By Sarah Neusius

Summer is often the time for academic archaeologists to do fieldwork, but this summer my energies are focused on something different, and certainly not less important: the preservation and use of archaeological datasets. Most archaeologists know that there’s a lot more to archaeology than fieldwork, but even after the cleaning, cataloging, and analysis of materials, archaeologists still have a responsibility to the data they have generated. Articles and reports allow us to present our interpretations of what we have found, and curation facilities care for and make accessible the actual artifacts we recover. However, the observations we make about artifacts, in other words, the data we generate, also are important to curate. Keeping our data accessible to future archaeologists so they can reevaluate our conclusions in the light of new information and new theoretical perspectives is an archeological obligation, but one on which our discipline is just beginning to focus. The digital age provides both greater possibilities and greater challenges for us in this respect.

Of course it is now standard to record archaeological data in digital format. Everything from artefactual datasets and images to field notes and geophysical data can be stored digitally reducing concerns about storing paper records and images so that they will remain stable. On the other hand we all know that both software and hardware evolve at a lightening speed, rapidly making the formats we use obsolete and our data inaccessible. Nowadays archaeologists also are increasingly interested in the new ways to share their data that the internet provides. Along with web publishing there are many efforts to provide open access to archaeological data.

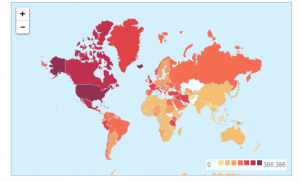

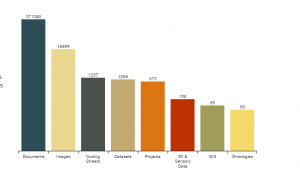

Among these the Digital Archaeological Record or tDAR, which has been developed by archaeologists and computer scientists under the auspices of Digital Antiquity now affiliated with Arizona State University. tDAR is an international repository for digital archaeological data, images, and documents that provides open access and includes integrative tools for analysis and has a core mission of helping archaeologists be better stewards of the data they generate. tDAR promises to keep these resources accessible in perpetuity by migrating to new digital formats as they become standard, and it also provides some powerful tools for integrating datasets created in different formats by different archaeologists so that comparison among site assemblages, settings, regions, and time periods is possible. These integrative aspects of tDAR allow archaeologists to address macro level questions in ways the published record does not because we can use and combine the original datasets rather than just the published summary data.

All of this is why my main project this summer is working with other zooarchaeologists who are part of the Eastern Archaic Faunal Working Group (EAFWG). Together and with funding from the National Science Foundation (BCS-1430754) we are preserving and integrating more than 50 Archaic Period (ca. 10,000-3,000 BP) faunal datasets and associated documents in tDAR. Eventually these datasets will be publicly accessible for students and other researchers in the EAFWG collection within tDAR.

These datasets were generated over the last sixty or more years by  archaeologists working on sites located in the interior parts of the Eastern North America. Because of a strong interest in human-environment interactions among American archaeologists during this period, recovery and analysis of animal remains as well as of bone and other artifacts was standard in these excavations. This tradition of emphasizing zooarchaeological analysis continues today among Midwestern and Southeastern

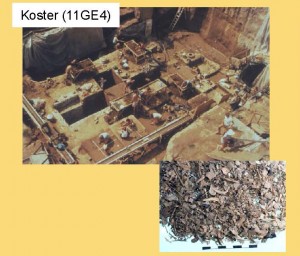

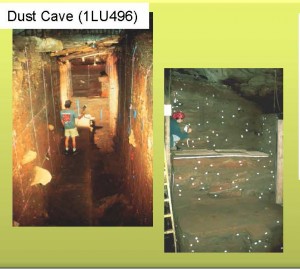

archaeologists working on sites located in the interior parts of the Eastern North America. Because of a strong interest in human-environment interactions among American archaeologists during this period, recovery and analysis of animal remains as well as of bone and other artifacts was standard in these excavations. This tradition of emphasizing zooarchaeological analysis continues today among Midwestern and Southeastern  archaeologists interested in all of the Pre-Columbian periods. Good preservation has meant that large amounts of animal bone as well as mussel and snail shell often are recovered and significant faunal datasets have been generated for this region. Some of the better known of these sites are emblematic of the Eastern Archaic including Modoc Rock Shelter and the Koster site in Illinois, the Green River shell middens such as Carlston Annis in Kentucky, and Dust Cave in Northern Alabama, but there are many other Archaic sites as well. Some of these

