Written by Jesse Metzler

A fascinating aspect of the history of Indiana County is its link to the Underground Railroad. Individuals interested in history have likely noticed the PA Historical Markers scattered around Indiana County that describe the anti-slavery efforts of the population. One such marker is situated near the corner of Philadelphia Street and South Sixth Street and tells Anthony Hollingsworth’s story. Hollingsworth was one of the known freedom seekers who traveled through Indiana and was the victim of a kidnapping by bounty hunters. Hollingsworth ultimately received legal assistance from the abolitionists of Indiana and eventually settled in Canada.

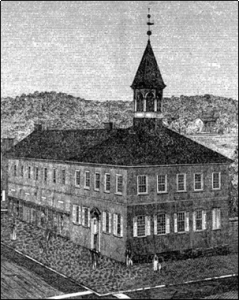

The Indiana Courthouse circa 1856, the site of the Hollingsworth’s kidnapping trial. Source- Blairsville Area Underground Railroad 2021

There are Underground Railroad sites dispersed across Indiana and Blairsville, including historic buildings and potential archaeological sites. However, there is no definitive inventory of Underground Railroad related properties in Indiana County. The impetus for this thesis was an interest in researching a viable method for recording and preserving a delicate portion of the historical record. This thesis examines the utility of the National Register Multi Property Documentation Form (MPDF) as a tool for preserving Underground Railroad resources in Indiana County by analyzing three case studies. These case studies are based on MPDFS submitted for Underground Railroad resources in three states: Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. Examining the MPDFs for these states indicates that cultural resource professionals can utilize them to identify and document Underground Railroad sites.

This thesis’s field component focuses on a historic property

An interpretative sign describing the life of John Graff. The marker is a part of the Blairsville Area Underground Railroad’s driving tour.

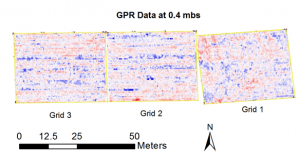

in Blairsville linked to the Underground Railroad. The John Graff House was constructed for John Graff during the early nineteenth century. Graff was a prominent entrepreneur, politician, and philanthropist who held abolitionist ideals. Graff was one of the reported abolitionists of Indiana County who reportedly assisted individuals that utilized the Underground Railroad. Local history suggests that Graff constructed a tunnel under his property that ran to the bank of the Conemaugh River, allowing for discrete travel in and out of Blairsville. The Graff Property was the subject of a Historic Resource Survey Form (HRSF), which included an architectural survey of the house. A ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey was conducted to ascertain the presence of a tunnel on the property. The HRSF was intended to serve two functions, including the documentation of a known Underground Railroad related property and a potential starting point for developing an MPDF for Underground Railroad resources in western Pennsylvania. MPDFs offer CRM practitioners the ability to develop a framework for identifying and documenting historic properties and archaeological sites. There is considerable potential for an MPDF to aid in preserving the Underground Railroad resources of Indiana County.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram