Cemeteries are not just these spooky, misty places where monsters and ghosts hang out. They are also a pumpkin full of information that archaeologists can explore. One of the first things that people tend to think of when discussing archaeology and graves is grave robbing. In the past (Indiana Jones) archaeologists would have been considered grave robbers. Many were sent to collect rare and priceless artifacts by  museums, many of which were either located in graves (grave goods) or in other sacred sites. Graves tend to have the precious metals (Agamemnon’s gold death mask) and intact artifacts that were deliberately placed with the deceased. Nowadays, archaeologists try their best to leave graves undisturbed if they can. Sometimes this is not an option, especially when graveyards are in the path of infrastructure projects. During those cases, archaeologists work with the community and descendants of the deceased to relocate the graves with all the respect that they deserve.

museums, many of which were either located in graves (grave goods) or in other sacred sites. Graves tend to have the precious metals (Agamemnon’s gold death mask) and intact artifacts that were deliberately placed with the deceased. Nowadays, archaeologists try their best to leave graves undisturbed if they can. Sometimes this is not an option, especially when graveyards are in the path of infrastructure projects. During those cases, archaeologists work with the community and descendants of the deceased to relocate the graves with all the respect that they deserve.

Another aspect of graveyard archaeology people tend to think of is that archaeologists uncover unmarked graves from war, Native American and other past and ancient civilizations, very old unrecorded Christian cemeteries, and pyramids.

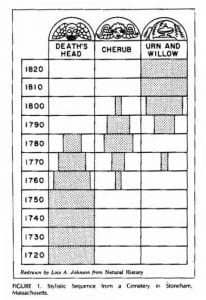

Deetz’s examination of Puritan Gravestone engravings and their frequency over time

While true in many cases the marked more modern-day cemeteries in church yards can offer a lot of information to archaeologists. Much of this information is gathered by means other than excavation. Excavating and analyzing human remains is a very controversial subject that brings into spiritual and moral issues. While human remains can provide plenty of information, there is also plenty lying on the surface in the tombstones, cemetery layout, and church records.

A famous study conducted by James Deetz in 1977 examined the different engravings on headstones in New England Puritan cemetery and discovered a gradual change in cultural identity and ideology. The markings shifted from the Death’s-head to cherub and finally a willow and urn design. Each one represents a softening of the rather harsh death’s-head engraving. Deetz also discovered that the inscriptions changed from a rather individualistic phrase to the now common “In Memory of…”. Other archaeologists examined similarly aged cemeteries in New York to see if the trend was more local or denominational rather than regional. They discovered that this trend of softening and commonality was true for other cemeteries. Deetz and the other archaeologists were able to track iconography and cultural changes without putting a single shovel into the ground.

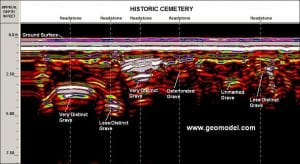

Just because something is buried in a graveyard does not mean it is outside the reach of archaeologists. Geophysical techniques such as ground-penetrating radar (GPR) make it possible to see changes under the ground without disturbing it or the spirits who rest there. GPR sends radar waves into the ground and measures the time it takes for the wave to bounce off an object and return to the sensor. Different objects, such as a coffin, and soil compositions, like a grave shaft, will bounce signals back at different times creating an anomaly in the GPR recording. While GPR and other geophysical methods cannot specifically tell an archaeologist what an anomaly is, they can provide information of what possibly lies below the ground. Graves then to be 2-meter-long rectangles that line up side by side with one another. If such an anomaly pops up during a graveyard survey, it is likely a grave, especially when it is associated with a visible tombstone. These types of surveys are great to locating possibly unmarked graves, determining the extent of an unmarked cemetery, and seeing if the current locations of tombstones line up with likely graves.

Using these non-invasive methods of cemetery analysis lessens controversial nature of the investigation. Descendants and caretakers might be more willing to allow research that will not disturb the souls at rest. These investigations also prevent the researchers from being haunted by the spirits that roam the grounds.

Follow IUP Anthropology at Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram