Written by Jamie Kouba

The most daunting part of earning your master’s degree has got to be picking a thesis topic. After a year of anxiety-inducing ideas coming and going, I was talking to a second-year graduate student about technological advances in archaeology and something finally clicked. As it turns out, there is a real need to establish digital repositories of 3D osteology comparative collections of both human and non-human specimens for researchers. Digital comparative collections are a valuable resource for

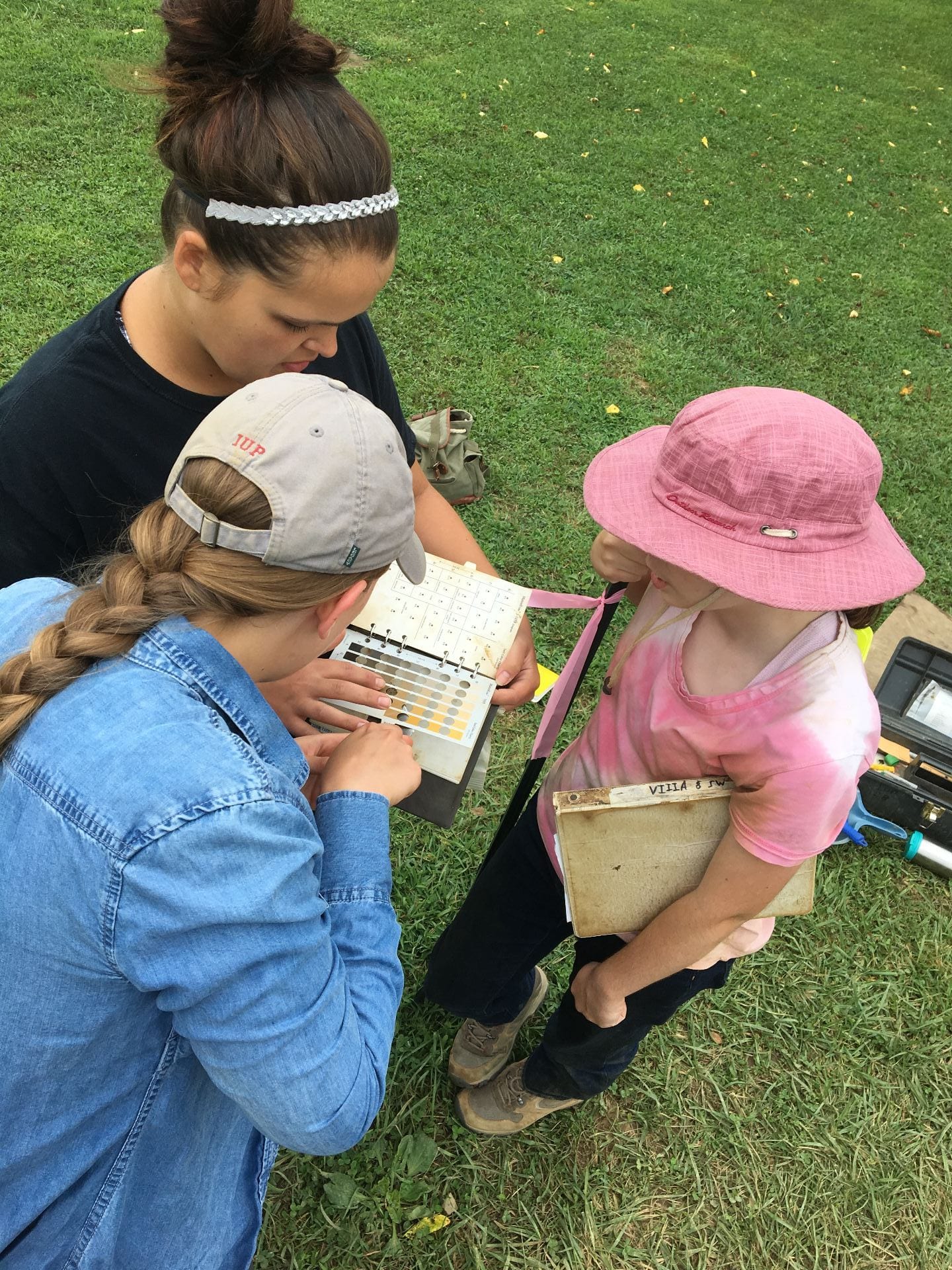

Jamie taking photographs of a bone to make her 3D model

zooarchaeologists, bioarcheologists, osteologists, and non-specialists alike. When a bone is recovered in the field, there are several questions that must be addressed immediately. First, is it bone? Second, is it human or animal. Typically, a bone specialist is called in to make identifications, or someone accesses a physical comparative collection and hopefully identifies the unknown element. However, an expert is not always available, and physical collections take up a lot of space, money, and time to maintain, limiting access to them. One of the ways to supplement those issues is to reference a digital collection. There are numerous websites out there, including Bone ID, Idaho Virtual Museum, and Sketchfab. Different websites use different formats for how they display their specimens. For instance, Bone ID provides 2D images, and Idaho Virtual Museum provides 3D scans, and Sketchfab is loaded with photogrammetric 3D models. This thesis was born out of one question: are all of these digital references equal in their ability to provide identifications?

While doing research, I found that there was a lot of information on 2D references and 3D scanned references, but very little on the use of photogrammetry to create 3D models. I had a feeling that 3D photogrammetric models would be the most effective form of digital reference. Photogrammetry uses a

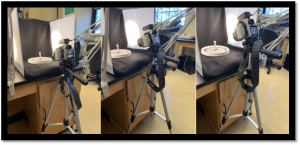

The photogrammetry set up

series of photos to create photo-realistic 3D models. An object is set on a rotating platform, and photos are taken all the way around it, from 3 different heights, then the object is rotated 180 degrees and the process is repeated. This technique allows for a 360-degree view to create a 3D model with. My thesis was designed to answer three research questions based on digital comparative collections: 1) Are photogrammetric 3D models useful in identifying osseous materials? 2) Can 3D models provide a more accurate identification than 2D photo references for osteological comparison? 3) Can 3D digital comparative specimens be used to supplement physical specimens that are not available?

In order to answer these questions, my thesis had several parts. The first thing that I did was to create my own digital repository by creating 3D models using photogrammetry. I made twenty models from the bones of bear, pig, cow, and human bone clones. I also made a second digital repository of 2D images of those same bones. Next, I designed a Qualtrics survey to test the efficacy of 2D/3D references. I surveyed 20 people, half received 2D references, half received 3D references. I would have preferred a larger sample, but the Covid-19 pandemic made it difficult to conduct these in person tests on a large scale. When the surveys were finished, I ran a statistical analysis to see how effective each reference was in aiding faunal identification. Along with the photogrammetry and survey parts of my thesis, I also analyzed a 3,600-element sample of faunal remains from Pocky Shell Ring in South Carolina. I made notes during my identifications as to whether I used digital collections or physical collections to assist in making my identifications.

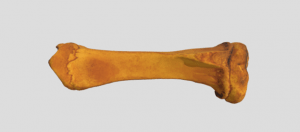

A 3D model created by Jamie

Upon starting this thesis, I assumed that the results of 2D references versus that of 3D photogrammetric references would be vastly different. What I discovered is that there are a lot of factors that can go into determining whether these references are effective. These include the size and completeness of the element itself, whether the desired identification is of bone type, species, or which side it came from. All of my participants reported to having less than five years of experience identifying bones, so none of them were experts. Overall people performed better on identifying bone type on a pig tibia, than they did on a bear metacarpal. Yet those same people preformed much better on identifying that the metacarpal was from a bear, than that the tibia was from a pig. What I can say for sure is that it appears that 3D photogrammetric references, on average, work as well as 2D references, with only about a 10% difference between them. As for my own faunal analysis, I determined that when there are appropriate digital resources available, they are effective in helping to make the correct identification. At the end of this, I feel that although more research is needed to confirm my results, photogrammetry can be used to create 3D digital references collections, which can be used to effectively identify unknown faunal remains.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram