By: Genevieve Everett

This semester we have been talking a lot about how to get the public involved/interested in archaeology and the preservation of cultural resources. Most importantly, how can we make what we do relevant to people outside of our field? We have read Jeremy Sabloff’s book, “Why Archaeology Matters”, which discusses the many ways in which archaeologists are contributing on a local, regional, national and global scale. According to Sabloff, as archaeologists we should be “working for living communities, not just in or near them”(Sabloff 2008:17). An excellent example of someone that is attempting to work with the public is ‘space archaeologist’, Sarah Parcak. Parcak’s new project, GlobalXplorer allows the public to get involved in the effort to combat looting of archaeological sites around the world.

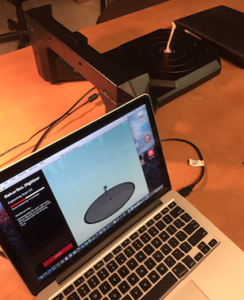

Sarah Parcak is an Egyptologist, and is best known for her work looking at satellite images to find archaeological sites and signs of looting. According to the website, “So far, Dr. Parcak’s techniques have helped locate 17 potential pyramids, in addition to 3,100 potential forgotten settlements and 1,000 potential lost tombs in Egypt — and she’s also made significant discoveries in the Viking world and Roman Empire.” (GlobalXplorer 2017). Check out the TED talk for which Parcak earned the 2016 TED prize of 1 million dollars. Parcak used her award to create GlobalXplorer as a way to train the public to spot looting on satellite images. I went to the website, and decided to sign up as a global explorer. Once signed up, there is a short tutorial video that explains what looting typically looks like when looking down on the earth from a satellite. Once the tutorial is done, a satellite image/tile is brought up, and based on what your learned in the tutorial, you must decide if this tile displays looting or not. It’s much harder than you think, because trees, bushes and mounds of dirt kind of look like looting pits; however, once you look at enough tiles you begin to recognize the pits versus the natural landscape. To date, over 44,000 people have signed up to look at the tiles, and over 9 million tiles have been explored so far!

The work that Parcak has done is incredible, and for an archaeologist like myself, I find this to be extremely fascinating, and an awesome platform for getting the public involved in a joint effort to protect cultural resources. People are drawn to research like Parcak’s, because it is innovative and interactive. Just spouting facts at people about why looting is bad is not enough; rather, giving people the knowledge and tools to combat looting makes them feel like they are making a contribution to something big. Parcak’s research seems to be bridging the gap between archaeologists and the public, creating a new generation of stewards. As more people get involved with this project, there is a better chance that archaeological sites will be protected from looting and destruction. I am really excited to see how GlobalXplorer progresses!