On March 3rd we held our second Graduate Colloquium of the semester! We invited Archaeologist Kenneth Burkett to come in-person and talk to us about the Chickaree Hill Pictograph (36CB8), currently the only known prehistoric pictograph site recorded in Pennsylvania! Kenneth Burkett is the Executive Director of the Jefferson County History Center and Field Associate Archaeologist with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. He recently was awarded the Society for American Archaeology’s (SAA) Crabtree Award, and soon he will be partaking in a 2-year grant study investigating the recorded petroglyph sites in Pennsylvania for their conditions and National Register eligibility status.

The Chickaree pictograph is located on private property in the town of Chickaree in Jackson Township, Cambria County, on a north-sloping upper bench of Laurel Ridge. It was first recorded in 1975 by Dr. Virginia Gerald who was a professor at IUP at the time, and also recorded several other times throughout the eighties and nineties before Burkett began to explore it more in depth in 2017. Advancements in technology and GPS systems have allowed for a more accurate recording of the pictograph’s location.

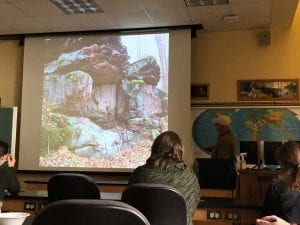

The pictograph itself is located on the ceiling of a small rock overhang facing north, on a large, sandstone rock tor. It does not appear to somewhere where people would have ‘camped out’ as it faces directly into the wind. What appears to be a test unit was opened up sometime in the past directly in front of the overhang, and the soil beneath the overhang was removed too. The place the rock art was drawn in is a well-protected spot, away from the dripline from rain, in a depressed surface away from weather effects, and also difficult to reach without something to elevate one’s height.

The red, circular pictograph is very small, measuring around 14 cm in diameter. It depicts a bird-like figure with orientation of the detached head facing east and the feet facing west, with what has been interpreted as a tail, and with the body and wings spread out as lines forming a horizontal hourglass pattern. Image digitalization aids like DStrech have been useful in making the patterns more visible.

The pictograph was not painted on with something liquid, rather it was applied by abrading something hard over the stone. A hand-held digital microscope and a portable XRF spectrometer were used to learn more about the pigment and how it might have been applied. The red pigment had a high iron content, which was determined to be the mineral hematite. Burkett used experimental archaeology to determine how siderite could have been heated with an open wood burning campfire to be converted into hematite. He placed a sample of siderite in embers and coals for 2 hours. This allowed the siderite, which prior to firing produces a brown color on a streak plate, to convert to hematite, which produced a more reddish-brown color that was consistent with hematite samples from regional prehistoric sites and the Chickaree pictograph itself.

Burkett then discussed similarities with other sites where hematite traces have been found and sites with similar figures, such as the Indian Cave Petroglyphs aka the Harrison County Pictograph site (46HS1) in West Virginia, petroglyphs within the Upper Ohio and Susquehanna river basins, or the Browns Island site (46HK8) in West Virginia. He questioned why there have not been recorded pictographs in Pennsylvania, besides the Chickaree pictograph. He suggested that perhaps they did not survive as the use of hematite and other natural pigments made them easy to be eroded or degraded from the weather and climate, as well as vegetation, which would both obscure and chemically deteriorate the images. Records from the Sullivan Expedition in 1779 stated that Native American iconography was found on trees or logs, which might be connected to the lack of pictographs found in Pennsylvania, as well.

Although Kenneth Burkett concluded that it is impossible to confirm whether the figure is an authentic prehistoric Native American pictograph or not, there are several considerations he pointed out. For one, the pictograph was put in a place that was naturally protected which contributed to its’ survival over the many years. It is also small and concealed, which is opposite of modern graffiti or vandalism which is typically large and visible to attract attention and was not present at the site. The figure itself is stylistically similar to known prehistoric figures including regional components, however the encirclement of the figure is questionable as it is not common within known styles of other Pennsylvania rock art. And finally, the hematite that was used is expected as the correct pigment.

Burkett also discussed other sites that included large rock landforms that show the importance of these landforms, as well as other parts of the landscape, to prehistoric communities. The Parker’s Landing site in Pennsylvania, popular for the 179 petroglyphs carved into a group of rocks by the Allegheny River, was one such site. He also emphasized that although we are archaeologists, we need to look around at sites in different and new perspectives, such as how the sun might hit parts of the site, or even if it is not a place where people might have settled, they still could have buried someone there or created rock art at the site if the area was important to them.

Burkett emphasized that there are most likely more pictographs out there, but indifference and ignorance might play a role in their inability to be found. However, with public education, hopefully more rock art sites can and will be discovered.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram