This is the second in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

(Spoilers)

What’s not to love?

In case you missed it, Ready Player One is Ernest Cline’s post-apocalyptic 1980s nerd-culture spank-bank novel, and you either really, really—I mean really—hate it or sort of, kind of love it, but maybe feel a bit yuck about the relationship.

If you haven’t heard about Cline’s novel, you probably also didn’t hear that it’s being made into a Steven Spielberg CGI-saturated blockbuster wannabe attempting the rare feat of putting millennials and Gen-Xers shoulder to shoulder in up-sold premium theater seats and social-media rages.

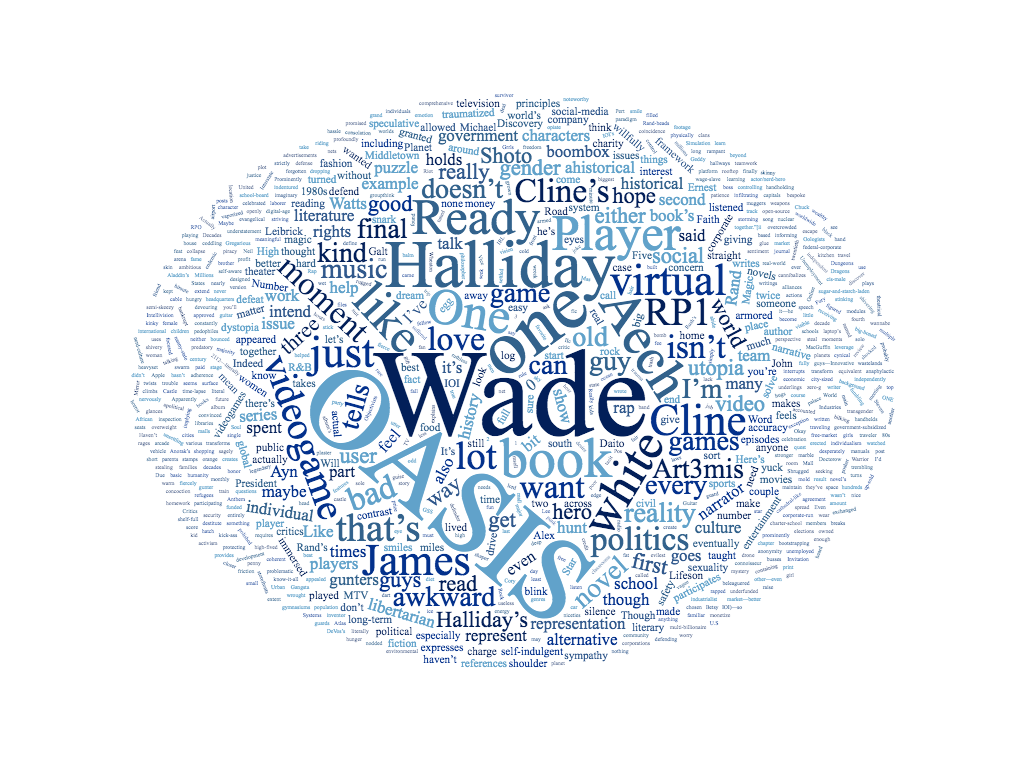

RP1 is a perfect example of what I call “videogame literature.” Cline deploys multiple tropes of videogame literature—the diegetic representation of games, players, and player culture; the figurative use of the same to represent abstract values and ideas; intertextual references to games (so many references to games, so fracking many, the horror . . .); the narrative adaptation of game procedures like leveling, respawning, and modding.

But the book also feels like it matters to our moment in some fashion. I’m not sure I’d call it a “zeitgeist novel.” It doesn’t feel like it has a whole lot to say about our moment, but along with Black Mirror, Westworld, and Jumanji, RP1 appears to signal the full emergence of video games and game players as subjects of serious consideration in popular entertainment.

So, full disclosure: I’m on the “kind of love, feel a bit yuck about it” team. I’ve read the book (signed by the author himself, appended with his usual “MTFBWYA!”) three, maybe four times, listened to it three more (Will Wheaton’s performance is quite good), including twice with my twin sons on the 10-hour trip between Pittsburgh and Leland, Michigan. I’ve taught the book a couple of times in graduate seminars. I get a bit laughy-cryey when Wade takes out the big bad guy during the big bad battle at the end.