archaeologists interested in all of the Pre-Columbian periods. Good preservation has meant that large amounts of animal bone as well as mussel and snail shell often are recovered and significant faunal datasets have been generated for this region. Some of the better known of these sites are emblematic of the Eastern Archaic including Modoc Rock Shelter and the Koster site in Illinois, the Green River shell middens such as Carlston Annis in Kentucky, and Dust Cave in Northern Alabama, but there are many other Archaic sites as well. Some of these  datasets were recorded on paper only, and some of the earliest digital faunal datasets were also created as a result of these excavations. Moreover archaeologists in this region continue to generate significant faunal data today. Unfortunately, these data have remained dispersed across a wide variety of institutions and inaccessible to the larger archaeological community because they are recorded in a variety of formats and curated by individual researchers, some of whom are now deceased or no longer actively involved in Archaic period scholarship.

datasets were recorded on paper only, and some of the earliest digital faunal datasets were also created as a result of these excavations. Moreover archaeologists in this region continue to generate significant faunal data today. Unfortunately, these data have remained dispersed across a wide variety of institutions and inaccessible to the larger archaeological community because they are recorded in a variety of formats and curated by individual researchers, some of whom are now deceased or no longer actively involved in Archaic period scholarship.

The EAFWG includes zooarchaeologists from IUP, the Illinois State Museum, the University of Kentucky, Florida State University, the Illinois Archaeological Survey, State University of New York at Oneonta and the University of Michigan at Flint. Besides meeting at professional conferences and staying in touch through email and conference calls, we have held formal workshops. In fact, our most recent workshop was hosted here at IUP in mid-May and included my GA, Scott Rivas as well as myself.

Our goal is to use tDAR to preserve significant Archaic period faunal datasets and to bring them collectively to bear on research into the Archaic Period in Eastern North America. Not surprising traditional explanations for Archaic period variability and change, which have seen environment and demography as causal, have been questioned by contemporary researchers arguing that cultural identities, sociopolitical interactions, and ritual practices also explain some Archaic phenomena. In essence today’s archaeologists seek to understand Archaic period hunter-gatherers as more than participants in the ecosystem, and this raises new questions about the way Archaic data has been interpreted over the last half century or more. We think zooarchaeological data has much to contribute to these debates. Ultimately we have some macro-level questions about the variable use of aquatic resources by people who lived in this area during the Archaic period, which we believe will contribute meaningfully to better understanding of the Archaic period. However, we aren’t there yet, and instead are immersed in a long process.

Over the past year and through this summer I have been involved with myriad details, most of which would be far too boring for a blog such as this. However, I hope you can see why there are many steps in the EAFWG project. These have been accomplished with the help of several IUP undergraduate students and graduate students, and have included 1) creating digital databases from paper records in the first place, 2) finding and removing errors from digital datasets, 3) uploading digital datasets to tDAR, 4) providing metadata about what is in each dataset and what variables it contains, and 5) relating datasets created through the use of tDAR ontologies. We also have been exploring how comparable our Archaic datasets are in terms of taphonomy and contexts sampled, and working on measuring environmental and demographic variation during the Archaic period. By the end of the summer, we hope to begin to consider our research questions concerning the use of aquatic animals more directly.

For me personally, this summer project has meant little chance to be outside as much as I would prefer or to develop the muscles and fieldwork tan that I often do. Regardless, because the Archaic period was my first love in North American archaeology and this project is giving me an opportunity to revisit my dissertation research on the Koster site, it also is pretty exciting for me. Both collaboration with other zooarchaeologists, and looking at data I know well with new perspectives is a lot of fun. So if you encounter me this summer and find me slightly glassy eyed from staring at the computer screen, rest assured that I’m still absorbed in archaeology!