By Sarah W. Neusius

More than a decade and a half ago, then Director of IUP Archaeological Services, Dr. Beverly Chiarulli, and I observed that Pennsylvania archaeologists sometimes referred to the area around Indiana as vacant during the last centuries of the Pre-Columbian period. The dominant cultural tradition archaeologists recognize for southwestern Pennsylvania after AD 1000 is the Monongahela tradition, and while there had been a lot of research on Monongahela sites in counties to our south and west, there wasn’t much known about the inhabitants of our immediate area. Thus it was fairly logical to assume that this was a cultural backwater or even vacant at this time. The tradition that our area was used only for hunting early in the Historic era also supported this idea.

However, based on work that Dr. Chiarulli had been doing with the Pennsylvania state site files and predictive modeling, she knew that there was a relatively large numbers of Late Prehistoric or Late Woodland village sites recorded – at least 30 apparent villages for the Conemaugh-Blacklick and Crooked Creek watersheds alone. This went against the assumption that this part of the state, which can be called central western Pennsylvania, was a sort of cultural backwater and even uninhabited after AD 1000. The problem obviously seemed to be that most of these sites had not received much professional attention; very little was known about them, and even less was included in the regional literature.

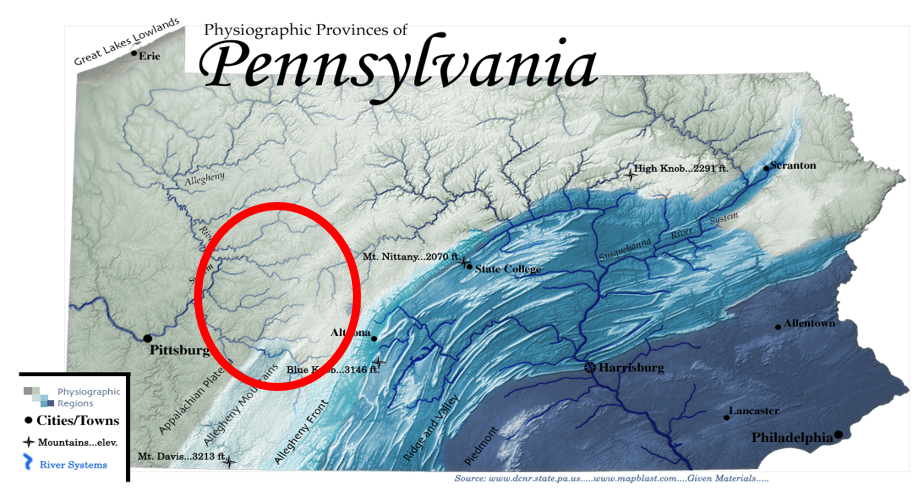

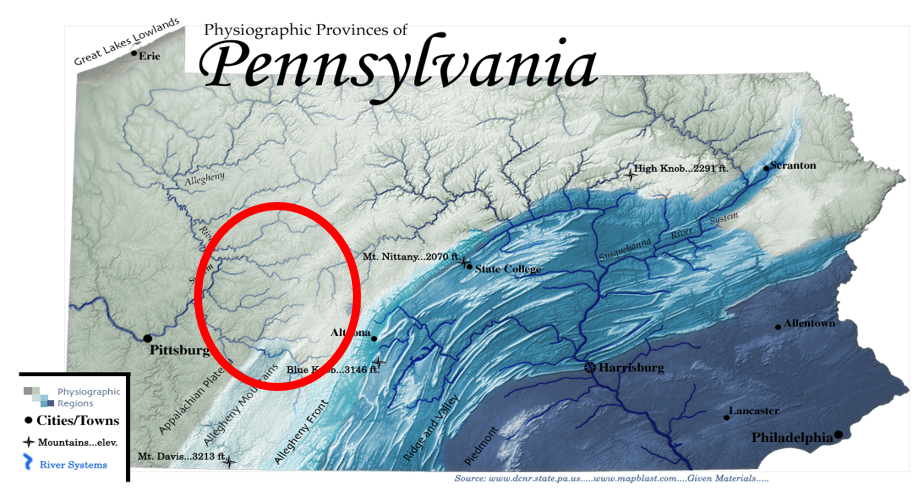

Red circle outlines the approximate area of interest for the IUP Late Prehistoric.

The IUP Late Prehistoric Project or LPP, was initiated because of these observations, and it continues today because there is still a lot to learn. It only made sense for IUP archaeologists to explore these recorded sites. They are accessible, potentially well preserved, and likely to add significantly to Pennsylvania archaeology. Since approximately 2000, many IUP faculty and students have focused on learning more about sites in the Conemaugh-Blacklick, Crooked Creek, and Loyalhanna drainages of west-central Pennsylvania dating between approximately AD 1000 and 1600. We have employed field schools, student projects, and MA thesis research to learn about these sites. We also have been incorporating sites studied by IUP archaeologists during the 1970s and early 1980s as several of these are LPP villages that haven’t been thoroughly analyzed and written up. Occasionally the work of IUP Archaeological Services has dovetailed with these efforts as well. Dr. Chiarulli, myself, and Dr. Phil Neusius all have participated in excavations and analyses related to this project. With this summer’s field school at the Squirrel Hill site, Dr. Homsey-Messer and Dr. Chadwick also have become part of this initiative. Together, we are adding significantly to archaeological knowledge of the distribution of people during the Late Prehistoric. Some of our information has been shared through meetings presentations, Masters theses (available through the IUP website) and publications. However, there is a great deal more to be written about, and I am currently working hardest on this aspect of the project.

Before explaining a little bit more about the areas of research that have been pursued, I’d like to clarify the use of the term Late Prehistoric. You may have learned that Late Woodland is the name archaeologists use for the end of the Pre-Columbian times in places like Pennsylvania. In the southern Midwest and Southeast, Late Woodland follows the collapse of Middle Woodland Hopewellian societies by approximately AD 500. It continues in these areas until Missisisppian cultural developments are evident between AD 800 and 1000, when archaeologists designate a Mississippian period continuing until Historic times. Elsewhere evidence of Mississippian tradition societies has not been found by archaeologists, and in the Upper Midwest the Late Woodland often is not seen as ending until European Contact. The situation on the eastern edges of the MIdwest, is a little more complicated. Some archaeological traditions including the Fort Ancient tradition, found mostly in Ohio and West Virginia, and the Monongahela tradition, found mostly in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, often have been designated as Late Prehistoric because of the similarities in dating, presumed interactions with Mississippian societies, and similar material culture (e.g. shell-tempererd pottery and communities with central plazas). Thus, it has been more common to call Monongahela tradition sites Late Prehistoric than Late Woodland. Because central Western Pennsylvania encompasses the northern edges of the Monongahela area and some of our sites can be considered Monongahela, we use the term Late Prehistoric rather than Late Woodland for our project.

One of the highlights of the LPP is the development of an extensive catalogue of radiocarbon dates for the sites in our area. When we began this project in 2000, there were not any radiocarbon dates for the LPP sites and villages. Now there are approximately 85 dates some of which are standard radiometric dates, but the majority of which are AMS dates. These latter Accelerator Mass Spectrometry dates now are the preferred radiocarbon dating method because they require less carbonized materials – as little as 20 mg as opposed to the 10 grams required for wood charcoal by standard radiometric dating methods. This means less material is destroyed in the dating process. Another advantage of AMS dating is that the dates often are more precise; they usually have date ranges within 50 years plus or minus from the mean. In any case in just over a decade and half we have greatly increased our ability to understand the chronology of the Late Prehistoric in our area. Most importantly we have been able to show that occupation of these watersheds spans the entire Late Prehistoric as shown in this chart of some of the dates we have obtained for Conemaugh-Blacklick Watershed sites. Note the AD years from AD 100 to almost AD 1800 in calibrated years across the bottom of the chart. These dates certainly span the Late

Radiocarbon date ranges for some Conemaugh-Blacklick watershed sites.

Prehistoric period from AD 1000-AD 1600. Calibrated years are approximations of calendar years based on adjusting radiocarbon years to known fluctuations in the amounts of carbon in the atmosphere. This figure gives you date ranges at both the 68% confidence interval (dark brackets) and the 95% confidence interval (gray lines) so that the earliest date on this chart has a 95% probablity of falling between approximately AD 650 and AD 1175 and a 68% probabilty of falling between approximately AD 775 and AD 1025 while the most recent date falls between ca. AD 1290 and AD 1780 at the 95% confidence interval and between ca. AD1400 and AD 1650 at the 68% confidence interval.

Another highlight of the LPP has been our identification of a possible cultural boundary between Mononghaela people and their neighbors to the north. Although many of our sites can be assigned to the Johnston Phase of the Monongahela tradition, others, especially those in the Crooked Creek drainage, appear not to truly be Monongahela, and to exhibit closer ties to Late Woodland groups living in northwestern Pennsylvania. These more northerly people seem to have made different ceramics, especially pots made with limestone temper as opposed to shell temper, as well as possibly to have less organized villages. Recently, and in part due to LPP research, the Crooked Creek Complex has been defined to encompass these sites, but there is a lot more that needs to be learned about these sites and those still further north, as much of the data remains in the hands of avocational archaeologists, and has only been partially studied. Important Crooked Creek Complex sites for which IUP has collections are Mary Rinn (36IN29) and Fleming (36IN26). This year an undergraduate honors thesis will be exploring the Mary Rinn site through geophysics as well.

Contrasting ceramics from the Johnston site (Johnston Phase Monongahela) and the Mary Rinn site (Crooked Creek Complex).

A major undertaking of LPP archaeologists has been re-investigation of the Johnston site (36IN2) , located near Blairsville. This large village site is the type site for Johnston Phase Monongahela (AD 1450-1590), and it may be the second largest known Monongahela village. It was excavated in the 1950s by archaeologists from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh before the completion of the Conemaugh lock and dam. Today it is buried beneath flood sediments of the Conemaugh River Lake on land belonging to the US Army Corps of Engineers. By conducting five IUP archaeological field schools at Johnston beginning in 2006, we have added greatly to the information on this site, demonstrating that it is a multi-component site of some complexity, and we have called the definition of the Johnston Phase itself into question. Although, there is still much more potential for research at Johnston, we have obtained more than 40 radiocarbon dates from this site alone and recovered hundreds of thousands of artifacts. As a result, we are pausing in our excavations to take more thorough stock of what we have been learning. Graduate and undergraduate theses have now focused on ceramics, bone tools, faunal remains, lithics, FCR, and botanical remains from the Johnston site. Three others still in progress are exploring the site’s geomorphology, the spatial distribution of materials, and micro-artifactual evidence, and I am immersed in the analysis and write-up of our findings as well.

Excavations in progress at the Johnston site, 2012 (left), 2010 (right).

These are only a few highlights of the IUP Late Prehistoric Project, which has been employing excavation, geophysical survey, as well as faunal, botanical, lithic and ceramic analyses to gather evidence concerning the forgotten or porrly understood Late Prehistoric villages of central western Pennsylvania. As a result these villages are forgotten no more. If you are an IUP graduate or undergraduate student, you should consider joining other IUP archaeologists and getting involved with some aspect of this project. There are many worthwhile projects that you might undertake, and I will be happy to explore possibilities with you. Whether or not the LPP is your cup of tea, it is an important part of the archaeology IUP is doing, and you can anticipate hearing more about it in the future.