Category Archives: Native American Heritage

Celebrating National Native American Heritage Month

During the month of November, we celebrate National Native American Heritage Month, or American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month. This celebration is in honor of the original inhabitants of America. Organizations across the States come together to learn about and commemorate the traditions, languages, contributions, and heritage of Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and other Island communities during November. This post was originally written by former Public Archaeology Graduate Assistant Bridget Roddy two years ago, and the piece is so well written, I did not want to attempt improving upon it.

Honoring the history of the Indigenous people of this land began in 1900 when Dr. Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca Indian and director of the Museum of Arts and Science in New York, convinced the Boy Scouts of America to observe a day for Native Americans. After this, an American Indian Day was declared in 1916. In 1976, a Native American Awareness Week was declared by Congress, and in 1990 former President George H.W. Bush signed a joint congressional resolution to designate November as National American Indian Heritage Month. Since 1994, other proclamations have been made with variations to the name; Native American Heritage Month and National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month are two. It was former President Barack Obama who named November as National Native American Month, which is how we continue to refer to it as of today.

To honor this month, let’s reflect on some Native American archaeologists who have made incredible contributions to the preservation of this county’s heritage and past. Arthur C. Parker was born in 1881 on the Seneca tribe’s Cattaraugus Reservation in New York. He was descended from a long line of Seneca leaders on his father’s side, however, because Seneca clan member ship is matrilineal and both his grandfather and father married women of European descent, neither his father nor him were considered to be Seneca. His family moved to White Plains, NY in 1892 and graduated from high school in 1897. Although he attended Centenary Collegiate institute in New Jersey and Dickinson Seminary in Pennsylvania, he did not graduate from either. However, he continued to do archaeological work while in college and became an apprentice to archaeologist Mark Harrington. His reputation grew and he became known as an authority on the Seneca culture; becoming officially recognized as Seneca in 1903 during a ceremony which gave him the name Gáwasowaneh or Big Snow Snake. After working as an ethnologist for the New York State Library in 1904, Arthur became the first full-time archaeologist at the New York State Museum in 1906, serving until 1925. In 1911 Parker notably aided in the founding of the Society for American Indians (SAI). He married Beulah Tahamont, an Abenaki of the Eastern Algonquian, in 1904, whom he had two children with and later divorced, then married Anna Theresa Cooke in 1914, whom he had one child with. Throughout his career he wrote many books and did scholarly research and published Museum Bulletins and articles on the history and culture of Native Americans, with a focus on the Seneca and Iroquois. He was also a consultant on Indian affairs to several Presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, and Coolidge. After working at the New York State Museum, he became director of the Rochester Museum in 1925. He also served from 1935 to 1936 as the Society for American Archaeology’s (SAA) first president. Throughout the remainder of his career, he received many honors and awards, before he passed away in 1955.

Bertha “Birdie” Parker Cody, also called Yewas, her Seneca name, is considered to be the first female Native American archaeologist and ethnologist in the United States. She was born in 1907 in Chautauqua County, New York, and is of Abenaki and Seneca descent, as Arthur C. Parker and Beulah Tahamont were her parents. Bertha grew up with her mother who was an actor, even acting in some shows herself, after her parents divorced. She married Joseph Pallan in the 1920s and gave birth their daughter Wilma Mae in 1925. She never had formal archaeological training or a university education, but she did go on excavations with her father as a child and, after her split from her abusive husband in 1927, she began to work as a cook and expedition secretary for her uncle Mark Raymond Harrington on archaeological projects. She made an amazing discovery at the Mesa House site in 1929. She excavated, recorded, and photographed a pueblo she named Scorpion Hill, and later published her work and had the recovered artifacts exhibited in the Southwest Museum. In 1930 she made a discovery in Nevada’s Gypsum Cave using her slim hands to reach into crevices. Her method allowed her to recover a skull from an extinct species of giant ground sloth known as Nothrotherium shastense. It not only aided in getting more funding for the expedition, but the discovery also challenged prevailing theories about the occupation of ancient Native Americans in the Americas as the sloth skull was found next to ancient human tools.Bertha ended up marrying James Thurston, a Canadian paleontologist who was brought in to further aid the work at the cave, in 1931, but he passed from a heart attack only a year later. In 1933 she was hired to work as secretary for the Southwest Museum, and she eventually became assistant archaeologist and ethnologist. Bertha began to conduct more ethnographic work into the mid-1930s. She wrote and published many archaeological and ethnological papers throughout her career in the Southwest Museum’s journal, Masterkey, on many topics from Kachina Dolls to her work with Californian Indian Tribes including the Maidu, Yurok, Pomo, and Paiute. She married again in 1936 to actor Espera Oscar de Corti, Iron Eyes Cody. Her daughter passed accidentally in 1942, so Cody left the Southwest Museum where she had been working for many years and shifted towards activism and Hollywood. Along with her husband, she advised Native American programs and films as part of “Ironeyes Enterprise”, worked with him to host a 1950s television program about Native American Folklore, supported the Los Angeles Indian Center, and they also adopted two sons of Maricopa-Dakota heritage, Robert and Arthur. She died at the age of 71 in 1978, but her work in the archaeological field lives on. Not only has she conducted work and made discoveries that have greatly added to our knowledge of the past, but her efforts towards influence in the media and spreading awareness and understanding of Native American culture and history, will forever be remembered and appreciated.

Young archaeologist Margaret Spivey is a member of the Pee Dee Indian Nation of Beaver Creek, an assistant chief of the nation’s Upper Georgia Trail Town, and was a Ph.D. Candidate of archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis in 2015. She has stated, “The reason I’m an archaeologist is because I believe we need more research that shows the complexity of Southeastern Native American groups.” Her dissertation focuses on understanding how Southeastern Native Americans interact with animals, identifying and deciphering carvings of animals, and using both archaeology and ethnology to gather information. Her work could provide new insight into early Native American cultures and social movements in the Southwest. Spivey switched from law to archaeology while attending Harvard University in 2004, seeking to improve public understanding and misconceptions, and influence social and political spheres when it came to the cultural past of Native Americans. She was quoted saying, “I don’t think there is a reason to ignore a Native perspective in favor of an outside perspective when looking at materials deposited by Native Americans. This isn’t me looking at it wrong, this is me looking at it differently.” She hopes that her “long-term research will help us enrich and reclaim some of our cultural practices that were unfortunately lost, we just didn’t catch them in time.” As someone of Native American descent, Spivey’s work and perspectives are crucial, as she contributes new interpretations to research being done and artifacts collected as data is being collected. Rather than having to seek out interpretations from Tribes, she can use connections and her life experiences to contribute greatly to the understanding of past Native American cultures.

Dr. Peter Nelson, a Coast Miwok and a citizen of the Federate Indians of Graton Rancheria in the North Bay, became a tenured assistant professor of environmental science, policy and management, and of ethics studies and UC Berkely, after receiving his Ph.D. in anthropology from the same university in 2017. He believes that more native Americans are being drawn into the field of archaeology as new Indigenous know-how and technology, along with Western science, is “speaking to our preservationist values as Indigenous archaeologists and to the values of tribal communities.” Morino Baca, a current UC Berkely graduate student in public health who has ancestral ties to the Genízaro Indigenous community has stated, “There’s a lot of pain associated with that colonization history, so it’s important for younger people in the community to connect to their roots in a positive way, and to engage with their elders because they’re our libraries, and when they’re gone, that knowledge goes with them.” He has worked in New Mexico at Pueblo de Abiquiú to partner with the Genízaro Indigenous community on a cultural revitalization and infrastructure project. Native scholars like Peter Nelson and Morino Baca are just a few who are leading the charge towards better collaboration with Indigenous tribes to find ways to connect western science to Indigenous science during archaeology programs and excavations.

This National Native American Heritage Month, take time to respectfully visit a reservation or Native American heritage site, attend an educational event at a library or museum, attempt to make traditional Native American dishes for Thanksgiving dinner, read the writings or explore the art of Native American authors and artists, or support Native-owned businesses. At the very least take a moment to reflect on and learn about the history of the Indigenous people of this country and the archaeological efforts that are being undertaken around the states today to expand our knowledge of their culture and heritage.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Resources:

https://nationaltoday.com/american-heritage-month/

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/npscelebrates/native-american-heritage-month.htm

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/parker-arthur-caswell

www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/ethnography/collections/research-and-collections-arthur-c-parker

www.theheroinecollective.com/bertha-cody/

untoldstories.net/1927/08/bertha-birdie-parker-cody-first-female-native-american-archeologist/

https://www.saa.org/career-practice/scholarships-and-grants/native-american-scholarships-fund/arthur-c.-parker-and-bertha-parker-cody

https://www.saa.org/quick-nav/saa-media-room/saa-news/2020/11/16/bertha-parker-cody-award

https://news.ufl.edu/articles/2015/07/native-american-archaeologist-unearths-a-complex-cultural-history-.html

news.berkeley.edu/2021/02/04/indigenous-archaeology-plows-forward-despite-anthropologys-checkered-past/

Celebrating National Native American Heritage Month

During the month of November, we celebrate National Native American Heritage Month, or American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month. This celebration is in honor of the original inhabitants of America. Organizations across the States come together to learn about and commemorate the traditions, languages, contributions, and heritage of Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and other Island communities during November.

Honoring the history of the Indigenous people of this land began in 1900 when Dr. Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca Indian and director of the Museum of Arts and Science in New York, convinced the Boy Scouts of America to observe a day for Native Americans. After this, an American Indian Day was declared in 1916. In 1976, a Native American Awareness Week was declared by Congress, and in 1990 former President George H.W. Bush signed a joint congressional resolution to designate November as National American Indian Heritage Month. Since 1994, other proclamations have been made with variations to the name; Native American Heritage Month and National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month are two. It was former President Barack Obama who named November as National Native American Month, which is how we continue to refer to it as of today.

To honor this month, let’s reflect on some Native American archaeologists who have made incredible contributions to the preservation of this county’s heritage and past. Arthur C. Parker was born in 1881 on the Seneca tribe’s Cattaraugus Reservation in New York. He was descended from a long line of Seneca leaders on his father’s side, however, because Seneca clan member ship is matrilineal and both his grandfather and father married women of European descent, neither his father nor him were considered to be Seneca. His family moved to White Plains, NY in 1892 and graduated from high school in 1897. Although he attended Centenary Collegiate institute in New Jersey and Dickinson Seminary in Pennsylvania, he did not graduate from either. However, he continued to do archaeological work while in college and became an apprentice to archaeologist Mark Harrington. His reputation grew and he became known as an authority on the Seneca culture; becoming officially recognized as Seneca in 1903 during a ceremony which gave him the name Gáwasowaneh or Big Snow Snake. After working as an ethnologist for the New York State Library in 1904, Arthur became the first full-time archaeologist at the New York State Museum in 1906, serving until 1925. In 1911 Parker notably aided in the founding of the Society for American Indians (SAI). He married Beulah Tahamont, an Abenaki of the Eastern Algonquian, in 1904, whom he had two children with and later divorced, then married Anna Theresa Cooke in 1914, whom he had one child with. Throughout his career he wrote many books and did scholarly research and published Museum Bulletins and articles on the history and culture of Native Americans, with a focus on the Seneca and Iroquois. He was also a consultant on Indian affairs to several Presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, and Coolidge. After working at the New York State Museum, he became director of the Rochester Museum in 1925. He also served from 1935 to 1936 as the Society for American Archaeology’s (SAA) first president. Throughout the remainder of his career, he received many honors and awards, before he passed away in 1955.

Bertha “Birdie” Parker Cody, also called Yewas, her Seneca name, is considered to be the first female Native American archaeologist and ethnologist in the United States. She was born in 1907 in Chautauqua County, New York, and is of Abenaki and Seneca descent, as Arthur C. Parker and Beulah Tahamont were her parents. Bertha grew up with her mother who was an actor, even acting in some shows herself, after her parents divorced. She married Joseph Pallan in the 1920s and gave birth their daughter Wilma Mae in 1925. She never had formal archaeological training or a university education, but she did go on excavations with her father as a child and, after her split from her abusive husband in 1927, she began to work as a cook and expedition secretary for her uncle Mark Raymond Harrington on archaeological projects. She made an amazing discovery at the Mesa House site in 1929. She excavated, recorded, and photographed a pueblo she named Scorpion Hill, and later published her work and had the recovered artifacts exhibited in the Southwest Museum. In 1930 she made a discovery in Nevada’s Gypsum Cave using her slim hands to reach into crevices. Her method allowed her to recover a skull from an extinct species of giant ground sloth known as Nothrotherium shastense. It not only aided in getting more funding for the expedition, but the discovery also challenged prevailing theories about the occupation of ancient Native Americans in the Americas as the sloth skull was found next to ancient human tools.Bertha ended up marring James Thurston, a Canadian paleontologist who was brought in to further aid the work at the cave, in 1931, but he passed from a heart attack only a year later. In 1933 she was hired to work as secretary for the Southwest Museum, and she eventually became assistant archaeologist and ethnologist. Bertha began to conduct more ethnographical work into the mid-1930s. She wrote and published many archaeological and ethnological papers throughout her career in the Southwest Museum’s journal, Masterkey, on many topics from Kachina Dolls to her work with Californian Indian Tribes including the Maidu, Yurok, Pomo, and Paiute. She married again in 1936 to actor Espera Oscar de Corti, Iron Eyes Cody. Her daughter passed accidentally in 1942, so Cody left the Southwest Museum where she had been working for many years and shifted towards activism and Hollywood. Along with her husband, she advised Native American programs and films as part of “Ironeyes Enterprise”, worked with him to host a 1950s television program about Native American Folklore, supported the Los Angeles Indian Centre, and they also adopted two sons of Maricopa-Dakota heritage, Robert and Arthur. She died at the age of 71 in 1978, but her work in the archaeological field lives on. Not only has she conducted work and made discoveries that have greatly added to our knowledge of the past, but her efforts towards influence in the media and spreading awareness and understanding of Native American culture and history, will forever be remembered and appreciated.

Young archaeologist Margaret Spivey is a member of the Pee Dee Indian Nation of Beaver Creek, an assistant chief of the nation’s Upper Georgia Trail Town, and was a Ph.D. Candidate of archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis in 2015. She has stated, “The reason I’m an archaeologist is because I believe we need more research that shows the complexity of Southeastern Native American groups.” Her dissertation focuses on understanding how Southeastern Native Americans interact with animals, identifying and deciphering carvings of animals, and using both archaeology and ethnology to gather information. Her work could provide new insight into early Native American cultures and social movements in the Southwest. Spivey switched from law to archaeology while attending Harvard University in 2004, seeking to improve public understanding and misconceptions, and influence social and political spheres when it came to the cultural past of Native Americans. She was quoted saying, “I don’t think there is a reason to ignore a Native perspective in favor of an outside perspective when looking at materials deposited by Native Americans. This isn’t me looking at it wrong, this is me looking at it differently.” She hopes that her “long-term research will help us enrich and reclaim some of our cultural practices that were unfortunately lost, we just didn’t catch them in time.” As someone of Native American descent, Spivey’s work and perspectives are crucial, as she contributes new interpretations to research being done and artifacts collected as data is being collected. Rather than having to seek out interpretations from Tribes, she can use connections and her life experiences to contribute greatly to the understanding of past Native American cultures.

Dr. Peter Nelson, a Coast Miwok and a citizen of the Federate Indians of Graton Rancheria in the North Bay, became a tenured assistant professor of environmental science, policy and management, and of ethics studies and UC Berkely, after receiving his Ph.D. in anthropology from the same university in 2017. He believes that more native Americans are being drawn into the field of archaeology as new Indigenous know-how and technology, along with Western science, is “speaking to our preservationist values as Indigenous archaeologists and to the values of tribal communities.” Morino Baca, a current UC Berkely graduate student in public health who has ancestral ties to the Genízaro Indigenous community has stated, “There’s a lot of pain associated with that colonization history, so it’s important for younger people in the community to connect to their roots in a positive way, and to engage with their elders because they’re our libraries, and when they’re gone, that knowledge goes with them.” He has worked in New Mexico at Pueblo de Abiquiú to partner with the Genízaro Indigenous community on a cultural revitalization and infrastructure project. Native scholars like Peter Nelson and Morino Baca are just a few who are leading the charge towards better collaboration with Indigenous tribes to find ways to connect western science to Indigenous science during archaeology programs and excavations.

This National Native American Heritage Month, take time to respectfully visit a reservation or Native American heritage site, attend an educational event at a library or museum, attempt to make traditional Native American dishes for Thanksgiving dinner, read the writings or explore the art of Native American authors and artists, or support Native-owned businesses. At the very least take a moment to reflect on and learn about the history of the Indigenous people of this country and the archaeological efforts that are being undertaken around the states today to expand our knowledge of their culture and heritage.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Resources:

https://nationaltoday.com/american-heritage-month/

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/npscelebrates/native-american-heritage-month.htm

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/parker-arthur-caswell

www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/ethnography/collections/research-and-collections-arthur-c-parker

www.theheroinecollective.com/bertha-cody/

untoldstories.net/1927/08/bertha-birdie-parker-cody-first-female-native-american-archeologist/

https://www.saa.org/career-practice/scholarships-and-grants/native-american-scholarships-fund/arthur-c.-parker-and-bertha-parker-cody

https://www.saa.org/quick-nav/saa-media-room/saa-news/2020/11/16/bertha-parker-cody-award

https://news.ufl.edu/articles/2015/07/native-american-archaeologist-unearths-a-complex-cultural-history-.html

news.berkeley.edu/2021/02/04/indigenous-archaeology-plows-forward-despite-anthropologys-checkered-past/

The Chickaree Hill Pictograph

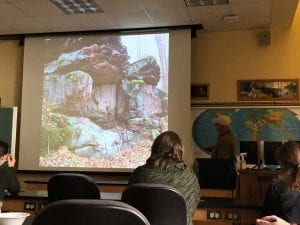

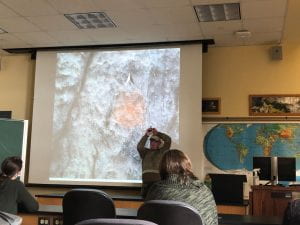

On March 3rd we held our second Graduate Colloquium of the semester! We invited Archaeologist Kenneth Burkett to come in-person and talk to us about the Chickaree Hill Pictograph (36CB8), currently the only known prehistoric pictograph site recorded in Pennsylvania! Kenneth Burkett is the Executive Director of the Jefferson County History Center and Field Associate Archaeologist with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. He recently was awarded the Society for American Archaeology’s (SAA) Crabtree Award, and soon he will be partaking in a 2-year grant study investigating the recorded petroglyph sites in Pennsylvania for their conditions and National Register eligibility status.

The Chickaree pictograph is located on private property in the town of Chickaree in Jackson Township, Cambria County, on a north-sloping upper bench of Laurel Ridge. It was first recorded in 1975 by Dr. Virginia Gerald who was a professor at IUP at the time, and also recorded several other times throughout the eighties and nineties before Burkett began to explore it more in depth in 2017. Advancements in technology and GPS systems have allowed for a more accurate recording of the pictograph’s location.

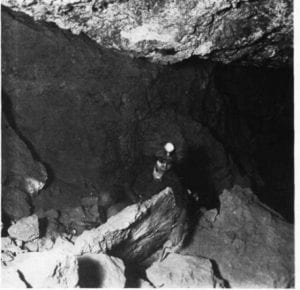

The pictograph itself is located on the ceiling of a small rock overhang facing north, on a large, sandstone rock tor. It does not appear to somewhere where people would have ‘camped out’ as it faces directly into the wind. What appears to be a test unit was opened up sometime in the past directly in front of the overhang, and the soil beneath the overhang was removed too. The place the rock art was drawn in is a well-protected spot, away from the dripline from rain, in a depressed surface away from weather effects, and also difficult to reach without something to elevate one’s height.

The red, circular pictograph is very small, measuring around 14 cm in diameter. It depicts a bird-like figure with orientation of the detached head facing east and the feet facing west, with what has been interpreted as a tail, and with the body and wings spread out as lines forming a horizontal hourglass pattern. Image digitalization aids like DStrech have been useful in making the patterns more visible.

The pictograph was not painted on with something liquid, rather it was applied by abrading something hard over the stone. A hand-held digital microscope and a portable XRF spectrometer were used to learn more about the pigment and how it might have been applied. The red pigment had a high iron content, which was determined to be the mineral hematite. Burkett used experimental archaeology to determine how siderite could have been heated with an open wood burning campfire to be converted into hematite. He placed a sample of siderite in embers and coals for 2 hours. This allowed the siderite, which prior to firing produces a brown color on a streak plate, to convert to hematite, which produced a more reddish-brown color that was consistent with hematite samples from regional prehistoric sites and the Chickaree pictograph itself.

Burkett then discussed similarities with other sites where hematite traces have been found and sites with similar figures, such as the Indian Cave Petroglyphs aka the Harrison County Pictograph site (46HS1) in West Virginia, petroglyphs within the Upper Ohio and Susquehanna river basins, or the Browns Island site (46HK8) in West Virginia. He questioned why there have not been recorded pictographs in Pennsylvania, besides the Chickaree pictograph. He suggested that perhaps they did not survive as the use of hematite and other natural pigments made them easy to be eroded or degraded from the weather and climate, as well as vegetation, which would both obscure and chemically deteriorate the images. Records from the Sullivan Expedition in 1779 stated that Native American iconography was found on trees or logs, which might be connected to the lack of pictographs found in Pennsylvania, as well.

Although Kenneth Burkett concluded that it is impossible to confirm whether the figure is an authentic prehistoric Native American pictograph or not, there are several considerations he pointed out. For one, the pictograph was put in a place that was naturally protected which contributed to its’ survival over the many years. It is also small and concealed, which is opposite of modern graffiti or vandalism which is typically large and visible to attract attention and was not present at the site. The figure itself is stylistically similar to known prehistoric figures including regional components, however the encirclement of the figure is questionable as it is not common within known styles of other Pennsylvania rock art. And finally, the hematite that was used is expected as the correct pigment.

Burkett also discussed other sites that included large rock landforms that show the importance of these landforms, as well as other parts of the landscape, to prehistoric communities. The Parker’s Landing site in Pennsylvania, popular for the 179 petroglyphs carved into a group of rocks by the Allegheny River, was one such site. He also emphasized that although we are archaeologists, we need to look around at sites in different and new perspectives, such as how the sun might hit parts of the site, or even if it is not a place where people might have settled, they still could have buried someone there or created rock art at the site if the area was important to them.

Burkett emphasized that there are most likely more pictographs out there, but indifference and ignorance might play a role in their inability to be found. However, with public education, hopefully more rock art sites can and will be discovered.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Why Do the Leaves Change Color in Fall?

When the days shorten and temperatures fall, the season of autumn begins, most noticeably with the changing color and falling of leaves. As plants stop making what gives them their green color, chlorophyll, due to the colder and darker weather, they instead break it down into smaller molecules, changing the leaves from green into shades of yellow, orange, red, and purple with the carotenoid and anthocyanin pigments accumulating in the leaves in the absences of the chlorophyll. If plants can break down and move the chlorophyll out of the leaves before the leaves fall, they save energy by reabsorbing the molecules that make up chlorophyll so when it is sunnier again, they do not have to start from the beginning to make chlorophyll, as it takes a lot of energy to do so.

While some like to believe that old Jack Frost has a hand in changing leaf colors, long before this legend and modern science, Native American tribes had other explanations for the beautiful fall leaf colors we experience every year. Enjoy reading summaries of some of these ancient Native American legends about why the leaves change color or why they fall (see links below for the full stories!):

While some like to believe that old Jack Frost has a hand in changing leaf colors, long before this legend and modern science, Native American tribes had other explanations for the beautiful fall leaf colors we experience every year. Enjoy reading summaries of some of these ancient Native American legends about why the leaves change color or why they fall (see links below for the full stories!):

The Algonquin believed that there was once a great bear threatening the people of the tribe, by eating their food, destroying their homes, and mauling their women and children. Warriors from several tribes had to come together to hunt it, chasing the bear for months over mountains and seas. One arrow finally pierced the bear but did not kill it. The pain caused the bear to rear up to the heavens where it is still chased by the warriors to this day around the earth. In autumn, the bear rises above the horizon, dripping its blood onto the trees below, causing them to change color.

A similar Haudenosaunee legend also includes a great bear that was stealing the animals the villagers relied on as food. As hunger increased, many parties of warriors went out to kill the bear but failed. Three brothers for three nights had the same recurring dream that they would track and kill the bear. After setting off, they tracked the bears to the end of the earth, following it into the heavens as it leaped from the earth into the sky. The three brothers are still chasing it to this day, and as the bear slows down in the fall to prepare for its winter sleep, the brothers are able to get close enough to injure the bear with arrows, causing the blood to drip down and paint the leaves of fall. Both legends state that the bear reappears in the sky as the Big Dipper, with the warriors still chasing him (they are the handle).

Other similar myths say that celestial hunters do capture the bear each fall, changing the leaves to red from the bears blood, but also as the hunters cook the bear, the fat that spatters out of the great kettle in the sky color the leaves yellow or turn the grass white!

Other similar myths say that celestial hunters do capture the bear each fall, changing the leaves to red from the bears blood, but also as the hunters cook the bear, the fat that spatters out of the great kettle in the sky color the leaves yellow or turn the grass white!

A Lakota legend states that as the winter weather approached, the “grass and flower folk were in sad condition, for they had no protection from the sharp cold.” Then, “he who looks after the things of His creation came to their aid,” by telling the leaves of the trees to fall to the ground to create a warm blanket to protect the roots of the grass and flowers. To repay the trees, he let them have “one last bright array of beauty.” Therefore, every Indian summer, the leaves fall after their display of “farewell colors” to follow their “appointed task-covering the Earth with a thick rug of warmth against the chill of winter.”

A Wyandot (Huron) legend also involves a bear, along with a deer. The selfish Bear who “often made trouble among the Animals of the Great Council” sought out the Deer who had walked over the Rainbow Bridge into the sky land. The Bear said to the Deer, “This sky land is the home of the Little Turtle. Why did you come into this land? Why did you not come to meet us in the Great Council? Why did you not wait until all the Animals could come to live here?” The Deer became angry, believing that only the Wolf could ask these questions. The Deer tried to kill the Bear with his horns, tearing into him, as they fought. The noise from the battle urged the Wolf into the sky to stop the fighting, and both animals fled. The blood of the Bear fell from the Deer’s horns onto the leaves below, changing them to red, yellow, brown, scarlet, and crimson. Each year the leaves take on the multitude of colors, and the Wyandots say “the blood of the Bear has again been thrown down from the sky upon the trees of the Great Island.”

While these are probably only a few of the myths and variations of past reasonings behind the changing of the leaves, they are beautiful stories and a lasting part of Native American history and legends. I hope you enjoyed these small summaries and pause to appreciate the gorgeous, colorful leaves this fall!

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Further Reading:

https://www.britannica.com/story/why-do-leaves-change-colors-in-the-fall

https://askabiologist.asu.edu/questions/why-do-leaves-change-color

https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/WhyTheLeavesFall-Lakota.html

https://www.farmersalmanac.com/weather-ology-why-the-leaves-change-color-14375

https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/WhyTheLeavesHaveManyColorsInAutumn-Wyandot.html

http://www.native-languages.org/cayugastory.htm

https://www.oneidaindiannation.com/autumn-color/

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5277961.pdf

https://iltvignocchi.com/the-mysteries-of-fall-color/

Columbus Day vs. Indigenous Peoples’ Day vs. Italian Heritage Day

With President Biden officially recognizing October 11th as Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we question what may happen to Columbus Day, typically celebrated on the second Monday of October. Several states have been celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day for years in protest of Columbus Day, saying the Christopher Columbus “brought genocide and colonization to communities that had been in the United States for thousands of years.” Columbus Day has been celebrated as a federal holiday since 1968, and as a national holiday from 1934, from the belief “that the nation would be honoring the courage and determination which enabled generation of immigrants from many nations to find freedom and opportunity in America.”

At a United Nations conference in 1977 idea of an Indigenous Peoples’ Day was first proposed by a delegation of Native nations. In 1990, South Dakota became the first state to observe Native American Day. Columbus Day is a federally recognized holiday, and Indigenous Peoples’ Day is not, however there is proposed bill from Congress in the works. Although, U.S. cities and states can choose to observe or not to observe federal holidays.

Indigenous people have protested Columbus Day for many years, and favor a complete transformation of the holiday, rather than a separate celebration for both. Many wonder whether this acknowledgement from the President is actually doing enough for the Indigenous, while other see it is a promising beginning. Jonathan Nez, president of the Navajo Nation stated, “transforming Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day will encourage young Navajos to have pride in the place and people they come from and the beauty they hold within.” While the proclamation does not address issues Indigenous people face with land, water, or female disappearances, some believe that it will help bring awareness to these problems.

Many Italians support Columbus Day and others have called for an Italian Heritage Day, to still allows them to celebrate their heritage. After an 1891 lynching of 11 Italians in New Orleans, many Columbus statues were erected. The president of the National Italian American Foundation stated, “Columbus represented their assimilation into the American fabric and into the American dream.” He believes that Indigenous Peoples’ Day should not “come at the expense of a day that is significant for millions of Italian-Americans” and that the Indigenous are still worthy of their own holiday to “celebrate their contributions to America.”

Some have taken to calling this day of the year both Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Italian Heritage Day. Festivities across the U.S. today still include celebrations for all three titles.

What do you think?

Do you think Columbus Day should be forgotten, despite its intention towards “commemorating the country’s spirit of exploration and honoring Italian-Americans?” Should all three titles be used and celebrated on the same day? Will Indigenous Peoples’ Day increase advocacy toward Indigenous efforts?

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Further Reading:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/us/indigenous-peoples-day.html

https://www.wsj.com/articles/columbus-day-indigenious-peoples-day-what-to-know-11633787027#:~:text=When%20Congress%20officially%20made%20Columbus,to%20the%20Congressional%20Research%20Service.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/10/08/a-proclamation-indigenous-peoples-day-2021/

https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/11/us/indigenous-peoples-day-2021-states-trnd/index.html

https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/informational/columbus-day-myths

Suffrage and Haudenosaunee

Illustration titled “Haudenosaunee” by Jessica Bogac-Moore. Source: https://www.yesmagazine.org/

This year marks the 100-year anniversary of the 19th Amendment which granted women the right to vote. When we study the women’s suffrage movement, the focus tends to be on the Seneca Falls Convention and three main activists: Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. However, history rarely discusses the women of the Haudenosaunee women who inspired these three incredible women. Since the creation of the United States of America, men have been the center of attention. They were given the right to vote, create laws, manage money, and had complete control over everything his wife and daughters “owned”. However, not all governmental systems were like this. The Haudenosaunee of New York, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy, was a democracy (possibly the world’s oldest still in existence) which was based on a matriarchal system. Women were not only included in conferences, had ownership of possessions, and could vote on matters, but they also had great authority and could even dismiss clan leaders.

Cady Stanton lived in Seneca, NY and had close contact with members of the Haudenosaunee and saw first-hand a better life for women. These interactions greatly impacted her view on the world, and she wrote many of her impressions of the Haudenosaunee women in the National Bulletin. Mott also spent time discussion politics and women’s roles in government

Elizabeth Cady Stanton one of the major activists of the suffrage movement

with these women. Gage admired the equality among men and women of the nation. To these three women, and the rest of the women who follow the very male-centered American cultural system, this way of life probably seems like heaven on Earth. Haudenosaunee women could divorce their husbands with ease and keep all their possessions and children. While in the event of an unlikely divorce, the American woman was left with nothing. American women did not have money, possessions, agency, or control over their physical being. They were little more than child baring objects for men to control. Wedding vows included a statement that the women would “obey” her husband, a statement which Cady Stanton omitted from her vows. Men were allowed to beat their wives, and rape or sexual assault did not exist within a marriage. Among all these problems, there was one overarching issue that needed to be addressed. In order to change or create laws to improve women’s lives, men had to take action. Not only were women forced to rely on men in their daily lives, but they also had to rely on them to better their stations. This was not so for the women of the Haudenosaunee. Clan mothers had the authority to take away male authority and change clan leadership. They were consulted at every conference, treaty meeting, and any other major political event. This female presence often made the American male representatives rather uncomfortable.

It is unfortunate that many of these First Nation women are nameless and not mentioned in history books. This nation had democracy and gender equality before the United States even existed. We as people who live under the US Constitution, owe our democracy to these democracy First Nations and we as women owe our rights and ability to vote to those women who through living their lives, inspired other women to make a change. Other cultures can offer so much information that can change the way someone looks at their own culture. Just like Cady Stanton, Gage, and Mott were inspired by the Haudenosaunee women, we can be inspired by many other cultures from around the world. It is important to consider other ways of life and view them not as an “other” but as something to seek new experiences from. Maybe we live better lives if we take a little outside inspiration.

It is unfortunate that many of these First Nation women are nameless and not mentioned in history books. This nation had democracy and gender equality before the United States even existed. We as people who live under the US Constitution, owe our democracy to these democracy First Nations and we as women owe our rights and ability to vote to those women who through living their lives, inspired other women to make a change. Other cultures can offer so much information that can change the way someone looks at their own culture. Just like Cady Stanton, Gage, and Mott were inspired by the Haudenosaunee women, we can be inspired by many other cultures from around the world. It is important to consider other ways of life and view them not as an “other” but as something to seek new experiences from. Maybe we live better lives if we take a little outside inspiration.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Sources: Yes Magazine and http://www.suffragettes2020.com/resources/native-american-and-american-indians

Thanks for Cooking!

Happy Thanksgiving! Everyone has their traditional dishes that must be present at every Thanksgiving meal. Often this is a turkey, green bean casserole, mash potatoes, and stuffing/dressing. Here are some other recipes you might want to consider adding to the table. These are precontact style dishes that can be made using foods that were present in the country before Europeans arrived. More recipes can be found at https://www.firstnations.org/knowledge-center/recipes/. The First Nations Development Institute collected traditional recipes through the Native Agriculture and Food Systems Initiative in partnership with USDA’s Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) to not only preserve these traditional foods but also promote healthy eating and sovereignty. Many tribes are beginning to plant traditional foods on their own lands and providing those foods to their families and communities, making them more independent from the highly capitalistic food industry.

Dry Meat Soup

Ingredients:

Potatoes or Hominy

Salt Pork

Water

Directions:

Boil water in a large saucepan, add the dry meat. This process will take a while as you need to get the dry meat soft. It may take three or four hours. Water can be boiled over a stove, fire, or with heated rocks. During this process, you can change the water out. Once the dried meat is soft, add the potatoes or hominy and salt pork. At this point, you do not want to change the water because this is where you capture all of the flavor. Bring the soup to a boil then turn to medium heat until remaining ingredients are cooked through.

Berry Pudding

Ingredients:

Berries

Water

Flour

Sugar

Directions:

Boil berries in a large saucepan, the water should be a couple of inches above the berries. Boil approximately 10 minutes. Strain berry juice and save. Mash the berries to release the juice. Set aside the berries. Mix enough flour and water to make a thick mixture but not a paste. Using the same boiling pan, pour masked berries and less than half of the saved berry juice back in the pan. Heat at medium-high, slowly pouring the flour mixture in the pan. Keep stirring. If liquid gets thick, pour more berry juice, but not too much. Keep stirring the pudding until it comes to a boil; immediately remove from the stove, there should be some juice left. After the pudding cools, add sugar to taste. Do not leave pudding cooking, it needs to be kept stirred.

More recipes from Native American chefs can be found here in the Smithsonian Magazine.

Hope you have a wonderful and safe Thanksgiving. Thank you for your support and reading these posts.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

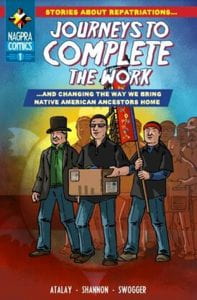

Happy 30th Birthday NAGPRA!

Written by Gage Heuy

This week marked a major anniversary for archaeologists and the Tribal Nations whom they work with: the 30th anniversary of the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Starting November 16th, 1990, the world of cultural resource management would forever be changed with the forging of new relationships between Native Americans,

museums, archaeologists, and federal agencies. NAGPRA ensures that human remains, grave goods, and other objects of cultural patrimony (defined in the act as “an object having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than property owned by an individual) (NAGPRA Sec. 3001.) found on federal land or residing within federally funded institutions is repatriated to the Tribal Nation or Organization whose members or ancestors are associated with those remains or cultural items. In fact, this law goes even further to clearly state that the lineal descendants of those ancestors or the Tribal Nation associated with those remains or sacred objects are the rightful owners of any human remains, funerary objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. This is a far cry from the early days of archaeology and museums where the objects found during excavation (regardless of how significant they were to living peoples) belonged to the archaeologist who “discovered” them, or the museums who accessioned them into their collections. In the 30 years since NAGPRA became law, the culture within archaeology has taken a dramatic shift, where more and more professionals within academia, museums, and CRM understand the necessity to respect the ancestors and material culture of Native Americans and are committed to working alongside their governments to ensure that this respect informs every step of the NAGPRA process.

museums, archaeologists, and federal agencies. NAGPRA ensures that human remains, grave goods, and other objects of cultural patrimony (defined in the act as “an object having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than property owned by an individual) (NAGPRA Sec. 3001.) found on federal land or residing within federally funded institutions is repatriated to the Tribal Nation or Organization whose members or ancestors are associated with those remains or cultural items. In fact, this law goes even further to clearly state that the lineal descendants of those ancestors or the Tribal Nation associated with those remains or sacred objects are the rightful owners of any human remains, funerary objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. This is a far cry from the early days of archaeology and museums where the objects found during excavation (regardless of how significant they were to living peoples) belonged to the archaeologist who “discovered” them, or the museums who accessioned them into their collections. In the 30 years since NAGPRA became law, the culture within archaeology has taken a dramatic shift, where more and more professionals within academia, museums, and CRM understand the necessity to respect the ancestors and material culture of Native Americans and are committed to working alongside their governments to ensure that this respect informs every step of the NAGPRA process.

The law outlines a process that requires special cooperation between archaeologists and Indigenous communities that ultimately results in repatriation, or a “giving back” of the ancestors or sacred objects. Repatriation looks different on a case to case basis, but essentially, any institution who  receives federal funding (be that museums, universities, etc.) must compile an Inventory of Indigenous human remains and associated funerary objects; identifying any ancestors or associated funerary objects present within their collections and formally reaching out to the Federally Recognized Tribe or Nation with a possible cultural or geographic relation to the individual whose remains are held by the agency. Once face to face consultation is initiated in accordance with the principles of Government to Government consultation, a determination is made on whether or not the individual(s) held in the collections can be culturally affiliated, meaning that a relationship of shared identity can be traced from the deceased individual’s culture and a present-day Federally Recognized Tribe or Native Hawaiian Organization (NHO).

receives federal funding (be that museums, universities, etc.) must compile an Inventory of Indigenous human remains and associated funerary objects; identifying any ancestors or associated funerary objects present within their collections and formally reaching out to the Federally Recognized Tribe or Nation with a possible cultural or geographic relation to the individual whose remains are held by the agency. Once face to face consultation is initiated in accordance with the principles of Government to Government consultation, a determination is made on whether or not the individual(s) held in the collections can be culturally affiliated, meaning that a relationship of shared identity can be traced from the deceased individual’s culture and a present-day Federally Recognized Tribe or Native Hawaiian Organization (NHO).