There’s a lot in it for someone like me to love. I just turned 50, so that lands my awkward adolescence smack in the 1980s. And though I played a lot of sports and earned Eagle Scout, I was mostly an indoor kid. I watched enough basic cable to worry my parents (I don’t think I did a minute of homework that wasn’t in front of the television), read a fair amount of speculative fiction, owned a shelf-full of Dungeons & Dragons manuals and modules, and spent hundreds of hours playing video games (Apple IIc, Intellivision, a score of handhelds, the semi-skeezy arcade a couple miles away from my house, the posher Aladdin’s Castle at the mall). Like Wade Watts, the narrator of Ready Player One, I was an awkward, white, straight, cis-male who had trouble talking to girls. And get this! I lived just a few miles south of Middletown, the home of one of the novel’s main characters, James Halliday, and the location of one of its more unsettling episodes. For someone with my background, Ready Player One (RP1) is the literary equivalent of a bespoke suit.

Actually, there’s a lot not to love . . .

Not that I want to wear it. There is a lot not to love in Cline’s concoction. Critics (for example and example) have focused especially on its fumbling of female and transgender characters. Word. The joke about OASIS women actually being an overweight, hirsute guy named Chuck is awkward the first time Cline tells it, stinking up the kitchen by the fourth.

The IRL meeting between Wade and Aech is especially embarrassing. Haven’t read it? Here’s how it goes: Due to plot twists, Wade and Aech have to log out of the OASIS and travel together in an actual vehicle to an actual airport. But when Wade climbs into the armored RV that Aech uses as a home, he’s shocked to discover that his best friend, who he thought was a white guy, is in fact a “heavyset African American girl . . . with short, kinky hair and chocolate-colored skin” (318). Wade is gobsmacked.

Aech, on the other hand, is anaphylactic. Wade tells us she “appeared to be shivering, even though it was nice and warm . . .” (318). Aech eventually turns and smiles, but Wade holds his silence. Aech “kept stealing glances at me; then her eyes would dart away nervously. She was still trembling” (318). The ice eventually breaks and smiles and hugs are exchanged, but to review: Aech is an independently wealthy, international arena sports star, solo traveler of the Road Warrior wastelands of the U.S., and big-boned black woman with a gift for trash talk. But one look from a skinny white guy and she goes all shivery?

Please.

Then there’s the book’s manic intertextuality, which drives some readers into spasmodic fits of spit-flecked disgust. Alex Nichols, for one, rules the “reference-to-plot ratio” so out of bounds that “it often feels more like binge-reading 1980s-related Wikipedia articles than reading a novel.” But, honestly, that’s a matter of taste. It’s not like Cline’s the first one to go full-encyclopedia. In fact, he’s in pretty good company: Dante, Rabelais, Cervantes, Goethe, Melville, Joyce, and Pynchon all gave it a shot.[i] Wade’s no Ishmael, granted, but I kind of like his obsessive attention to detail.

But, again, I come here not to bury Ready Player One, but to praise it, sort of.

We need to talk about Wade

Ultimately, I want to make the case that Cline’s book is a lot smarter and more self-conscious than its critics have allowed. Indeed, many of its most nettlesome aspects (including its treatment of race, gender, and sexuality) look very different when we fault not the book’s author, but its narrator: Wade Watts.

Having read, taught, and thought about this book for a while, I’ve come to think of Wade less as a digital-born Luke Skywalker than a traumatized refugee from a Philip Dick novel: Ubik, maybe, or Martian Time-Slip. To be blunt about it, Wade isn’t all there, and I’m not at all surprised.

Which doesn’t mean I’m letting Cline or his narrator off the hook. So, while I intend to defend RP1, I’ll defer that task to Part 2. There are a few other problems I need to address before I move into the positives.

Is the tuner on your boombox broken?

RP1 was published before Gamergate, granted, but the book is almost willfully ignorant of the history and politics of gender and sexuality in online spaces.

In an incisive reading of the gender, racial, and sexual politics of the book, Suzanne Leibrick criticizes Cline for failing to represent the OASIS as either a Star Trek-style utopia for women, the queer, and people of color (and therefore an alert cautioning us about the failures of our present moment and their long-term impact) or a fully-fleshed dystopia whose historical and social causes can be identified by an attentive reader. But the OASIS is ultimately an ahistorical representation of global virtual reality. “I really wanted Ready Player One to be more aware of this history,” Leibrick writes, “by either showing us just how bad things could be for anyone that’s not white and male, or giving us hope that things won’t always be as bad as they are today. Instead what we get is a book that mentions gender a lot, but doesn’t really understand what it is saying about it.”

