For many people Halloween is associated with the fun of dressing up in an elaborate costume, attending

Native American protesters stand outside the Phoenix office of a retailer of “sexy Native American” costumes last year. For some ethnic and racial groups, Halloween has long been haunted by costumes that perpetuate stereotypes and instances of cultural appropriation.

parties, and trick-or-treating. Costumes are a huge part of many different cultures and have very significant meaning. These costumes are often used as Halloween costumes. People, adults and children alike, will dress up as a Native American, geisha, Día de los Muertos costumes complete with skull makeup. Many people may see these costumes as accepting of other cultures but, in reality, it is cultural appropriation that makes culture into a caricature. All meaning is lost, and negative stereotypes are reinforced especially when they are degraded into a “sexy” costume. It is important to be aware of these stereotypes and the negative emotions felt by those whose cultures are being represented.

One of the main costumes every year is the Native American. This has a number of problems. First, the costume itself

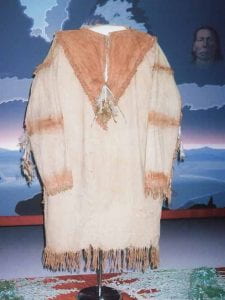

The Ghost Dance Shirt that many costumes are based off of. It looks similar to those seen in stores.

is based on the clothing worn by tribes during a period of American expansion westward. This was an extremely violent time when Native peoples were killed, forced from their homes, starved, and given many illnesses such as tuberculosis and smallpox. Each time someone wears one of the standard “Indian” costumes, they are returning the still present Native American culture to a time of violence and colonial domination. The costume itself is a form of continued domination over descendant communities by those in power. Not only do these costumes freeze Native American culture in the violent past but they are often based on the traditional Ghost Dance shirt. The Ghost Dance shirt worn during traditional events was meant to protect the wearer from harm, specifically the harm inflicted by the U.S. Cavalry. This movement ended with the bloody massacre of 300 men, women, and children at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890. This shirt is not a costume, it is a representation of an extremely violent period and a symbol of protection.

Another common costume is the catrina dress worn during Día de los Muertos. A quick Google search of “catrina dresses” results in Amazon and Esty costumes, a Pintrest how-to link, and images mostly depicting sexily dressed women in black, red, and sometimes colorful dresses with skull make up and flowers. This is not right or accurate. Many people see Día de los Muertos as a Halloween spin-off

Traditional Dia de los Muertos garb and makeup

but in reality, it is a deeply seated cultural practice to honor and celebrate the dead. The only connection it has to Halloween in a date (although it lasts for three days) and a skeleton motif. It is part of someone’s culture that is being exploited for the entertainment of others who do not understand the meaning behind the outfit. The Eiteljorg Museum is hosting a virtual celebration of Día de los Muertos between October 28 and November 2 featuring traditional dances, music, talks, art, and so much more. The link is here. Event like this teach people about the importance of understanding someone else’s culture by allowing people to experience it. If you want to dress in a catrina, become part of the culture and truly celebrate the event as it is meant to be celebrated.

Wearing a cultural costume for Halloween is offensive and diminished the meaning of that culture. It is racists and should not be done. Instead of dressing as an Indian warrior or princess, use the opportunity to teach the public, children especially, how to respect other cultures and bring awareness to their current plights rather than keeping them frozen in their violence filled past.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Some related and interesting links are here-

https://www.npr.org/2019/10/29/773615928/cultural-appropriation-a-perennial-issue-on-halloween

https://www.lakotatimes.com/articles/anniversary-of-return-of-ghost-dance-shirt/

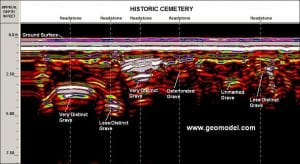

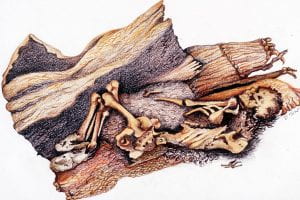

museums, many of which were either located in graves (grave goods) or in other sacred sites. Graves tend to have the precious metals (Agamemnon’s gold death mask) and intact artifacts that were deliberately placed with the deceased. Nowadays, archaeologists try their best to leave graves undisturbed if they can. Sometimes this is not an option, especially when graveyards are in the path of infrastructure projects. During those cases, archaeologists work with the community and descendants of the deceased to relocate the graves with all the respect that they deserve.

museums, many of which were either located in graves (grave goods) or in other sacred sites. Graves tend to have the precious metals (Agamemnon’s gold death mask) and intact artifacts that were deliberately placed with the deceased. Nowadays, archaeologists try their best to leave graves undisturbed if they can. Sometimes this is not an option, especially when graveyards are in the path of infrastructure projects. During those cases, archaeologists work with the community and descendants of the deceased to relocate the graves with all the respect that they deserve.