In a case where association of an individual cannot be linked to a Federally Recognized Tribe, those individuals and any items that they were interred with are referred to as “Culturally Unidentifiable”. A museum or federal agency who currently houses “Culturally Unidentifiable” ancestors and funerary objects must offer to transfer those remains and objects to either the Federally Recognized Tribes whose present Tribal lands the individual was buried and subsequently removed from or the Tribe(s) whose ancestral lands the individual was discovered on. The Summary process is similar, though instead of specific ancestral individuals and associated funerary objects, this process is concerned with unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and other objects of cultural patrimony. A summary is simply a general description of what objects in those categories are present within the holdings or collections of museums or Federal agencies that serves as an invitation to begin a consultation process with the Federally Recognized Native American Tribes, Native Alaskan Villages, or Native Hawaiian Organizations. Lastly, NAGPRA prohibits the removal of Indigenous remains or culturally sensitive items on Federally or Tribally owned lands without first receiving a permit issued under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA). Once the permit is received, consultation is still required to ensure that the remains or artifacts are handled properly and eventually repatriated. The law also outlines a process that archaeologists and CRM professionals must follow in the event of an inadvertent discovery of human remains. It states that the appropriate Federal agency or Tribal official must be contacted immediately and the project that disturbed the remains or objects is halted until consultation takes place in order to develop a plan for the safety and proper disposition of the individual.

Repatriation and burial service. Source: nps.gov

While NAGPRA is seen as a great improvement in the relationships between Federal agencies, archaeologists, and Indigenous peoples, it hasn’t always been viewed favorably in the three decades since it was passed. One critique of NAGPRA that was very common throughout the 1990s and 2000s is that this law undermines scientific authority and is a determent to archaeological and bioarcheological research because it removes artifacts and remains for the realm of research. This critique is not entirely well founded and stems from problematic ideas about archaeologists’ role in the removal and study of Indigenous bodies and cultural goods. Archaeologists and anthropologists have a long history of claiming ownership over Indigenous remains and the material culture that was interred with the deceased. NAGPRA reasserts Indigenous sovereignty over their ancestors’ remains and possessions, and from the perspective of some (see Gonzalez and Marek-Martinez 2015), the NAGPRA process actually provides an opportunity for archaeologists to develop new kinds of research questions and to work alongside Indigenous peoples as that research is developed.

Repatriation Comic Link here

While archaeologists seem to have finally come around to embracing this re-assertion of Indigenous sovereignty, there are still hundreds of thousands of Native ancestors whose remains are currently held by Federally funded museums, universities, and agencies. Nationwide, it is assumed that 60% (around 120,000 individuals) of the ancestors held by universities, museums, and other institutions have not been returned to Tribes through the NAGPRA process. This could be due to a number of reasons, but regardless of the reasoning, it is clear that much more work is to be done in returning ancestors to Tribal Nations and respecting the sovereignty of Native Americans. I firmly believe that the next 30 years of NAGPRA will see an increase in awareness, respect, and accountability on the part of settler archaeologists who are finally coming around to understanding our role in the ongoing colonization of the Indigenous peoples of this continent.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

For more information about NAGPRA see:

Carrying our Ancestors Home, Association for Indian Affairs, 30 Years of NAGPRA Discussion w/ ArchyFantasies and Dr. Krystiana Krupa, The National NAGPRA Program

Preserving Heritage

Native American heritage is an important part of the history and culture of the Americas. Like many other descendant community cultures, many of the traditions and ways of life are at risk of dying out. Many organizations, both within the government and provide non-profit organizations, strive to work with tribes, craftspeople, and the public to ensure the survival of traditions and to education people about the importance of such heritages. Within the government, the leading body in preservation is the

from doi.org Indian Arts and Crafts Board

National Park Service. The National Historic Preservation Act mandates that the Secretary of the Interior (through the NPS) establish a National Tribal Preservation Program. The program works to preserve traditions and resources important to Native American tribes, Native Hawaiian organizations, and Native Alaskan communities. One of the main programs it offers is the Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPO) program which is specific to federally recognized tribes. These tribes are able to submit forms to petition for the assignment of a THPO who acts in the same manner as the State Historic Preservation Officer but is in charge of tribal resources rather than the entire state’s resources. Once a THPO is granted the tribe is then eligible to receive Historic Preservation Fund (HPF) grants which provide funding for locating and identifying cultural resources, preserving historic structures listed in the National Register, creating comprehensive preservation plans, documenting oral histories and traditions, and building a Historic Preservation Program. The THPO program was first initiated in 1990 and in 1996 twelve tribes were approved to assign a THPO. In 2018 180 THPOs have been approved. Pennsylvania’s Delaware tribe is not among those recognized or approved so the THPO officer responsible for this state’s First Nation resources is from the Seneca Nation in New York. The issue of federal recognition was discussed in a previous post which can be accessed here.

Because many tribes are not federally recognized, such as the Delaware from Pennsylvania, and are not eligible for a THPO and federal support, more localized organizations take on the responsibility of preserving traditions and educating the public about their culture. One such organization is the Native American Heritage Programs group focusing on celebrating the Lenape culture. The group provides educational programs and tools to schools, libraries, historical societies, and other groups. They have a traveling educational group that will bring the culture to the students. This in person experience tends to make more of an impact on students (child and adult alike) than do reading about the culture. One slightly less localized program is PBS Utah’s Native American Heritage Collection which has created many documentaries on the First Nation tribes located in Utah. These documentaries focus on giving a voice to the people and tackle not only culture but also topics such as Native American boarding schools, veteran treatment, and the Bears Ears Monument debate. These documentaries can be found here.

Programs such as these are important to preserving the heritage that this month celebrates. Not only is it important just to record the oral histories, traditions, craftmanship, and culture of descendant communities, but it is also important to educate the public about them and their significance. It is quite likely that most people do not realize that these ways of life are in danger of becoming extinct or even that modern day tribes still retain traditions dating back hundreds or thousands of years. Unfortunately, government programs focus almost solely on federally recognized tribes with little regard for the unrecognized tribes. Thankfully, many other organizations have been trying to record all of the traditions from every group possible. The more the public is aware of the need for preservation, the more likely they are to help in that preservation.

Sources: https://lenapeprograms.info/about/, https://www.nps.gov/history/tribes/Tribal_Historic_Preservation_Officers_Program.htm

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram