Written by Miriah Amend

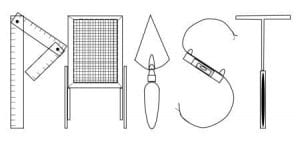

From the backwoods of Meadville, to the capital of Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Highway Archaeological Survey Team (PHAST) traveled around the state to conduct Phase I survey for several PennDOT projects this summer. The PHAST program provided archaeological field experience for four students from the IUP Department of Anthropology as well as GIS experience for a student from the Department of Geography and Regional Planning. The 2020 PHAST Crew completed 13 projects this summer, at most projects this consisted of digging shovel test pits, or STP’s, each one ranging from a few centimeters to a meter deep in the ground. We worked in a lot of different environments, forests, open fields, even a steep slope. What all these places had in common was being right next to a road or bridge that is planned to be improved or replaced by PennDOT.

Adapting to changes brought on by the COVID-19 Pandemic, the PHAST team did things a little differently this summer. Masking up and distancing during field work and van rides were new challenges, but this summer had familiar field challenges as well- many projects were surrounded by poison ivy or stinging nettles! With all of our projects being off busy roads, we always had to be careful when working, especially when crossing roads or bridges. Weather-wise, the crew was lucky, we only missed one day of field work due to thunderstorms! We spent this rainy-day cleaning artifacts and working on writing and making figures and maps for our reports. At the end of the day, archaeology could still be done, rain or shine!

Working alongside Dr. William Chadwick, the PHAST  crew also assisted in a cemetery relocation project just outside of Indiana this summer. The crew took turns using ground penetrating radar (GPR) technology in order to locate potentially unmarked burials. Getting experience running the GPR was a great way to get our feet wet in the exciting world of geophysics, and the preliminary analysis of the data suggests that there we did in fact pass over a few unmarked graves.

crew also assisted in a cemetery relocation project just outside of Indiana this summer. The crew took turns using ground penetrating radar (GPR) technology in order to locate potentially unmarked burials. Getting experience running the GPR was a great way to get our feet wet in the exciting world of geophysics, and the preliminary analysis of the data suggests that there we did in fact pass over a few unmarked graves.

Another project the team tackled was between Titusville and Meadville, up in the northwestern part of the state. There, our crew pulled out a variety of historic artifacts such as early 1900’s bottles, ceramic pieces, and various metal scraps, including an old metal shoehorn. This project area was near the foundation of known historic mill, so we weren’t too surprised to find historic material in this area, although I don’t think any of us expected it in this quantity!

Wrapping up the summer, the PHAST crew found even more artifacts- early historic pottery, glass, and even faunal remains! These were recovered during our last project, a bridge replacement near Murraysville. With these findings, additional STPs were required and this project turned from taking one day, to several. Who would have expected historic artifacts to be underneath a dense layer of rock just under the surface? It just goes to show the importance of Phase I survey, you never know what may be just below ground until you look!

Wrapping up the summer, the PHAST crew found even more artifacts- early historic pottery, glass, and even faunal remains! These were recovered during our last project, a bridge replacement near Murraysville. With these findings, additional STPs were required and this project turned from taking one day, to several. Who would have expected historic artifacts to be underneath a dense layer of rock just under the surface? It just goes to show the importance of Phase I survey, you never know what may be just below ground until you look!

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram