Written by Zac Fischer,

My thesis research focuses around the Squirrel Hill site, a Johnston phase (1450-1590AD) Monongahela village near New Florence, PA. More specifically, this research focuses on the debitage and specific cherts found at the site. For those less familiar with the jargon, I’m looking at the specific types of stones that would be used to produce tools and the chipped fragments of that stone. What I want to know can be summed up in three questions. First, do different chert types have different chemical signatures or fingerprints? Second, what chert types are present at Squirrel Hill and where are they coming from? Are the cherts local and thus sourced by the Monongahela or are there also non-local cherts which could be representative of interaction such as trade with other cultural groups. Third, if multiple chert types are present, do they spatially segregate between the typical Monongahela domestic structure and the anomalous rectangular structure at the site? To answer these questions my research methods can be broken into two main points: chemically examining chert types to try and produce a chemical fingerprint; comparing the chert types and debitage from Squirrel Hill to the Johnston site (another Johnston phase Monongahela village), comparing across the site, and comparing between traditional domestic structures and an anomalous rectangular structure at the site.

My thesis research focuses around the Squirrel Hill site, a Johnston phase (1450-1590AD) Monongahela village near New Florence, PA. More specifically, this research focuses on the debitage and specific cherts found at the site. For those less familiar with the jargon, I’m looking at the specific types of stones that would be used to produce tools and the chipped fragments of that stone. What I want to know can be summed up in three questions. First, do different chert types have different chemical signatures or fingerprints? Second, what chert types are present at Squirrel Hill and where are they coming from? Are the cherts local and thus sourced by the Monongahela or are there also non-local cherts which could be representative of interaction such as trade with other cultural groups. Third, if multiple chert types are present, do they spatially segregate between the typical Monongahela domestic structure and the anomalous rectangular structure at the site? To answer these questions my research methods can be broken into two main points: chemically examining chert types to try and produce a chemical fingerprint; comparing the chert types and debitage from Squirrel Hill to the Johnston site (another Johnston phase Monongahela village), comparing across the site, and comparing between traditional domestic structures and an anomalous rectangular structure at the site.

A portion of my thesis hinges on our department’s portable X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF) device. PXRF is a non-destructive analytical tool that measures chemical composition by directing x-rays at a sample. This causes your sample to emit energy at specific energies and wavelengths that are characteristic of its elemental components. The device detects the specifics and measures the different components in parts per million. From the chemical data that I am collecting through this method, I will attempt to produce a chemical signature or fingerprint for cherts accessible to the Monongahela tradition. Similar studies have occurred with varying degrees of success, so this may or may not work. If it does work, the chemical fingerprints should help in analyzing chert types of debitage from Squirrel Hill and potentially other Monongahela sites. How would this help? In the case of debitage from Squirrel Hill, most lithic flakes are tertiary, presumably from late stage tool production or tool sharpening and reworking. In other words, these flakes are very small and cherts accessible by the Monongahela at Squirrel Hill can be easily confused due to similar colors and textures. Having less material makes it somewhat more difficult to correctly identify cherts. So, if we could chemically examine flakes that are unable to be identified otherwise and compare the data to chemical fingerprints, we could potentially identify the chert type. If a chert does not match with any of the fingerprints, then it could be suggested that it came from a non-local source. The presence of such cherts could be representative of interaction with other cultural groups like through trade.

Even if my chemical analysis does not go as planned, I will still be examining chert types and debitage from Squirrel Hill. Again, I plan on comparing at the intersite and intrasite levels. I’m comparing the debitage between Squirrel Hill and the Johnston site to look at variation in chert usage within Johnston phase sites. Knowing the difference in chert usage between sites of the same temporal, regional, and cultural affiliation should help guide my interpretations of later comparisons. Next, I would compare across Squirrel Hill, for example the northern and southern portions of the site, to see how chert usage varies at the site in a more general sense. Finally, the comparison takes another look at the site by comparing between typical domestic structures and the unusual rectangular structure. Why am I concerned about this rectangular thing? Well, it’s out of the ordinary for Monongahela sites. How out of the ordinary? A typical Monongahela domestic structure is round and about 3-4m in diameter, but they have been known to be upwards of 6m in diameter (Dragoo 1955). The anomaly is about 6-7m wide and 35m long. Why is it at the site? We don’t truly know, but it has been hypothesized that the unusual nature of the structure could be representative of interaction with or habitation by another cultural group. Ultimately, I hope that my analysis will bring us a step closer to understanding who occupied that structure by examining the cultural material within.