Yep.

The ahistorical, incoherent representation of virtual culture extends to the way the OASIS sounds. A quick scan of the songs referenced in RP1 will surprise anyone who has spent even an hour in traffic with a dead phone and an 80s nostalgia station on the radio.

Where is Michael Jackson? Madonna? George Michael? Whitney Houston?

Where are R.E.M., Midnight Star, Erik B and Rakim, the Ramones, Sonic Youth, Run-D.M.C., Gang Starr, the Clash, Public Enemy, The Pixies?

Where. In. The. Fuck. Is. Prince?

The absence of alternative, punk, R&B, and rap in Ready Player One is just . . . well, weird.

For one, it’s completely, willfully ahistorical. Remember, I was a teenager who lived just a few minutes’ car drive south of Middletown. So, I know what the place sounded like. James Halliday could have tuned that boombox on top of his dresser to 97X out of Oxford, one of the first alternative rock stations in the country. Planet X, the station’s weeknight show, played alternative music from around the world and across the “fuck classic rock” spectrum. That boombox was also in easy range of 103.7 out of Cincinnati, the go-to when you needed to add just the right R&B and rap tracks to your mixtape. And if Halliday spent so much time watching MTV, how did he manage to miss Yo! MTV Raps?

The issue here isn’t just historical accuracy. However, in the spirit of historical accuracy (and self-indulgent snark), let’s reimagine the scene where our heroic gunters solve the puzzle of the third and final gate. Here’s what Cline writes:

Art3mis’s eyes narrowed. “Faith, hope, charity,” she said. She repeated them a few times, recognition growing in her face. Then she sang: “Faith and hope and charity . . .”

Aech picked up the next line: “The heart and the brain and the body . . .”

“Give you three . . . as a magic number!” Shoto finished triumphantly.

“Schoolhouse Rock!” they all shouted in unison.

“See?” I said. “I knew you guys would get it. You’re a smart bunch.”

“’Three Is a Magic Number,’ music and lyrics by Bob Dorough,” Art3mis recited, as if pulling the information from a mental encyclopedia. “Written in 1973.” (307-8)

Suggested edit:

Suddenly, an old white guy in a vintage 2016 Chelsea jersey appeared out of nowhere and smiled in a way that only know-it-alls who have their chance to show they know it all can smile. “But odd as it may be,” he rapped, as only old white guys can rap, “without my one and two where would there be, my three, Mas, Pos, and Me, and that’s the magic number.”

Aech and Shoto high-fived. “’The Magic Number!’”

Art3mis bounced her head to an imaginary beat, “De La Soul, 1989!”

“Word,” the old white know-it-all nodded sagely.

An awkward silence settled over the room.

Really awkward.

“Okay, I’m out, kids. Have fun storming the castle!.”

But the issue here isn’t about history (or self-indulgent snark). The issue is politics. The music Halliday listened to, the music Wade and his fellow gunters listen to, is noteworthy for its utter lack of concern for any real-world issues. My fan fic version of Art3mis is a connoisseur of Riot Grrls and Gangsta Rap.

But there is one major exception to that rule about politics and music: Rush’s album 2112 features prominently in the final stage of Halliday’s quest. “Prominently” is an understatement. Cline cannibalizes the album’s long track “Discovery” as the narrative framework for the final chapter of the book’s second part, the moment Wade takes his last virtual actions in the OASIS before physically infiltrating IOI corporate headquarters in the guise of an indentured laborer. It’s the moment he transforms from a literal guitar hero into a corporate drone.

If you’re not familiar with 2112 or “Discovery,” it is based on the book Anthem, by libertarian hero Ayn Rand. No, Geddy Lee, Neil Pert, and Alex Lifeson were not Rand-heads or evangelical Objectivists. But Rand’s writings were meaningful to the band. Lifeson explains: “What appealed to us was what she wrote about the individual and the freedom to work the way you want to work, not the cold, libertarian perspective. For us, it was striving to be a stronger individual more than anything, and that’s how the story came together.”[ii]

Ayn Rand: Guitar hero, video game edge lord

James Halliday would second that emotion. Like Rand, he has no patience with sentiment, no interest in the civil state or the safety net, no desire to define himself as part of a community. Though he helped create a virtual reality platform in which the majority of the world’s population participates, and though the final puzzle requires a team to solve, his favorite game genres are either single player or fall into the “chosen one” paradigm. It is no coincidence that, at the moment when Wade is most immersed in the world of 2112—literally immersed in it, as Halliday actually designed a planet around it—he must long-term log out of the OASIS and become a wage-slave to one of the world’s biggest and evilest corporations.

