By: Genevieve Everett

At the beginning of September, one week into the second year of my graduate studies I packed my car and headed up to Maine to help friends of mine that had received grants to excavate near a quarry site for nine days. I’ve spent countless hours in cars on road trips up and down the east coast; so spending half a day at the drivers seat is very familiar to me. All I require is good music or talk radio and a leg stretch every now and again. Amanda Telep, a recent IUP undergraduate came along for the adventure.

On our first day we met up with Heather Rockwell and Nathaniel Kitchel and the rest of the crew. Nathaniel and Heather both received their PhDs from the University of Wyoming, however, they have focused much of their research in New England. Before we arrived at our campsite, we had to drive close to 55 miles on bumpy narrow logging roads. To give you an idea of how remote this area was, when Amanda and I were leaving to cross from the United States into Canada, the boarder officer asked, “Are you lost?” We arrived at our campsite at dusk just as the rain began, and yes, the rain stayed with us for most of the trip. I kept joking that I had “water front property”, because a huge puddle had formed just outside my tent. After setting up, we all huddled inside of the canvas tent to eat salsa mixed with mac and cheese, which can only be described as hot gooey deliciousness. We used the canvas tent as our meeting place every morning and evening for meals. The area we were in is pretty remote; so all provisions were brought in with the hope that nothing was left behind.

Okay, so onto the archaeology, and why we were there…

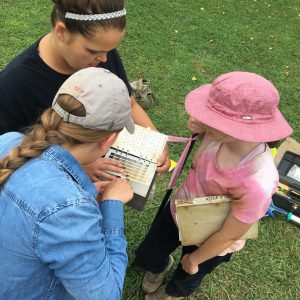

Every morning we drove into the site looking out for the giant logging trucks that seem to creep up on you out of nowhere. On our first official day in the field, Nathaniel and Heather gave us a tour of the quarry and the area where Heather was focusing her research. So far, the site(s) have a prehistoric component, however no temporal determination has been made. Several transects were laid out to cover Heather’s area of interest (eventually each STP was plotted with a GPS). Shovel testing made it possible for Heather to begin determining where concentrations of artifacts were being recovered, and finding the boundary (based on sterile shovel tests). We were finding hundreds of flakes every day, especially in the tree throw that took almost an entire day to excavate!

On one of the last days I had an opportunity to go up to the quarry site where Nathaniel was excavating a 1 meter x 1 meter test unit at the base of the quarry outcrop. This outcrop is a Munsungun chert source, a raw material utilized by prehistoric peoples to make stone tools. Interestingly enough, Munsungun chert is found in the form of lithics and lithic debitage at many Paleoindian sites in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, hundreds of miles away. By the time I got up to the quarry site Nathaniel and Tom (another volunteer) had excavated roughly 30 cm through natural shatter and cultural debris (flakes, etc). It was almost overwhelming how much cultural material was present at the quarry. There was a peaceful eeriness about this area, broken up by the chatter of angry red squirrels from time to time.

A couple of our afternoons were spent driving to and from (a total of about 45 miles) what we dubbed “Cell Phone Mountain” to check email and make phone calls, because there is zero cell service out there. I have to admit, it was really nice being disconnected from the world for a few days. The view from on top of “Cell Phone Mountain” was phenomenal, especially since fall starts early up there, so we had a chance to see some really gorgeous fall foliage. Every night we took turns making dinner and cleaning up. On those evenings when it wasn’t raining we sat around a fire admiring the night sky unobstructed by light pollution. We also managed to make a considerable dent in the beer that we all brought along with us, because archaeologists “work hard, play harder”. Honestly, we were in bed most nights before 10 pm, because we were up every morning at 6:30 am. So yeah, not much in the way of partying.

All in all, this trip was an incredible professional and educational experience. I got to meet new colleagues that I hope I will have a chance to work with one day. I was also offered invaluable advice about starting/finishing my thesis. If I was forced to say one bad thing to say about this trip, it would be that we didn’t see a living/breathing moose, only a reproduction of one at the Kennebunk rest stop. Maybe next time!