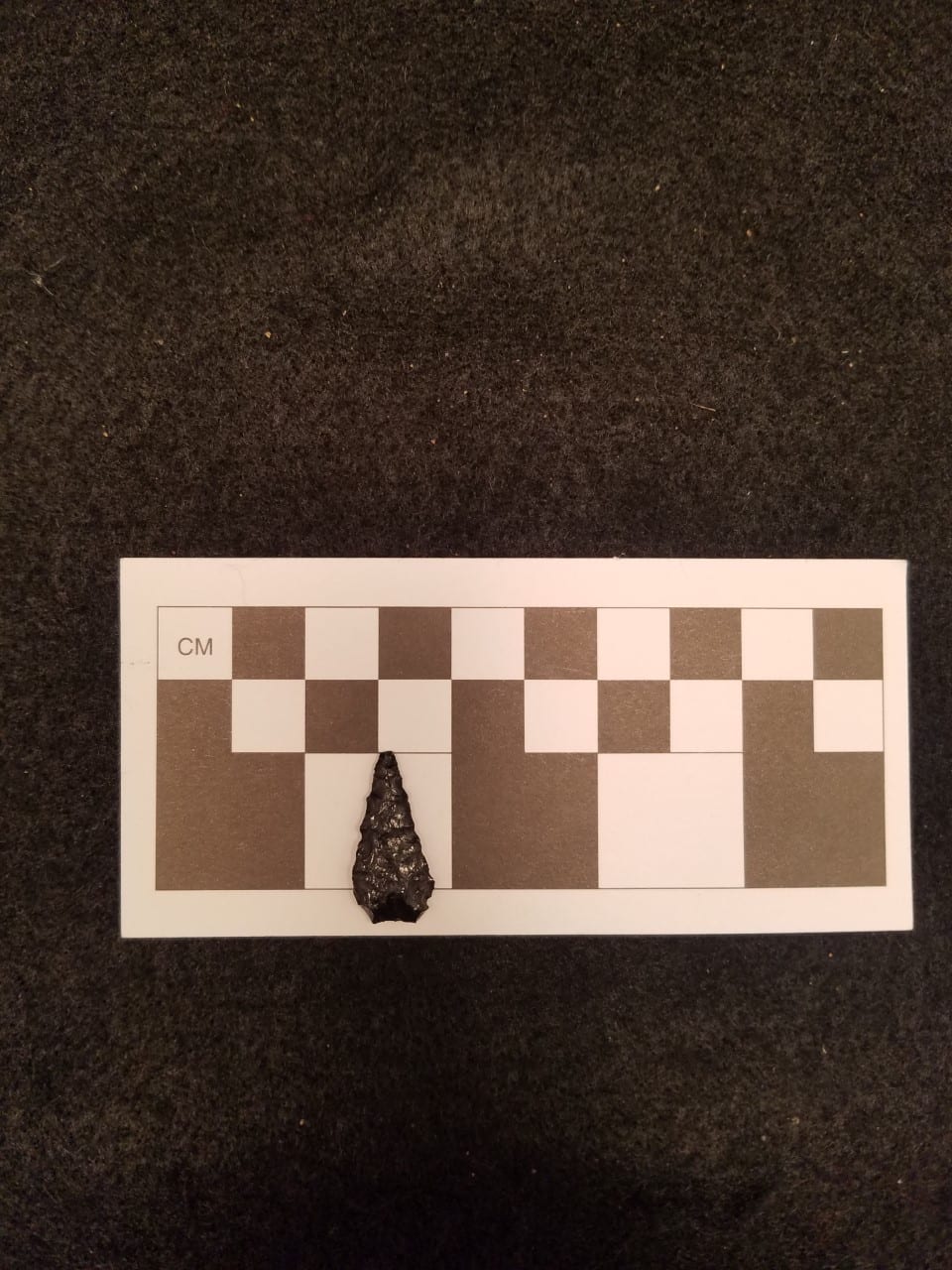

I’ve been snooping around the old, donated collections that we keep in the big lab room. Partly for my own curiosity and partly to find something Instagram (@iup_archaeology) worthy. Honestly, there are some amazing artifacts but there’s so little information about them. Given time and a few good resources, I could probably narrow down the projectile points to typical typologies found in Pennsylvania and the surrounding areas. I might even be able to narrow the types further if the associated note cards have any useful or reliable information, but half of them are blank beyond an artifact number. It’s unfortunate, I wish I could know more about the what, where, and when but that’s just how the cookie crumbles. I guess it goes without saying, but that’s the downside of collectors doing what they love to do.

An artifact without provenience provides far less information than one with provenience. Some archaeologists might even go as far to say that an artifact without provenience, or more specifically, an artifact from a private collection is useless since we can’t confirm anything about it. Those same archaeologists, well, let’s say they’re probably less than willing to take any information provided by a collector seriously. Their skepticism renders provided information, as limited as it’s likely to be, useless and I can’t say that doesn’t have some valid reasoning behind it. However, I would like to argue that an artifact without provenience or with questionable provenience remains useful for archaeologists. Not as useful as it would have been, but we can still potentially learn from it. For example, if we were to look at a private collection from the Squirrel Hill site. Sure, the current holder of the collection might not be able to tell us where every artifact came from exactly, but as Squirrel Hill has been plowed over the years, these items would not have been found in context beyond the tilled soil (if they were surface collected). It would have assured us that these artifacts came from the site but if a collector has documented the location, maybe through a photo or a GPS point, then that’s arguably reliable for connecting it to the site. Again, I’ll say arguably because there is room for skepticism. So, how would this be useful? Frankly, it would be an example of material culture from the site, adding to our understanding of what material culture from that site could be like. Again, leaving some room for skepticism but considering the possibilities. Something out of context could also prove useful for interpreting the humans behind the tool. You don’t need to connect it to a culture to ask why something was made or how it was produced. Sure, connecting to a culture helps answer these questions by bringing in specifics and potentially comparisons of similar samples.

I think I’m rambling, so I’ll try to sum up my point. Even if an artifact lacks context, it is still a piece of the archaeological record. I see the information it provides, as limited as it may be, as worth having and using even if it means including an asterisk to keep potential issues in mind. I’d rather we take the time to work with collectors, to gain whatever information that we can, than to lose out on everything.