Tomorrow marks the 20th Anniversary of what we now refer to as 9/11. The horrid attack on The World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, New York is remembered as one of the worst terrorist attacks on U.S soil. The lives lost that day will forever be remembered, with almost 3,000 taken that morning.

An article from National Geographic, published this month, discusses the hundreds of thousands of artifacts that historians and archaeologists sought to recover months later. The artifacts missing “told the origin story of New York and the history of the enslaved men and women and immigrant workers who built the city into a global powerhouse.” Urban Archaeologist Sherrill Wilson ran the African Burial Ground project from the Six World Trade building that was destroyed from the fall of the North Tower during 9/11. The Six World Trade had a “large archaeology lab used to study artifacts unearthed during city construction.”

The African Burial Ground was uncovered in 1991, showing the presence of a large African community and the horrors of slavery that contributed a great deal to the building of the city. It now rests under Manhattan’s financial district. The plot of six-acres was given to freed Africans by Dutch colonists in the early 1600s, as a place for the Africans to bury their dead. More than 15,000 people were buried there with the passing of 150 years. Bones revealed the nasty circumstances the enslaved faced, their teeth shaving traditions erased and their bones fractured. The documentation, analysis, and artifacts, of the study of this site were stored in the Six World Trade building.

Also in 1991, the remnants of Five Points, “one of the world’s most densely populated neighborhoods and 19th-century Manhattan’s most notorious slum,” were discovered. This site gave the archaeological record artifacts from the working-class, more than 850,00 of them! These artifacts were also in the basement laboratory of Six World Trade. The studied artifacts showed a more understated side to those that lived there, with children’s toys and matching dishes, alluding to a life more sought on just “trying to dig themselves out of poverty,” or that some were not as impoverished as originally presumed.

September 11th, 2001 also destroyed the archives of Helen Keller, records of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and art by Rodin and Picasso. While the human remains of the African Burial Ground had already been transported to Howard University in D.C., much of the other artifacts and Five Points artifacts were buried. Nearly all the African Burial Ground artifacts were recovered, but what remained of the Five Points collection was records, the artifacts themselves demolished.

Today, a monument marks the African Burial Ground and researchers are even studying soil samples to study the human microbiome for some people who lived and died almost 400 years ago! It was also later discovered that 18 of the Five Points artifacts had been lent to the archdiocese of New York in 2000. These objects are now at the Museum of the City of New York, including the “prized” teacup artifact with the image of Father Matthew, an Irish priest.

The Father Mathew teacup, one of 18 surviving artifacts of the Five Points collection. (teacup_e4c9a1af69.jpg (712×397) (cuny.edu))

The Museum of the City of New York and the 9/11 Memorial Museum house relics from the history of September 11th, preserving wreckage and memorial artifacts to remind the world of not only the destruction from that day, but also the heroism. While the “loss of understanding ourselves and where we came from” in the archaeological world occurred that day, the human lives lost was certainly the greater tragedy. Please take a moment to remember and reflect on those who were taken and the events of that day.

Find more detail see the original article:

The archaeological treasures that survived 9/11 (nationalgeographic.com)

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

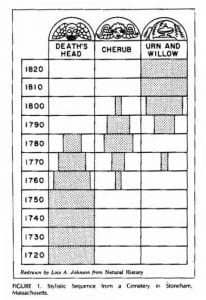

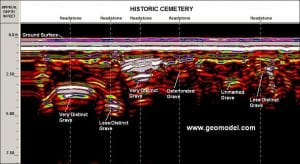

museums, many of which were either located in graves (grave goods) or in other sacred sites. Graves tend to have the precious metals (Agamemnon’s gold death mask) and intact artifacts that were deliberately placed with the deceased. Nowadays, archaeologists try their best to leave graves undisturbed if they can. Sometimes this is not an option, especially when graveyards are in the path of infrastructure projects. During those cases, archaeologists work with the community and descendants of the deceased to relocate the graves with all the respect that they deserve.

museums, many of which were either located in graves (grave goods) or in other sacred sites. Graves tend to have the precious metals (Agamemnon’s gold death mask) and intact artifacts that were deliberately placed with the deceased. Nowadays, archaeologists try their best to leave graves undisturbed if they can. Sometimes this is not an option, especially when graveyards are in the path of infrastructure projects. During those cases, archaeologists work with the community and descendants of the deceased to relocate the graves with all the respect that they deserve.