December 28, 2018 (updated January 3, 2019)

This is the thirteenth in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

Warning: Spoilers! Spoilers! Spoilers!

Fans of speculative fiction—whether novels, movies, or videogames—anticipate with delight the sharp, alienating discovery that starts every story. How will this world differ from our own? How are its rules different than our own? Will it be a world where every moment of our lives are recorded and rewatched at will? Will it be a world where parents monitor and control their children’s every experience? Or one in which criminals can be sentenced to relive the terror they inflicted on their victims—and do so for the entertainment of others? Or maybe this is a story in which characters discover that they are not the agents of their own destinies, but are mere toys, played with by unreachable powers?

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, the movie-length release from director David Slade and writer Charlie Brooker, doesn’t just give viewers one of these estranging delights, but all of them (and more). In this respect, Bandersnatch continues the self-reflexive turn in Black Mirror that we saw in the concluding episode of its fourth season, “Black Museum”, which follows its main character on a tour of some of the gnarlier plot devices of earlier episodes.

But the best and most disarming shock of Bandersnatch happens before the story even starts. Not only is this a movie-length story, but it’s a fully interactive movie, a true cinematic choose-your-own-adventure book. The film occasionally pauses and asks the viewer (though I guess that makes us a player now) to make a choice for the protagonist. While riding the bus, does Stefan listen to The Thompson Twins or a Now That’s What I Call Music! mix tape? When Stefan (Fionn Whitehead) grows frustrated with the progress of his videogame project, does he throw his tea at the computer or shout at his father? It’s a surprisingly complex operation and fascinating to watch . . . I mean play. Did they really film two scenes so that I could choose Sugar Puffs or Frosted Flakes for breakfast? And did they do it again so that our choice appears on a television commercial at the end of the movie? Yes, my friends, they did. During my first playthrough . . . er, viewing . . . I counted about 40 choices, exclusive of a couple of recursive loops. There are several different endings and a kind of rudimentary scoring system, too (concerning how highly your game is rated by the twit on a weekly news segment). If you’re interested in seeing how it all plays out, you can check out this compendium of fan-created guides and plot diagrams.

This makes Black Mirror: Bandersnatch a double-good example of “videogame literature.” On one hand, it is a movie about videogames. Stefan is an up-and-coming videogame designer who has landed his first big chance at publishing his work. We watch him as he struggles to complete his game, as he crunches to get it done by deadline. We see characters play videogames and those games provide a sense of historical specificity to the episode, placing us squarely in the era of PC classics like Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord and Jumpman. We watch Stefan watch a television show about videogames (the one with aforementioned twit). On the other hand, Bandersnatch explores the meaning of videogames, both for those who play them and for the broader culture. Videogames function as metaphors in the episode—of Colin’s death, of Stefan’s trauma, and of our collective desire to be entertained by the suffering of others. (For a detailed explanation of what “videogame literature” is, see my post.)

But back to the experience of the pleasurable shocks of speculative fiction. The second one we get with Bandersnatch is a bit more mundane, simply a matter of establishing the setting for the story. For this episode of Black Mirror, we’re not in the future, but in the past, 1984. For aficionados of paranoid fiction, the reference to George Orwell is obvious. But this is not an Orwellian story. There is no authoritarian state looming over the struggles of young Stefan, no boot on the neck, no 2 + 2 = 5. And while we can take Stefan into a mind-bendingly paranoid storyline involving a secret research project, the authorities here are first and foremost the old-fashioned archetypes of mommy and daddy, mommy in this case played by Stefan’s therapist Dr. Haynes (Alice Lowe), daddy by Stefan’s daddy (Craig Parkinson). Cementing the Oedipal framework, Stefan harbors a deep emotional trauma involving the death of his mother, a death caused by his intemperate love of a toy rabbit taken by his father out of fear the boy would be insufficiently masculine.

(I am sorely tempted to analyze the penile pun of the software company that has purchased Colin’s game—Tuckersoft—but I will defer.)

If Orwell proves something of a phantom, other writers have a more durable presence in the episode. Lovers of Lewis Carroll will recognize the beastly creature in the title. The “frumious Bandersnatch” appears three times in Carroll’s writings, twice in Through the Looking Glass and once in his poem “The Hunting of the Snark.” And there is a decidedly “frumious” monster in Black Mirror: Bandersnatch and a magical mirror, too! The Carroll reference can be read in a couple of ways. Through the Looking Glass was a commentary on children’s literature. Similarly, Bandersnatch is a commentary on movies—specifically, on the medium of streaming cinema. Stefan eventually discovers that we are making decisions for him and, in response to his panicked query, we can, if we wish, tell him we’re watching him on Netflix. Paranoid humor ensues. The Carroll reference is ironic in a second way. In addition to being frumious, the Bandersnatch is notoriously difficult to catch, but, if caught, is vicious. We recall the Banker in Carroll’s poem who accidentally fell upon one and, despite his offers of a “large discount . . . a cheque (Drawn ‘to bearer’) for seven-pounds-ten,” found himself quickly turned to bloody ribbons. I’ll return to whether Stefan (or we) catch the beast and what damage, if caught, it causes.

(See it there on the left?)

The other writer with significant presence in the episode is Philip K. Dick. A reference to my favorite Dick novel, Ubik, appears in the scene in which Colin (Will Poulter) offers Stefan the choice of taking a dose of high-quality acid (or drops one, unrequested, into Stefan’s tea). Beyond the hippy-trippy, psychedelic-paranoia stuff, the spirit of Dick is most evident in the movie’s representation of Stefan’s struggle with mental illness and in its exploration of the evergreen conundrum of free will versus determinism.

Stefan struggles with mental illness and the therapy and medicines that are prescribed him. His therapist Dr. Haynes urges him to explore his trauma, to re-tell the story of the toy rabbit, the insensitive father, and his mother’s death. Stefan complains, “What good does it do, going over things again and again?” But Haynes perseveres: “Think carefully. You really might learn something new.”

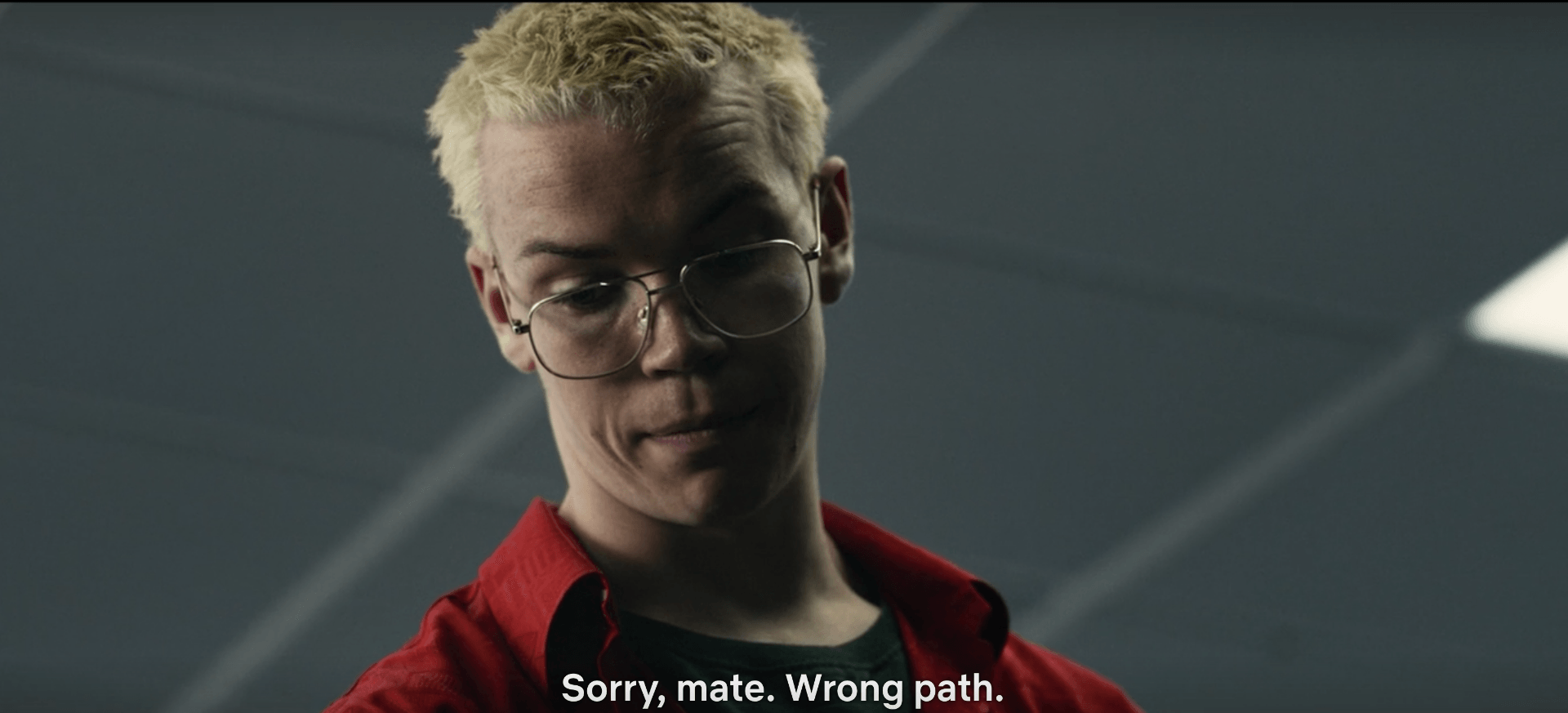

Stefan’s struggle with his mental health is complemented by the multiple metaphors of limited agency in the episode, several of them tied to videogames, videogame play, and the culture of videogames. One of the first decisions we make for Stefan is whether he will work on his game by himself or with members of the Tuckersoft team. If we choose the latter, the result is a bad game and a restart. “Sorry, mate,” Colin japes, “Wrong path.”

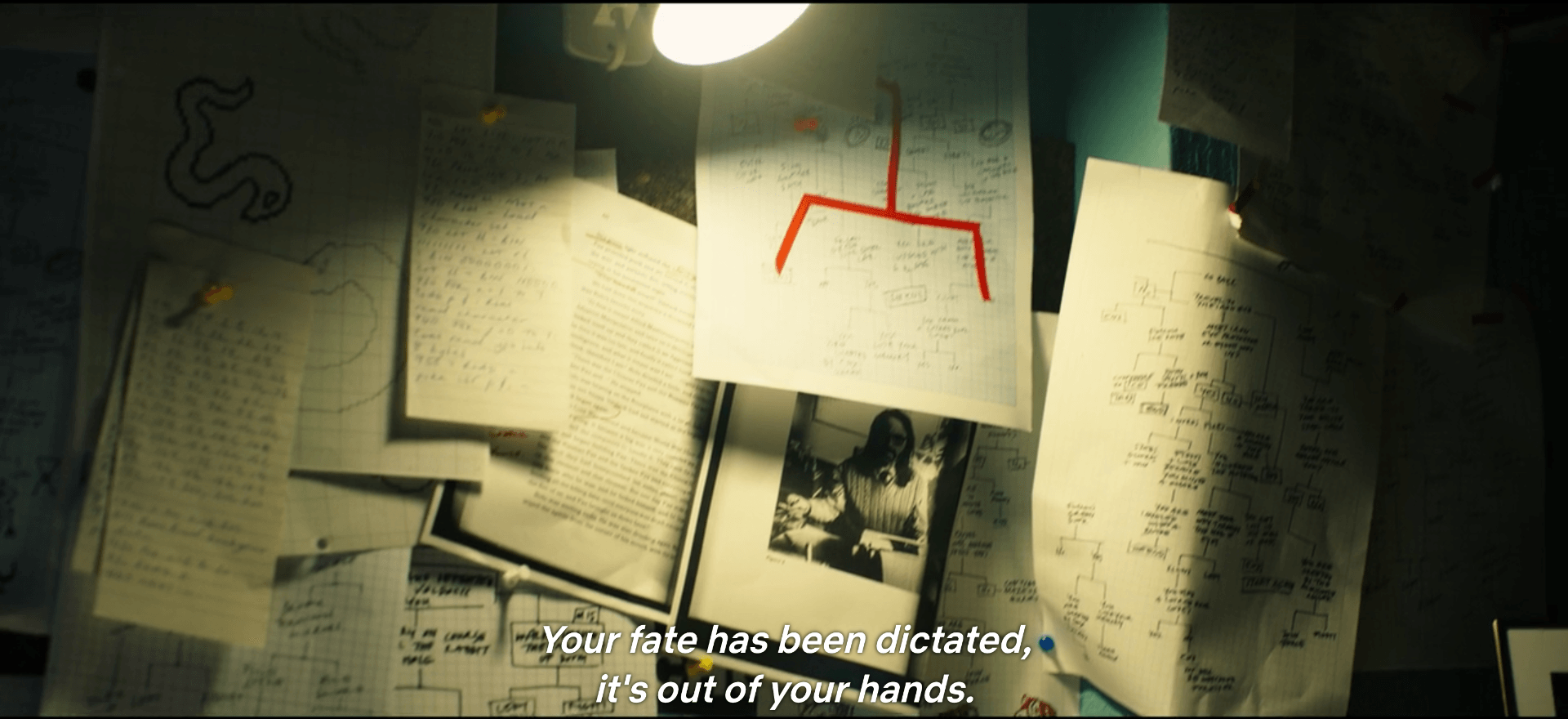

There is, of course, the genre of game Stefan is developing, a branching narrative. The figure of the branching narrative is the most important in the episode. Stefan has many choices to make, but most of them are binary. Does he say, “Yes” or “Fuck yeah!”? But the simplicity of the specific choices are counterbalanced by the struggle to make sense of the decision system as a whole. As anyone who’s designed a branching narrative knows, things can get out of control quickly. And that’s the case here. Stefan struggles not only to make his game work, but to get it done. There are too many branches to explore.

Another figure of limited agency is the maze. Stefan’s branching narrative looks like a maze when we see it diagramed. And it is nested within a 3-D maze game reminiscent of Wizardry. The legendary maze-runner Pac-Man makes a cameo. During their acid trip, Colin explains that the “PAC” in Pac-Man stands for “Program and Control.” “He thinks he’s got free will,” Colin rants, “but really he’s trapped in a maze, in a system. All he can do is consume. He’s pursued by demons that are probably just in his head.”

Towards the end of the game . . . er, movie . . . Stefan has increasing difficulty understanding what is real and what is fake. At one point, he finds himself on a movie set, the set of, you guessed, it, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. The decision we instructed him to take—to leap out the window—isn’t in the script. “You’re not scripted to jump out, see, Mike?” the director tells him. Philip Dick would find all of this perfectly amusing.

Regardless, all this drug-dosed epistemological tomfoolery is ultimately beside the point. Black Mirror has always been concerned not so much with how media shapes our relationship to power. Thirteen of the 19 episodes of Black Mirror are about entertainment media—videogames, television, social media, virtual companions, virtual reality, and so on. That’s the case with Bandersnatch. For all of its trippy pondering of epistemological uncertainty and the possibility that our lives are simply an extended experiment in trauma induction, Bandersnatch is, in the final analysis, a commentary on entertainment. When Stefan tries to explain to Dr. Haynes that he’s being controlled by a 21st-century entertainment technology called Netflix (presuming we chose that particular branch of the narrative), she asks, “So, why aren’t you in a more entertaining scenario?”

Maybe not for him, but definitely for us.

We’re entertained by Stefan’s struggle to manage his mental health. We’re entertained by the silly little choices we make for him. We’re entertained by the possibility that we can make Stefan do something stupid, or violent, or self-destructive. We’re entertained by the hand-to-hand combat between Stefan and his double-baton-wielding therapist, by the arch jokes about Netflix, by the unfolding narrative of paranoid control.

Let’s not forget a couple of key details. The book on which Stefan’s game is based was written by a man who, after repeatedly dosing himself with high-octane hallucinogens, brutally murdered his wife, using her blood to repeatedly paint an inverted, rectilinear Y on the walls of his home, an iconic representation of branching narrative and the false choices they present. Colin’s suicidal leap off his high-rise balcony juices sales for his new game Nozhdyve. Similarly, as he sits in prison, serving time for the murder of his father, Stefan watches a reviewer judge his game as “a morbid curiosity at best.” All three creators attempt to transform their trauma into art. All fail. But we get the fun of it.

But is it truly fun? Is this an entertaining scenario? One of the lures of literature built around branching narratives is the desire to fully explore all the possibilities. After completing my first playing (er, viewing) of Bandersnatch, my first thought was to rewatch (er, replay) it and make different choices, to explore all possible branches, to see whether I might get a different ending. But as I considered the possibility, the old adage about madness came to mind. Wouldn’t I just be doing the same thing over and over again and expecting something different to happen? And I started to think about my media-consumption habits more generally. Binging episodes. Grinding games.

Which led me, oddly enough, to a question: Why is Black Mirror: Bandersnatch set in 1984?

Again, it’s not about Orwell. And it’s not about the whole paranoid, Dad’s-a-secret-scientist-and-I’m-in-an-experiment-that’s-also-a-Netflix-movie that can be found in one of the narrative branches. That’s just smoke and mirrors.

When the movie (or is it a game?) ended, my first thought was that it was asking some difficult questions about whether we can know the system in which we exist, the social, economic, medical, and emotional systems that make us who we are, that shape the decisions we make, and give us the tools to understand ourselves and our world. It was about the stakes of knowing the system, of recognizing its evil. It was about the risks we run when trying to get outside the system.

But as I thought about it more, I realized that Stefan’s effort to know the system, to work out all the branches of the narrative he’s creating and the narrative he’s in, is fruitless. Stefan can’t work out all the bugs. In several of the episode’s endings, Stefan’s game is released in incomplete form, and he’s left rotting in jail, raving. I don’t have the time or the will to watch Bandersnatch a dozen times. That’s not a grind I want to grind. But regardless of whether he or we are able to figure out how the system works, all that bingeing and grinding is generating profit for Netflix and funneling more and more data into the privileged figure of agency and control of our moment: the algorithm.

Understanding the rules of the game isn’t the point. The big question is whether we play the game at all, because this game is part of a bigger game, the game of data collection and marketing.

Which leads to a final question relating to the most paranoid of the game’s branches. What happens to Stefan’s mother and his memories of her when it is revealed to him that his life was nothing more than an experiment? What happens to the guilt he feels about his mother’s death, the anger he feels towards his father’s refusal to abide by her desire to raise a sensitive child? What happens to Dr. Haynes, Stefan’s surrogate mother? Why does she suddenly change from a sensitive, empathetic, insightful therapist to a trained assassin and then an actor on a set? Bandersnatch’s treatment of women is troubling, in a good way. As the epistemological uncertainty increases, so does the unreliability of the women in Stefan’s life. Both his mother and Dr. Haynes change from emotionally potent figures to actors playing roles. The issues that Stefan needs to address–the gnarled knot of emotional trauma and neurochemical issues that his father and therapist have been urging him to take seriously, that Stefan has been taking seriously–are revealed as tricks to keep him locked into a sci-fi experiment.

The last time I saw Stefan, he was stuck in his cell, watching a televised review of his “morbid curiosity” of a game, while he repeatedly scratches the icon of the branching narrative onto the wall. He’s there not because of the decisions he or we have made (or didn’t make). Stefan is there because he failed to deal with the facts of his situation. He cannot escape his guilt for his mother’s death. Are there other endings for Stefan? Yes, but what does it matter? He cannot escape his mental illness. He cannot stop hating himself. He cannot stop hating his father. His desire for escape—for a solution to the puzzle, for the right sequences of moves to get out of the maze—is the source of his suffering. Stefan will never catch the Bandersnatch, but it’ll end up eating him anyway.

The simple fact of the matter is that this isn’t a very entertaining scenario, at all.