This past Wednesday we had our first Graduate Colloquium of the semester! IUP graduate students travel all over the country during summer breaks to participate in various archaeological projects which is why we wanted to feature their adventures in our first colloquium. There were 5 presentations in total whose topics ranged from field schools to cultural resource management work at sites around the country and abroad!

Zach Meskin, a member of the second-year cohort, gave the first presentation. He spent his summer working for the cultural resource management (CRM) firm SEARCH. At the beginning of the summer, he was sent to a sugar cane field in Louisiana where he conducted a phase one survey. They used 30×50-cm shovel test pits and either 10 to 50-meter intervals depending on if there was a high or low probability of finding cultural material. There ended up being 1,400 test pits placed throughout the field in total but in his shovel test pits, he did not find much cultural material.

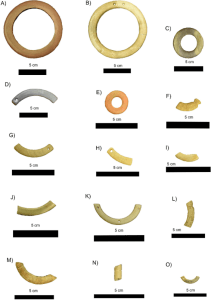

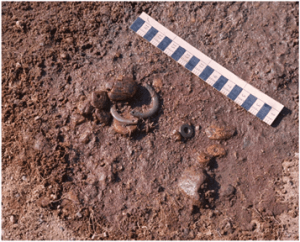

After Louisianna, Zach traveled to Miami, Florida where he worked on phase three of a pre-contact Tequesta site. This was a completely different experience since he worked in 4×4 meter blocks and wet screened the dirt because of the thickness of the mud. They found many different artifacts throughout the units including drilled shark teeth, finger-incised pottery, faunal remains, and shell tools. There was also a historic component to the site so they found Spanish artifacts including a six-sided die made out of bone.

Our second presenter Laura Broughton talks about her experience as a GA for IUP’s summer field school.

Our next presenter was Laura Broughton, a member of the first-year cohort. She worked as a graduate assistant for both IUP-run field schools this summer and this presentation was about Squirrel Hill. She was also joined by the disembodied voice of Emma Lashley, another member of the first-year cohort, who joined us over zoom. Squirrel hill is a pre-contact Monongahela village site located on the Conemaugh river. It has been nominated to the Historical Register and has a long history of collection and looting. Therefore, many of the artifacts found were flakes and small pieces of pottery.

The goal of the field school was to educate students on how to conduct an archaeological investigation and to get a better understanding of the organization of the site and how it fits into the larger Monongahela system in southwest PA. In one area of the site, they investigated a rectangular anomaly in the Ground Penetrating Radar data by placing four 1×1 meter test units. They did not find much but they think that it could be an Iroquois Longhouse. In another section, they investigated other geophysical anomalies and had much better success. Students found post molds that looked promising and more than 20 features in a singular unit which could indicate a bunch of housing structures in that area. Lastly, STPs were conducted to determine the extent of the site boundaries.

Next up was Kris “Monty” Montgomery who worked at both the Miami site that Zach worked on and was the other graduate assistant for the Squirrell Hill field school where he “shaped the next generation of archaeologists”. His words. After he worked at Squirrel Hill he went to work for SEARCH in Gonzales, Texas for a phase one “due diligence” survey that was paid for by the client and not required under any kind of compliance. The survey was limited to intermittent stream crossings. Interestingly, they did not collect artifacts and instead recorded and analyzed them in the field.

Then, at the end of July/ early August, he was sent to Macomb, Illinois, and Fort Madison, Iowa where he worked with two other firms to conduct phase one for a large natural gas pipeline. Finally, at the end of August, he worked at the Miami site that was mentioned above. During his time at the site, they hit the water table meaning they were less digging through dirt and more scooping goo and placing it into buckets.

Our fourth presenter Luke Nicosia talks about his summer as a crew chief for a field school in Virginia.

Our fourth presenter was Luke Nicosia, a member of the second-year cohort as well. He was recruited by Longwood University to work as a field supervisor in Clover, Virginia which is in the Southernmost part of the state. He lived at a field station while he was working down there which he equated to a summer camp cabin with no internet. However, the sites that he worked at made up for it. The first part of his summer included working at the Sanders site and opening large units to search for pre-contact materials. They found many projectile point knives and flakes.

The second site Luke worked on was a historical site at Milberry Hill where students worked on advanced research. They ground-truthed anomalies and identified a few features including a drainage system related to the main house, an outbuilding with a sub-floor pit that may have fallen apart over time, and potential pre-contact hearths. After the fieldwork, he worked with students to write a site report and submit it to the state to review.

Finally, we welcomed Laura Broughton back, this time with Arthur Townsend, to talk about their summer abroad working as GAs and crew chiefs for IUP’s forensic field school in Germany. They investigated a site around Buchen where a B-17 bomber crashed during WWII in 1944. There was already an excavation by another group in 2019 but they did not fill in their excavation causing there to be essentially a pond at the site. After this was dealt with, the IUP field school excavated in 2×2,2×4, and 4×4 meter units bordering the 2019 excavations and used ground penetrating radar to locate other places to dig around the area. Since the ground was rocky and had a lot of clay they used pickaxes and shovels to excavate. They also realized a lot of cultural material was in the leaf litter so they put it through the screen to ensure they were collecting all the artifacts. They mostly found bones, aluminum, cast iron, and glass. Both presenters said they learned a lot about how to lead a crew and improved their note-taking and photography skills.

As you can see, we had a great turnout. Thank you to everyone that presented!

Deaf History Month in the past has run from March 13th-April 15th, in honor of three momentous dates for the deaf community. These include; April 15th, 1817, when the first school for deaf students was opened, April 8, 1864, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the charter for Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. (the only university in the world where students live and learn using American Sign Language (ASL) and English), and in March 1988 Gallaudet appointed their first deaf president. Starting in 2022, Deaf History Month will now be held from April 1-30 based on feedback from the NAD Deaf Culture and History Section (DCHS), as well as from organizations representing marginalized communities within the Deaf Community.

Deaf History Month in the past has run from March 13th-April 15th, in honor of three momentous dates for the deaf community. These include; April 15th, 1817, when the first school for deaf students was opened, April 8, 1864, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the charter for Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. (the only university in the world where students live and learn using American Sign Language (ASL) and English), and in March 1988 Gallaudet appointed their first deaf president. Starting in 2022, Deaf History Month will now be held from April 1-30 based on feedback from the NAD Deaf Culture and History Section (DCHS), as well as from organizations representing marginalized communities within the Deaf Community.