Written by Heather Lash

For many people, consuming food is one of the best parts of each day. The act of eating provides for most, a moment to rest, spend time with family, and relate to others. It is especially pleasing for individuals who enjoy preparation and cooking of foodstuffs. And while the act of eating is universal, it is not associated with positive connotations for all people. In fact, the way a person is shaped and influenced by their cultural norms and traditions influences the way they associate with food, foodstuffs, and foodways. Foodways – the cultural, economic, political, and social aspects involved in the act of eating – influence the production and consumption of food-related materials. These overlapping spheres of influence effect the creation and continuation of foodways and food traditions within cultures.

By focusing on the daily act of eating, and all processes involved in production and consumption of food, the agency of communities and individuals can be illuminated. Reconstructing food processes contributes to better understanding one aspect of daily life that introduces choice based on preference. In my thesis, “Foodways of Pre- and Post-Emancipation African Americans at James Madison’s Montpelier: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Food Preference and Food Access,” I explore African foodways through Zooarchaeological identification and analysis. By matching each bone to IUPs Zooarchaeological Comparative Collection, and determining the presence and absence of different animals in the collection, Trends describing preference of food and access to foodstuffs can be clearly differentiated. At James Madison’s house, Montpelier, located in Virginia, the need exists for pre- and post- emancipation subsistence practices to be contrasted, compared, and evaluated. Therefore, detailing differences and similarities between one group of enslaved individuals and one free family across the Montpelier property can also delineate post-Emancipation effects on food procurement and the utilization of foodstuffs.

By focusing on the daily act of eating, and all processes involved in production and consumption of food, the agency of communities and individuals can be illuminated. Reconstructing food processes contributes to better understanding one aspect of daily life that introduces choice based on preference. In my thesis, “Foodways of Pre- and Post-Emancipation African Americans at James Madison’s Montpelier: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Food Preference and Food Access,” I explore African foodways through Zooarchaeological identification and analysis. By matching each bone to IUPs Zooarchaeological Comparative Collection, and determining the presence and absence of different animals in the collection, Trends describing preference of food and access to foodstuffs can be clearly differentiated. At James Madison’s house, Montpelier, located in Virginia, the need exists for pre- and post- emancipation subsistence practices to be contrasted, compared, and evaluated. Therefore, detailing differences and similarities between one group of enslaved individuals and one free family across the Montpelier property can also delineate post-Emancipation effects on food procurement and the utilization of foodstuffs.

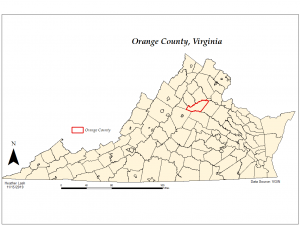

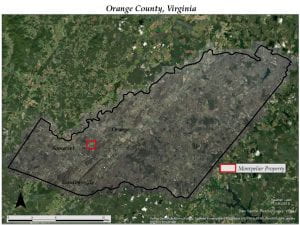

The Montpelier plantation is located in Orange, Virginia, about 30 miles north of Charlottesville. The main house was built by James Madison Sr. and then later occupied by former President, James Madison Jr., and his family from 1764 to 1844. Throughout their “Retirement Period” (1809-1844), the period of significance for this research, James and Dolley Madison hosted guests for celebrations and cookouts. Preparation of the festivities were facilitated by their three groups of enslaved individuals—domestic enslaved individuals, artisans, and field hands (Reeves and Greer 2012:73). These enslaved individuals formed a large community across the plantation before emancipation, 1764 to 1860. After emancipation, formerly enslaved individuals, such as George Gilmore, were responsible for their own subsistence. This juxtaposition of two time periods provides a comparison for pre- and post- emancipation food preference and consumption trends.

Modification of food was a very important way of continuing and reinforcing traditions. The application of African traditions to foodstuffs, food preparation, and food consumption due to the repetition of social actions (i.e. tradition), resulted in an identity linked to food. This Africanization, recognized as the modification of available resources, applied to foodways, and contributed to a phenomena that embodies much of the South, and is known as “Soul Food.” Focusing on Enslaved African and Black Freedman culture helps provide an outlet for African voices; individuals overlooked as creators of their own history and culture. Overall, foodways help conceptualize the story of perseverance and strength of pre- and post- emancipation families.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram