by Dr. Sarah Neusius

Next to excavation one of the most fun things for an archaeologist to do is go visit someone else’ site and look at their artifacts. Between June 2 and 5, Dr. Phil and I got to do just that when I co-led the 2016 Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology (SPA) field trip with Dr. John Nass of California University of Pennsylvania. This year we went to see the archaeology going on in Virginia at places like Mt Vernon, Montpelier, and Monticello with a group of 20 professional and avocational archaeologists.

We started in Bedford, PA where we had evening orientation which covered the estates we would be visiting and cool facts about the four early US Presidents’ who had homes in Virginia: Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. Then we loaded into vans and headed south to Virginia early Friday morning.

On Friday we battled DC traffic to get to Mount Vernon where we had a tour of the house and then a tour by Dr. Luke Pecoraro, Director of Archaeology. He took us around the grounds and included visits to the locations of several excavations as well as to the archaeology laboratory. One interesting thing is that grave locations at the current excavation of the slave cemetery are being exposed but not excavated, and regardless, the prehistoric artifacts that have been recovered indicate that there is a Late Archaic site at this same spot. We also learned that there are lots of student and volunteer opportunities to get involved with Mt. Vernon archaeology that we can share with IUP students.

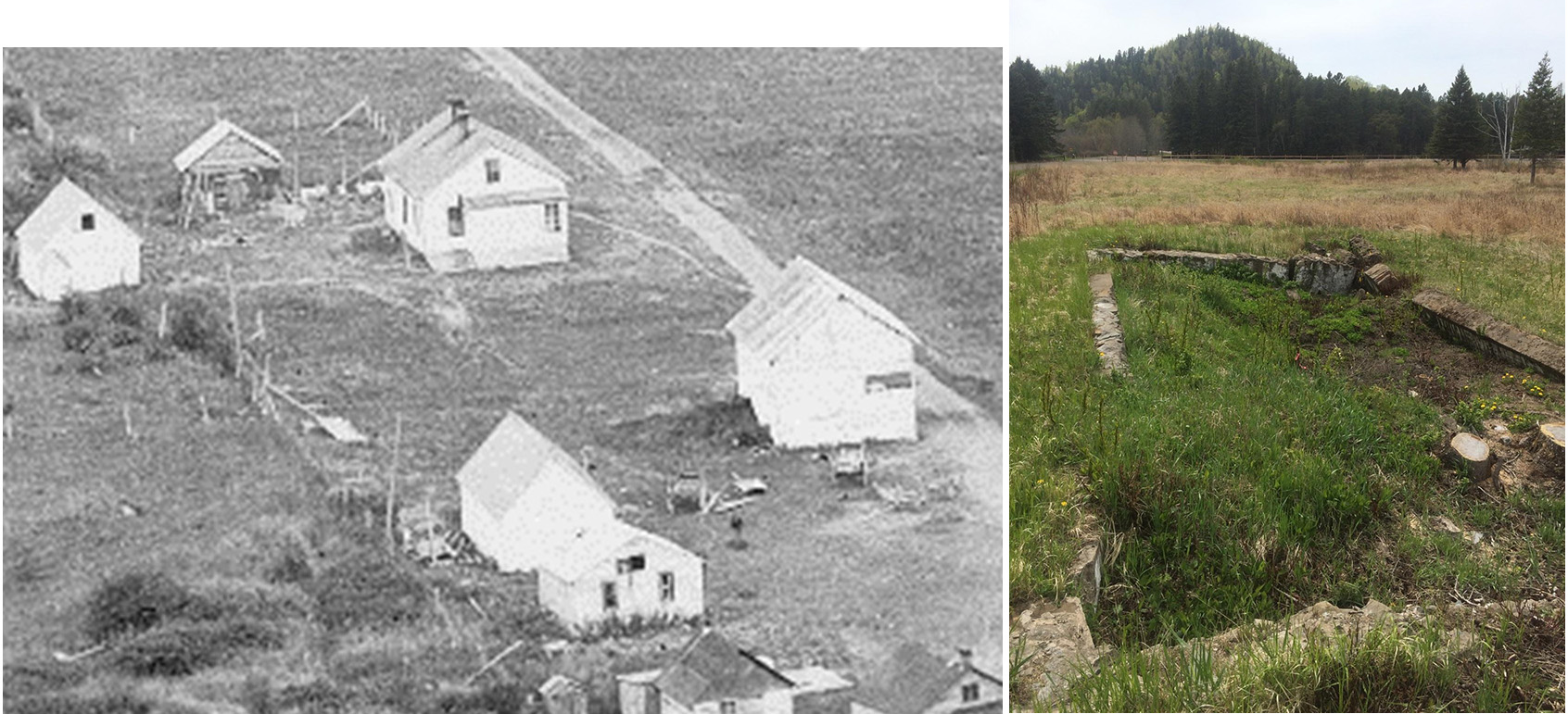

Later Friday afternoon we visited Washington’s boyhood home where archaeologists with the George Washington Foundation including Dr. Dave Muraca and Laura Galke gave us tours of the site and the lab. Unfortunately we got caught in a downpour while viewing the excavations and the foundations for the house now being reconstructed. However, the staff was very nice to let us drip into the lab anyway and look at some of the many artifacts (men’s wig curlers, a masonic pipe and much more!), which they have recovered because of their thorough excavations.

In the evening we had a lecture by Dr. Doug Owsley from the Smithsonian Institution who talked about his forensic studies of early burials found at St. Mary’s City and Jamestown. Though a century earlier than the rest of this field trip’s explorations, Dr. Owsley’s recent work on these burials is fascinating and cutting edge!

Friday pictures: Here I am on tour at Mt Vernon; Dr. Pecararo explaining findings at Mount Vernon’s South midden; Laura Galke discussing the many men’s wig curlers found at Ferry Farm.

On Saturday we had another packed day visiting Madison’s Montpelier before going to Jefferson’s home at Monticello, both of which are historic sites near Charlottesville. Madison may be less well known than other presidents, but our fourth President was a complicated man responsible for the division of our government into three branches, our leader in the War of 1812, and of course, husband to Dolley Madison. Together they may have been our nation’s first “power couple”! The archaeology at Montpelier, which we learned about from Stephanie Hallinan, Director of Public Archaeology, is also interesting. At the moment, Montpelier archaeologists are focusing on homes of the enslaved population, especially the domestic slaves and skilled craftsmen who were housed close to the Montpelier mansion.

We had so much fun at Montpelier that we were late getting to Monticello and had to switch our house tour to the end of the afternoon. This meant that Dr. Fraser Neiman, Director of Archaeology, took us on our landscape archaeology tour first. During this tour we hiked the hill at Monticello learning how the use of the land changed when the plantation switched from tobacco production to wheat farming and how this apparently affected the social relationships of everyone living there from owners to overseers to slaves. When it came time to tour the house, the guides actually made us take off our shoes, which were encrusted with Monticello’s red clay from our hike through the woods! So I can say I have been in Thomas Jefferson’s home barefoot!

Saturday evening we heard a lecture by Kyle Edwards, UVA Ph.D. student who is doing his dissertation on Monroe’s home at Highland, which is also near Charlotte. The most recent development is that new archaeological work there shows Monroe did have a substantial house at Highland. Even though the interpretation for many years has been that he only had a small, cabin-sized house, that structure is now believed to have been a guest house. Archaeology has debunked another historical myth!

Saturday pictures: Stephanie Hallinan explaining the excavations and slave cabin reconstructions underway at Montpelier; Our group approaching the house at Montpelier; Dr. Neiman (far right) explaining the excavations Monticello Archaeology has been doing in the woods downslope from the house at Monticello.

Sunday was our last day, but we drove south again so as not to miss Jefferson’s retreat at Poplar Forest. One of the interesting things about Poplar Forest is that the reconstruction, which has been heavily driven by archaeology, is still underway so one can really see how the staff is working to reconstruct this place accurately. The house tour was full of stories about people like the master craftsman, a slave, who made the friezes and other trim to Jefferson’s specifications. Then, Dr. Jack Gary, Director of Archaeology led us on a tour explaining how they are reconstructing the landscape using archaeology to find details like the spacing of ornamental trees. I hadn’t thought the reconstructing a landscape could be so fascinating, but it was another testament to what we can learn from modern archaeology. Beside that Poplar Forest is a special place, still remote and relatively unknown, which everyone interested in archaeology, historic preservation, and/or Jefferson should visit.

After Poplar Forest we had a long ride back to Bedford before dispersing in the evening for our various homes, but this gave us lots of time to debrief and talk about our experiences. It was another great SPA field trip! Keep in mind that the SPA will be doing similar trips early each June and you might like to join us on one. You might even consider joining the SPA in order to take advantage of this and other member benefits which include the Pennsylvania Archaeologist, one of the longest running state archaeology journals in the country. At just $18 for students and $25 for non-students or $30 for families, membership is a great bargain. For details on joining see www.pennsylvaniaarchaeology.com). Then stay tuned for word on plans for another memorable trip next June!

Sunday pictures: Dr. Gary giving the archaeology tour to our group including Dr. Phil with original Jefferson era trees in the background; Our group in the lab at Poplar Forest; View of the octagonal house, sometimes considered Jefferson’s masterpiece, during the SPA tour.