Archaeology has a strong presence in the news. It is rare that I don’t find some new discovery or article about relating to archaeology while scrolling through my Facebook news boards. Recently, some very interesting research has been released to the public.

The Crew of the Mary Rose

The Mary Rose is a ship build for Henry VIII King of

Image of the Mary Rose

Tudor England. It sank in 1545 while fighting the French and lost its crew of 400-600 sailors. Recent studies on the ancestry of the crew have discovered some very interesting things. Based on the 10 discovered skeletons, most of the crew were from the Mediterranean and Southern Europe. On member in particular, dubbed Henry, was found to be from Morocco or Algeria based on his skeletal features. Isotope analysis of his teeth indicated, however, that he was raised in Portsmouth. To read more about Henry and the Mary Rose so to BBC’s article here.

Archaeology is the….dog’s poop….

Recent research conducted on paleofeces discovered that many of the samples thought to be human were actually dog. Christina Warriner and her graduate student collected DNA samples from both human and dog poop and a variety of other elements that could end up in poop and created a program called coprolID which has the ability to differentiate between the samples. The increased amount of dog poop in the record may not shed too much light only human patterns but it has the potential to increase our knowledge of dog domestication. To read more check out the article in Science Magazine here.

A Feast of Sharks and Dolphins

For a long time fishing has bee n seen as a hallmark of modern humans. The earliest site of mass seafood consumption dates to 160,000 in southern Africa. New evidence indicates that Neanderthals in Figuera Brava in Portugal also consumed large amounts of seafood including sharks, dolphins, eels, shellfish, fish and a variety of other species some 106,000-86,000 years ago. Evidence shows that seafood consisted of 50% of these Neanderthals’ diets, a percentage similar to modern humans of the time. To read more see BBC’s article here.

Also follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

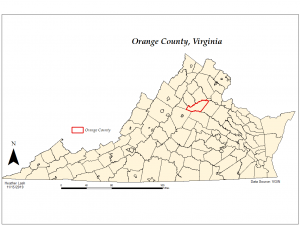

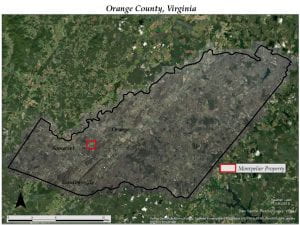

By focusing on the daily act of eating, and all processes involved in production and consumption of food, the agency of communities and individuals can be illuminated. Reconstructing food processes contributes to better understanding one aspect of daily life that introduces choice based on preference. In my thesis, “Foodways of Pre- and Post-Emancipation African Americans at James Madison’s Montpelier: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Food Preference and Food Access,” I explore African foodways through Zooarchaeological identification and analysis. By matching each bone to IUPs Zooarchaeological Comparative Collection, and determining the presence and absence of different animals in the collection, Trends describing preference of food and access to foodstuffs can be clearly differentiated. At James Madison’s house, Montpelier, located in Virginia, the need exists for pre- and post- emancipation subsistence practices to be contrasted, compared, and evaluated. Therefore, detailing differences and similarities between one group of enslaved individuals and one free family across the Montpelier property can also delineate post-Emancipation effects on food procurement and the utilization of foodstuffs.

By focusing on the daily act of eating, and all processes involved in production and consumption of food, the agency of communities and individuals can be illuminated. Reconstructing food processes contributes to better understanding one aspect of daily life that introduces choice based on preference. In my thesis, “Foodways of Pre- and Post-Emancipation African Americans at James Madison’s Montpelier: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Food Preference and Food Access,” I explore African foodways through Zooarchaeological identification and analysis. By matching each bone to IUPs Zooarchaeological Comparative Collection, and determining the presence and absence of different animals in the collection, Trends describing preference of food and access to foodstuffs can be clearly differentiated. At James Madison’s house, Montpelier, located in Virginia, the need exists for pre- and post- emancipation subsistence practices to be contrasted, compared, and evaluated. Therefore, detailing differences and similarities between one group of enslaved individuals and one free family across the Montpelier property can also delineate post-Emancipation effects on food procurement and the utilization of foodstuffs.

For the most part, they were treated and paid well, able to travel with their families, and able to retain their traditional ways of life. Despite these positive aspects of the show, they were still viewed as warlike savages preventing the expansion of civilization into the West. The Native American victory at Little Big Horn was even used to show audiences why westward expansion is needed. In the 1890s Buffalo Bill’s employed hundreds of Native Americans, vastly outnumbering the number of cowboys and cowgirls.

For the most part, they were treated and paid well, able to travel with their families, and able to retain their traditional ways of life. Despite these positive aspects of the show, they were still viewed as warlike savages preventing the expansion of civilization into the West. The Native American victory at Little Big Horn was even used to show audiences why westward expansion is needed. In the 1890s Buffalo Bill’s employed hundreds of Native Americans, vastly outnumbering the number of cowboys and cowgirls.