During the month of November, we celebrate National Native American Heritage Month, or American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month. This celebration is in honor of the original inhabitants of America. Organizations across the States come together to learn about and commemorate the traditions, languages, contributions, and heritage of Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and other Island communities during November. This post was originally written by former Public Archaeology Graduate Assistant Bridget Roddy two years ago, and the piece is so well written, I did not want to attempt improving upon it.

Honoring the history of the Indigenous people of this land began in 1900 when Dr. Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca Indian and director of the Museum of Arts and Science in New York, convinced the Boy Scouts of America to observe a day for Native Americans. After this, an American Indian Day was declared in 1916. In 1976, a Native American Awareness Week was declared by Congress, and in 1990 former President George H.W. Bush signed a joint congressional resolution to designate November as National American Indian Heritage Month. Since 1994, other proclamations have been made with variations to the name; Native American Heritage Month and National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month are two. It was former President Barack Obama who named November as National Native American Month, which is how we continue to refer to it as of today.

Arthur C. Parker, 1918 (Buffalo Historical Society)

To honor this month, let’s reflect on some Native American archaeologists who have made incredible contributions to the preservation of this county’s heritage and past. Arthur C. Parker was born in 1881 on the Seneca tribe’s Cattaraugus Reservation in New York. He was descended from a long line of Seneca leaders on his father’s side, however, because Seneca clan member ship is matrilineal and both his grandfather and father married women of European descent, neither his father nor him were considered to be Seneca. His family moved to White Plains, NY in 1892 and graduated from high school in 1897. Although he attended Centenary Collegiate institute in New Jersey and Dickinson Seminary in Pennsylvania, he did not graduate from either. However, he continued to do archaeological work while in college and became an apprentice to archaeologist Mark Harrington. His reputation grew and he became known as an authority on the Seneca culture; becoming officially recognized as Seneca in 1903 during a ceremony which gave him the name Gáwasowaneh or Big Snow Snake. After working as an ethnologist for the New York State Library in 1904, Arthur became the first full-time archaeologist at the New York State Museum in 1906, serving until 1925. In 1911 Parker notably aided in the founding of the Society for American Indians (SAI). He married Beulah Tahamont, an Abenaki of the Eastern Algonquian, in 1904, whom he had two children with and later divorced, then married Anna Theresa Cooke in 1914, whom he had one child with. Throughout his career he wrote many books and did scholarly research and published Museum Bulletins and articles on the history and culture of Native Americans, with a focus on the Seneca and Iroquois. He was also a consultant on Indian affairs to several Presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, and Coolidge. After working at the New York State Museum, he became director of the Rochester Museum in 1925. He also served from 1935 to 1936 as the Society for American Archaeology’s (SAA) first president. Throughout the remainder of his career, he received many honors and awards, before he passed away in 1955.

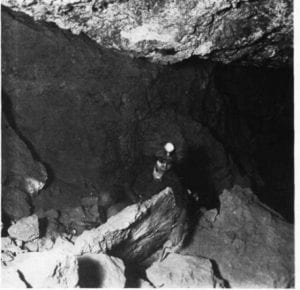

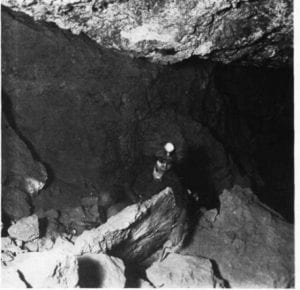

Bertha Parker Pallan [Cody] (Smithsonian Institution Archives)

Bertha “Birdie” Parker Cody, also called Yewas, her Seneca name, is considered to be the first female Native American archaeologist and ethnologist in the United States. She was born in 1907 in Chautauqua County, New York, and is of Abenaki and Seneca descent, as Arthur C. Parker and Beulah Tahamont were her parents. Bertha grew up with her mother who was an actor, even acting in some shows herself, after her parents divorced. She married Joseph Pallan in the 1920s and gave birth their daughter Wilma Mae in 1925. She never had formal archaeological training or a university education, but she did go on excavations with her father as a child and, after her split from her abusive husband in 1927, she began to work as a cook and expedition secretary for her uncle Mark Raymond Harrington on archaeological projects. She made an amazing discovery at the Mesa House site in 1929. She excavated, recorded, and photographed a pueblo she named Scorpion Hill, and later published her work and had the recovered artifacts exhibited in the Southwest Museum. In 1930 she made a discovery in Nevada’s Gypsum Cave using her slim hands to reach into crevices. Her method allowed her to recover a skull from an extinct species of giant ground sloth known as

Nothrotherium shastense. It not only aided in getting more funding for the expedition, but the discovery also challenged prevailing theories about the occupation of ancient Native Americans in the Americas as the sloth skull was found next to ancient human tools.

Cody at Gypsum Cave, Nevada (Southwest Museum)

Bertha ended up marrying James Thurston, a Canadian paleontologist who was brought in to further aid the work at the cave, in 1931, but he passed from a heart attack only a year later. In 1933 she was hired to work as secretary for the Southwest Museum, and she eventually became assistant archaeologist and ethnologist. Bertha began to conduct more ethnographic work into the mid-1930s. She wrote and published many archaeological and ethnological papers throughout her career in the Southwest Museum’s journal, Masterkey, on many topics from Kachina Dolls to her work with Californian Indian Tribes including the Maidu, Yurok, Pomo, and Paiute. She married again in 1936 to actor Espera Oscar de Corti, Iron Eyes Cody. Her daughter passed accidentally in 1942, so Cody left the Southwest Museum where she had been working for many years and shifted towards activism and Hollywood. Along with her husband, she advised Native American programs and films as part of “Ironeyes Enterprise”, worked with him to host a 1950s television program about Native American Folklore, supported the Los Angeles Indian Center, and they also adopted two sons of Maricopa-Dakota heritage, Robert and Arthur. She died at the age of 71 in 1978, but her work in the archaeological field lives on. Not only has she conducted work and made discoveries that have greatly added to our knowledge of the past, but her efforts towards influence in the media and spreading awareness and understanding of Native American culture and history, will forever be remembered and appreciated.

Margaret Spivey (Kristen Grace Photography, University of Florida)

Young archaeologist Margaret Spivey is a member of the Pee Dee Indian Nation of Beaver Creek, an assistant chief of the nation’s Upper Georgia Trail Town, and was a Ph.D. Candidate of archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis in 2015. She has stated, “The reason I’m an archaeologist is because I believe we need more research that shows the complexity of Southeastern Native American groups.” Her dissertation focuses on understanding how Southeastern Native Americans interact with animals, identifying and deciphering carvings of animals, and using both archaeology and ethnology to gather information. Her work could provide new insight into early Native American cultures and social movements in the Southwest. Spivey switched from law to archaeology while attending Harvard University in 2004, seeking to improve public understanding and misconceptions, and influence social and political spheres when it came to the cultural past of Native Americans. She was quoted saying, “I don’t think there is a reason to ignore a Native perspective in favor of an outside perspective when looking at materials deposited by Native Americans. This isn’t me looking at it wrong, this is me looking at it differently.” She hopes that her “long-term research will help us enrich and reclaim some of our cultural practices that were unfortunately lost, we just didn’t catch them in time.” As someone of Native American descent, Spivey’s work and perspectives are crucial, as she contributes new interpretations to research being done and artifacts collected as data is being collected. Rather than having to seek out interpretations from Tribes, she can use connections and her life experiences to contribute greatly to the understanding of past Native American cultures.

Morino Baca (photo by Danny Sosa Aguilar)

Dr. Peter Nelson, a Coast Miwok and a citizen of the Federate Indians of Graton Rancheria in the North Bay, became a tenured assistant professor of environmental science, policy and management, and of ethics studies and UC Berkely, after receiving his Ph.D. in anthropology from the same university in 2017. He believes that more native Americans are being drawn into the field of archaeology as new Indigenous know-how and technology, along with Western science, is “speaking to our preservationist values as Indigenous archaeologists and to the values of tribal communities.” Morino Baca, a current UC Berkely graduate student in public health who has ancestral ties to the Genízaro Indigenous community has stated, “There’s a lot of pain associated with that colonization history, so it’s important for younger people in the community to connect to their roots in a positive way, and to engage with their elders because they’re our libraries, and when they’re gone, that knowledge goes with them.” He has worked in New Mexico at Pueblo de Abiquiú to partner with the Genízaro Indigenous community on a cultural revitalization and infrastructure project. Native scholars like Peter Nelson and Morino Baca are just a few who are leading the charge towards better collaboration with Indigenous tribes to find ways to connect western science to Indigenous science during archaeology programs and excavations.

This National Native American Heritage Month, take time to respectfully visit a reservation or Native American heritage site, attend an educational event at a library or museum, attempt to make traditional Native American dishes for Thanksgiving dinner, read the writings or explore the art of Native American authors and artists, or support Native-owned businesses. At the very least take a moment to reflect on and learn about the history of the Indigenous people of this country and the archaeological efforts that are being undertaken around the states today to expand our knowledge of their culture and heritage.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Resources:

https://nationaltoday.com/american-heritage-month/

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/npscelebrates/native-american-heritage-month.htm

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/parker-arthur-caswell

www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/ethnography/collections/research-and-collections-arthur-c-parker

www.theheroinecollective.com/bertha-cody/

untoldstories.net/1927/08/bertha-birdie-parker-cody-first-female-native-american-archeologist/

https://www.saa.org/career-practice/scholarships-and-grants/native-american-scholarships-fund/arthur-c.-parker-and-bertha-parker-cody

https://www.saa.org/quick-nav/saa-media-room/saa-news/2020/11/16/bertha-parker-cody-award

https://news.ufl.edu/articles/2015/07/native-american-archaeologist-unearths-a-complex-cultural-history-.html

news.berkeley.edu/2021/02/04/indigenous-archaeology-plows-forward-despite-anthropologys-checkered-past/