IUP has officially started again so it’s time Trowels and Tribulations got back into action. One of IUP’s new policies regarding COVID-19 is that all students must wear masks. Masks are a culturally significant item that is present in many different countries and used in a variety of rituals from burials to rites of passage and religious practices.

One of the most famous masks was discovered my Heinrich Schliemann in his 1876 excavation of Mycenae in Greece. During his excavations, Schliemann’s team discovered a large grave circle, now called Grave Circle A, in which a number of burials were discovered. Five of these burials contained gold burials masks. Schliemann concluded that one of these burials and masks belonged to the legendary Greek hero and king Agamemnon. While never actually authenticated by Schliemann as Agamemnon, this particular mask was the most spectacular and thus associated with the hero king. Unfortunately for the often overly fanciful Schliemann the burials were later dated to 300 years after the Trojan War in which Agamemnon fought and thus were not likely to be associated with him. The most interesting point about this mask is that it is so perfectly preserved and distinctive that some scholars believe it to be a hoax, which Schliemann is known for doing. Along with the mask looking completely different from the others, Schliemann himself acted in a suspicious manner around the time of his discovery. He had left the site for two days just before it was discovered and then closed the site directly after its discovery. While not suspicious in itself, he was known to purchasing and commissioning replicas of objects, such as the bust of Cleopatra found in Alexandria, and planting them in his sites. Despite these doubts of authenticity, other gold masks have been recovered from the grave circle and appear to be authentic. (For more click here and here)

Three Mycenaean masks all of gold. The middle is the Mask of Agamemnon. It has much more distinctive features, extended ears, larger eyes, smaller forehead, and a well groomed beard and mustache that is not present on the other two.

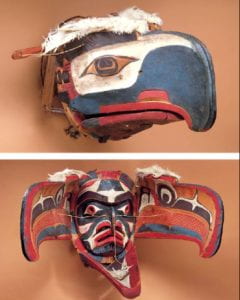

I little closer to home, masks are used my name Native American traditions (modern and past) in rituals and ceremonies. One very interesting mask type is called transformation masks and are commonly worn by tribes along the Northwest Coast of North America. Transformation masks are made from wood and decorated to look like animals, ancestors, or mythical beings. The wearer can manipulate the masks using strings so at specific moments in the ceremony, the performer will transform into another creature or ancestor by opening up the mask. They are most well known for being used during Knakwaka’wakw potlatch ceremonies during which the masks can convey status and genealogy. Many other tribes throughout North America use masks in their ceremonies. However, because of the materials they are made from, wood, leather, and other degradable materials, they are not often recovered in archaeological contexts. Some tribes such as the Cherokee nearly lost the mask making traditions when they were forcible removed from traditional lasts. Fortunately, Native American artists are working to restore these lost traditions. (To learn more click here)

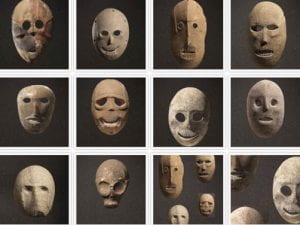

Ancient Neolithic stone masks

The oldest masks in the world were discovered in 1983 in Nahal Hemar cave along the Dead Sea. The masks date to around 9,000 years and were also discovered with the oldest known glue along with baskets and beads. Some masks still show pigment meaning that they were likely painted. These stone masks weigh between one and two kilograms (about a 2-4 pounds) are each unique to one another and possible represent particular people. The actual use of these masks in unknown but Dr. Debby Hershman of the Israel Museum theorizes that they were likely worn by tribal leaders or shamans during burial and other death rituals. Since the masks have holes for the eyes, mouth, a dent for a nose, and small holes on either side of the face, it is likely they were worn by a person. (View sources here and here)

Masks have been an important part of history and are still important today for more than just ceremonial practices. These masks were used to symbolize ancestors or spirits. They were not worn everyday and help great powers over those who did wear and likely those who made them. Our masks do not share the same transformative powers, but they are important. Keep on wearing your masks and make a story out it.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram