Written by Gage Huey

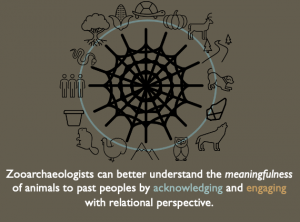

Zooarchaeology, or the study of animal remains in archaeological contexts has addressed the utilitarian aspects of human-animal interaction through decades of research on nutrition, seasonality, domestication, and the various techniques of carcass procurement and processing used by hunting cultures across the globe. As a result, traditional zooarchaeological interpretations rarely address the non-utilitarian meaningfulness of animals to the peoples whose material cultures we study. The way that archaeologists tend to think about human and animal relationships in the past typically reflects the structures and assumptions from our own worldview. These assumptions situate animals as an Other to humans, they serve our needs and can be used by humans but are fundamentally a different Thing. Over the centuries, these constructed differences between human beings and nature became more naturalized, fitting seamlessly into the colonial worldview that characterizes our “modern world”. Because scientific paradigms like anthropology were constructed within this worldview and the structures it produces. The interpretations we make as scientists reflect these as well. I believe this has led to misinterpretation of animal bones present at precontact sites through a largely Western perspective.

Zooarchaeology, or the study of animal remains in archaeological contexts has addressed the utilitarian aspects of human-animal interaction through decades of research on nutrition, seasonality, domestication, and the various techniques of carcass procurement and processing used by hunting cultures across the globe. As a result, traditional zooarchaeological interpretations rarely address the non-utilitarian meaningfulness of animals to the peoples whose material cultures we study. The way that archaeologists tend to think about human and animal relationships in the past typically reflects the structures and assumptions from our own worldview. These assumptions situate animals as an Other to humans, they serve our needs and can be used by humans but are fundamentally a different Thing. Over the centuries, these constructed differences between human beings and nature became more naturalized, fitting seamlessly into the colonial worldview that characterizes our “modern world”. Because scientific paradigms like anthropology were constructed within this worldview and the structures it produces. The interpretations we make as scientists reflect these as well. I believe this has led to misinterpretation of animal bones present at precontact sites through a largely Western perspective.

Indigenous peoples across the world (and specifically here on Turtle Island) see and saw the natural world in ways that would be incompatible with traditional zooarchaeological interpretation. So, my thesis research engages with an assemblage of animal remains through a perspective that acknowledges that prior to the arrival of Europeans (and continuing until today), Native peoples engaged with the environment not in terms of utilization, but in terms of relationships. The assemblage I’ve analyzed is from the 13th century (c.700 BP) Fort Ancient village,

Philo II (33MU76) located in Gaysport, Ohio. This village was constructed alongside an especially nice stretch of the Muskingum River known as the Philo Bottoms. This floodplain was home to Indigenous Ohioans for centuries, evidenced by the mound complex on the ridge overlooking

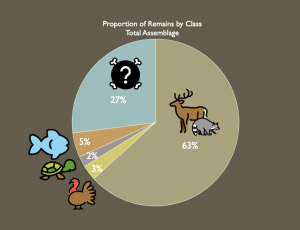

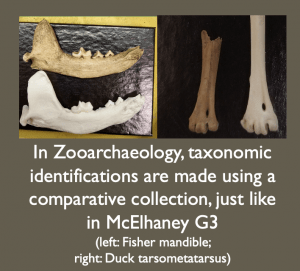

Philo II. These folks would’ve made pottery out of clay and mussel shells collected from the river, shared their pit-houses with dogs and stored maize, and hunted a variety of animals. The bones of these animals frequently ended up in subterranean “storage pits”, and vary in their number, species, and bone type (element) from feature to feature. Within the 55 features I analyzed, 27% of the bones were so fragmented they could only be reliably identified as indeterminate vertebrate. The remainder of the bones were identified to species when possible, but were broadly 63% mammal, 3% bird, 2% reptile, and 5% fish. The Philo Peoples would have had stories, songs, and all manner of cultural practices that engaged with these creatures not as animals in the Western sense, but as non-human persons that participated in society just as the humans did.

These relationships likely were not thought of in

an allegorical or metaphorical sense, they were a historical, lived reality. Imagine that a great ceremony was to be held in the plaza of Philo II, and the ceremony required music. The turtles whose shells were harvested to make instruments for the ceremony were taking part in the ceremony itself. In one sense, they were there (i.e., the turtles were plentiful) because they wanted to be there. And because the turtles had graciously attended the feast, there were particular cultural practices to ensure that they were honored and would continue to engage with the people in this way.

an allegorical or metaphorical sense, they were a historical, lived reality. Imagine that a great ceremony was to be held in the plaza of Philo II, and the ceremony required music. The turtles whose shells were harvested to make instruments for the ceremony were taking part in the ceremony itself. In one sense, they were there (i.e., the turtles were plentiful) because they wanted to be there. And because the turtles had graciously attended the feast, there were particular cultural practices to ensure that they were honored and would continue to engage with the people in this way.

Through my research, I am arguing that the pit features at Philo II are physical manifestations of the intersocial relationships between humans and non-human animal persons. The construction of these features would have disposed of animal bone and provided a means of constructing and naturalizing the relationships present between the Philo Peoples and the animals in which they shared an environment. They may also have connections to cultural practices of memory-making, linking them to their Late Woodland ancestors who moved great amounts of earth to combine bones, sediments, and artifacts into highly meaningful spaces. If zooarchaeologists acknowledge and engage with Indigenous scholars and the perspectives they bring to the field, it would provide an opportunity for old collections to be re-interpreted and analyzed in a new light that more accurately reflects the cultural context of the peoples whose cultures we study.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram