Written by Angela Rooker

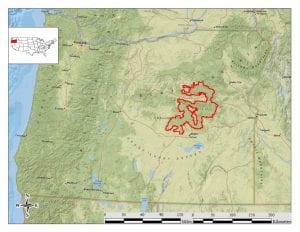

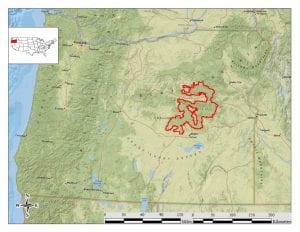

Malheur National Forest

Ever since I started working as a seasonal archaeological technician on the Malheur National Forest in eastern Oregon, I’ve been fascinated by the diversity of plant life in this extraordinary desert. So it was only natural to pick a thesis topic related to precontact plant use. Working for a National Forest and other public archaeology experiences also got me interested in finding ways to share the knowledge gained in ways that are meaningful to the local and descendant communities. I was able to roll both of these interests together into a two-part thesis. First it will create a precontact context for geophyte use on the Malheur National Forest and thus add to the understanding of geophyte utilization in eastern Oregon. Second, it will propose a management plan for geophytes on the Malheur National Forest as well as better ways to manage Historic Properties of Religious and Cultural Significance to Indian Tribes (HPRCSIT)s and Traditional Cultural Properties.

Geophytes, such as camas and Lomatium, are plants with edible, underground, storage organs (ie roots, rhizomes, and tubers), and have been important in the diets of the American Indians living in the Pacific Northwest for thousands of years. Among the most

Apiaceae Plant

commonly utilized geophytes were common camas (Camassia quamash), wild carrot/yampa (Perideridia gairdneri), Lomatium (Lomatium sp.), umbellifers/parsley family (Apiacae), bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva), balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sp.) and wild onion (Allium sp.). Geophytes are major sources of carbohydrates, but also provide protein, vitamins, and minerals depending on the species. Inulin, the major carbohydrate in camas, onions and balsamroot and to a lesser extents Lomatium is largely indigestible until cooked. Traditionally, many geophytes were processed on hopper mortars and then cooked in earth ovens, features still visible on the landscape today and protected as cultural resources. Geophyte use is most prevalent on the Columbia Plateau and portions of the northern Great Basin that border the Columbia Plateau. However, many studies only examine the Plateau or the Great Basin (Fowler and Rhodes 2006 and Cummings 2004).

Camas Plan

This can make it hard to determine the diet of people that lived in between the Great Basin and the Columbia Plateau, including the area that now encompasses the Malheur National Forest. Furthermore, geophytes themselves generally do not preserve well in the archaeological record, so much of the evidence relating to their use is inferred by the presence of digging sticks, hopper mortars, other grinding and pounding tools (including grinding slabs and pestles), earth ovens, storage pits, and upper-elevation base camps (Lepofsky 2004:426-427; Lepofsky and Peacock 2004:130). Modern descendants are not as dependent on wild foodstuffs as their ancestors,

Bitterroot Plant

yet traditional foods, especially plant foods, remain meaningful as delicacies and as touchstones of Native identity (Soucie 2007:57-59; Aikens and Couture 2007:278-279). For example, land owned by the Burns Paiute Tribe contains the Biscuit Root Area of Critical Environmental Concern, a 6,500 acre preserve of a traditional root gathering area (Soucie 2007:57). The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla American Indian Nation has the “First Foods” program; the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs has four yearly feasts (the Root Feasts, The First Catch, The Huckleberry Feast, and the Celery Feast), all of which are used to educate and connect tribal members with traditional foods.

Second, this thesis explores “Historic Property of Religious and Cultural Significance to Indian Tribes” (HPRCSIT), one of the property designations identified as part of the legal mandate established by National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) that requires federal agencies (or those utilizing federal money, working on federal land, requiring a federal permit, or preforming actions subject to federal oversight) to consider the effects of

Hopper Mortar

their actions on natural and cultural resources. HPRCSIT is a recent designation, first appearing around 2016. It came about to offer American Indians more control over actions that affect sacred sites and other places important to their contemporary cultural practices (Donn Hann, personal communication 2019). American Indian Nations are hopeful that the HPRCSIT designation will offer greater legal protection because it takes language directly from 36CFR800.2(D), namely the phrase “Federal agencies should be aware that frequently historic properties of religious and cultural significance are located on ancestral, aboriginal, or ceded lands of Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations and should consider that when complying with the procedures in this part,” (emphasis added). I hope this project will provide an example of combining academic research and management practices to find the best balance between cultural heritage and the other activities on public lands, such as recreation, thinning and timber harvesting, cattle grazing, and prescribed fire.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

an allegorical or metaphorical sense, they were a historical, lived reality. Imagine that a great ceremony was to be held in the plaza of Philo II, and the ceremony required music. The turtles whose shells were harvested to make instruments for the ceremony were taking part in the ceremony itself. In one sense, they were there (i.e., the turtles were plentiful) because they wanted to be there. And because the turtles had graciously attended the feast, there were particular cultural practices to ensure that they were honored and would continue to engage with the people in this way.

an allegorical or metaphorical sense, they were a historical, lived reality. Imagine that a great ceremony was to be held in the plaza of Philo II, and the ceremony required music. The turtles whose shells were harvested to make instruments for the ceremony were taking part in the ceremony itself. In one sense, they were there (i.e., the turtles were plentiful) because they wanted to be there. And because the turtles had graciously attended the feast, there were particular cultural practices to ensure that they were honored and would continue to engage with the people in this way.

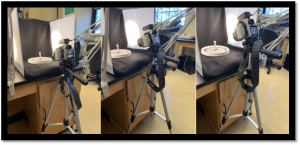

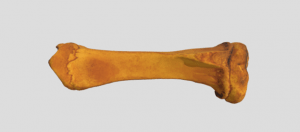

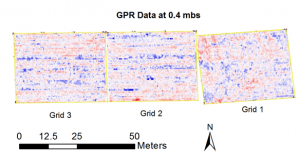

My thesis research focuses around the Squirrel Hill site, a Johnston phase (1450-1590AD) Monongahela village near New Florence, PA. More specifically, this research focuses on the debitage and specific cherts found at the site. For those less familiar with the jargon, I’m looking at the specific types of stones that would be used to produce tools and the chipped fragments of that stone. What I want to know can be summed up in three questions. First, do different chert types have different chemical signatures or fingerprints? Second, what chert types are present at Squirrel Hill and where are they coming from? Are the cherts local and thus sourced by the Monongahela or are there also non-local cherts which could be representative of interaction such as trade with other cultural groups. Third, if multiple chert types are present, do they spatially segregate between the typical Monongahela domestic structure and the anomalous rectangular structure at the site? To answer these questions my research methods can be broken into two main points: chemically examining chert types to try and produce a chemical fingerprint; comparing the chert types and debitage from Squirrel Hill to the Johnston site (another Johnston phase Monongahela village), comparing across the site, and comparing between traditional domestic structures and an anomalous rectangular structure at the site.

My thesis research focuses around the Squirrel Hill site, a Johnston phase (1450-1590AD) Monongahela village near New Florence, PA. More specifically, this research focuses on the debitage and specific cherts found at the site. For those less familiar with the jargon, I’m looking at the specific types of stones that would be used to produce tools and the chipped fragments of that stone. What I want to know can be summed up in three questions. First, do different chert types have different chemical signatures or fingerprints? Second, what chert types are present at Squirrel Hill and where are they coming from? Are the cherts local and thus sourced by the Monongahela or are there also non-local cherts which could be representative of interaction such as trade with other cultural groups. Third, if multiple chert types are present, do they spatially segregate between the typical Monongahela domestic structure and the anomalous rectangular structure at the site? To answer these questions my research methods can be broken into two main points: chemically examining chert types to try and produce a chemical fingerprint; comparing the chert types and debitage from Squirrel Hill to the Johnston site (another Johnston phase Monongahela village), comparing across the site, and comparing between traditional domestic structures and an anomalous rectangular structure at the site.