I will still be examining chert types and debitage from Squirrel Hill. Again, I plan on comparing at the intersite and intrasite levels. I’m comparing the debitage between Squirrel Hill and the Johnston site to look at variation in chert usage within Johnston phase sites. Knowing the difference in chert usage between sites of the same temporal, regional, and cultural affiliation should help guide my interpretations of later comparisons. Next, I would compare across Squirrel Hill, for example the northern and southern portions of the site, to see how chert usage varies at the site in a more general sense. Finally, the comparison takes another look at the site by comparing between typical domestic structures and the unusual rectangular structure. Why am I concerned about this rectangular thing? Well, it’s out of the ordinary for Monongahela sites. How out of the ordinary? A typical Monongahela domestic structure is round and about 3-4m in diameter, but they have been known to be upwards of 6m in diameter (Dragoo 1955). The anomaly is about 6-7m wide and 35m long. Why is it at the site? We don’t truly know, but it has been hypothesized that the unusual nature of the structure could be representative of interaction with or habitation by another cultural group. Ultimately, I hope that my analysis will bring us a step closer to understanding who occupied that structure by examining the cultural material within.

Dragoo, Don

1955 Excavations at the Johnston Site, Indiana County, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 25(2) 85-141.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

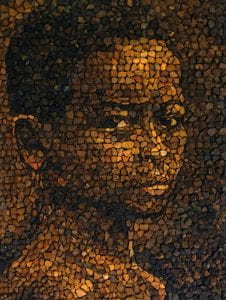

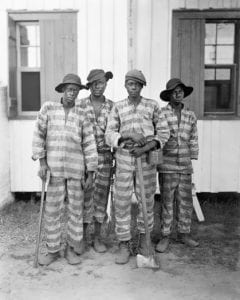

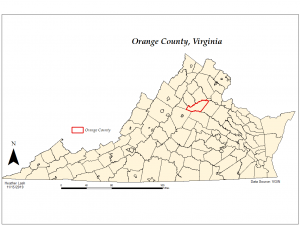

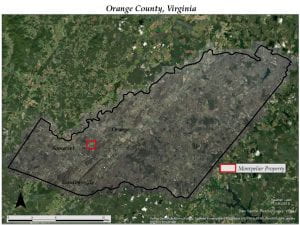

By focusing on the daily act of eating, and all processes involved in production and consumption of food, the agency of communities and individuals can be illuminated. Reconstructing food processes contributes to better understanding one aspect of daily life that introduces choice based on preference. In my thesis, “Foodways of Pre- and Post-Emancipation African Americans at James Madison’s Montpelier: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Food Preference and Food Access,” I explore African foodways through Zooarchaeological identification and analysis. By matching each bone to IUPs Zooarchaeological Comparative Collection, and determining the presence and absence of different animals in the collection, Trends describing preference of food and access to foodstuffs can be clearly differentiated. At James Madison’s house, Montpelier, located in Virginia, the need exists for pre- and post- emancipation subsistence practices to be contrasted, compared, and evaluated. Therefore, detailing differences and similarities between one group of enslaved individuals and one free family across the Montpelier property can also delineate post-Emancipation effects on food procurement and the utilization of foodstuffs.

By focusing on the daily act of eating, and all processes involved in production and consumption of food, the agency of communities and individuals can be illuminated. Reconstructing food processes contributes to better understanding one aspect of daily life that introduces choice based on preference. In my thesis, “Foodways of Pre- and Post-Emancipation African Americans at James Madison’s Montpelier: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Food Preference and Food Access,” I explore African foodways through Zooarchaeological identification and analysis. By matching each bone to IUPs Zooarchaeological Comparative Collection, and determining the presence and absence of different animals in the collection, Trends describing preference of food and access to foodstuffs can be clearly differentiated. At James Madison’s house, Montpelier, located in Virginia, the need exists for pre- and post- emancipation subsistence practices to be contrasted, compared, and evaluated. Therefore, detailing differences and similarities between one group of enslaved individuals and one free family across the Montpelier property can also delineate post-Emancipation effects on food procurement and the utilization of foodstuffs.

For the most part, they were treated and paid well, able to travel with their families, and able to retain their traditional ways of life. Despite these positive aspects of the show, they were still viewed as warlike savages preventing the expansion of civilization into the West. The Native American victory at Little Big Horn was even used to show audiences why westward expansion is needed. In the 1890s Buffalo Bill’s employed hundreds of Native Americans, vastly outnumbering the number of cowboys and cowgirls.

For the most part, they were treated and paid well, able to travel with their families, and able to retain their traditional ways of life. Despite these positive aspects of the show, they were still viewed as warlike savages preventing the expansion of civilization into the West. The Native American victory at Little Big Horn was even used to show audiences why westward expansion is needed. In the 1890s Buffalo Bill’s employed hundreds of Native Americans, vastly outnumbering the number of cowboys and cowgirls.