. You can read more about the skeptics’ response here.

But before we completely dismiss the Cinmar biface and the Solutrean hypothesis, we should remember that archaeology is all about testing hypotheses, and the Solutrean hypothesis is certainly testable. It will be up the next generation of archaeologists to delve more deeply into the origins and manufacture of laurel leaf style bifaces!

But before we completely dismiss the Cinmar biface and the Solutrean hypothesis, we should remember that archaeology is all about testing hypotheses, and the Solutrean hypothesis is certainly testable. It will be up the next generation of archaeologists to delve more deeply into the origins and manufacture of laurel leaf style bifaces!

Follow #MaterialCultureMonday on out Facebook