Why ask useless questions? How deep is the ocean? How high is the sky? Who is James Halliday?

The OASIS isn’t called the OASIS for nothing. It is balm and opiate. The world of Ready Player One has suffered a comprehensive energy, environmental, economic, and civil collapse. World capitals have been vaporized by nuclear weapons. Millions of refugees desperately seeking security. Unemployment and hunger are endemic. But none of that has found its way into the OASIS.

Apparently, the OASIS holds elections, implying there is some kind of OASIS government. We learn that speculative fiction writer Cory Doctorow is President, actor/nerd-hero Will Wheaton is Vice President, and Wade tells us they’ve been “doing a kick-ass job of protecting user rights for over a decade” (201). But that’s about the extent of it. So, not only are two old white guys in charge of a virtual world in which “most of humanity” participates every day, but the issues that matter don’t extend beyond “user rights.”

There seems to be a tacit agreement that no one participating in the hunt for Halliday’s egg is allowed to talk politics. Maybe that was in the small print of “Anorak’s Invitation”? Even Art3mis, the one character who expresses vague concern for social justice, hasn’t figured out how to leverage her worldwide social-media fame into any kind of virtual political activism. (This is not the case with the film. If the trailers are any indication, Art3mis is leading a revolutionary underground.)

If the OASIS is “an escape hatch into a better reality” (18), that reality is better because it’s a reality without politics.

Or is it? On closer inspection, the OASIS isn’t an apolitical space at all, but a libertarian wet dream. Decades of nanny-state coddling and federal-corporate handholding have turned the United States into Fury Road with food stamps. The cities swarm with the unemployed, grown fat on a “bankrupt diet of government-subsidized sugar-and-starch-laden food” (30) and bilking the government out of the money it provides poor families to raise their children. Interstate busses have to be armored, armed guards riding rooftop. Wade has to constantly guard himself against muggers and predatory pedophiles.

And let’s not even start with the schools: “The real public school system, the one run by the government, had been an underfunded, overcrowded train wreck for decades,” Wade tells us (31). In contrast, the OASIS public school system, funded entirely by Halliday’s company, Gregarious Simulation Systems (GSS), is a charter-school utopia, something out of Betsy DeVos’s dream journal: “every school . . . a grand palace of learning, with polished marble hallways, cathedral-like classrooms, zero-g gymnasiums, and virtual libraries containing every (school-board approved) book ever written.”

At the start of RP1, the OASIS is a free-market utopia, a place where “city-sized shopping malls” can be “erected in the blink of an eye, and storefronts spread across planets like time-lapse footage of mold devouring an orange. Urban development had never been so easy” (59). But the best part is, as Daito tells Shoto, “There are no laws in the OASIS, little brother” (153). And if a user doesn’t want to deal with the hassle of traveling to Planet Mall, they can simply steal what they want. IP piracy is rampant in the OASIS and openly celebrated by Wade. He doesn’t blink twice before informing us that his laptop’s “hard drive was filled with old books, movies, TV show episodes, song files, and nearly every videogame made in the twentieth century,” none of which he has paid a penny for (14).

And that’s what makes the bad guys—Innovative Online Industries (IOI)—so very, very bad. They want to monetize the OASIS, transform “the open-source virtual utopia” into a “corporate-run dystopia” (33). They intend to charge a monthly fee and “plaster advertisements on every visible surface” (33). They intend to end “user anonymity” and “free speech” (33). Halliday’s egg is just a MacGuffin. The real prize of the hunt is control of the market—better said, not controlling the market.

And what makes the good guys so very, very good is their adherence to the principles of rugged individualism. Though Art3mis expresses sympathy for the destitute and hungry, she, Wade, Aech, Shoto, and Daito are cynical, ambitious, and fiercely independent. In contrast to IOI’s “Oologists” and the members of the various gunter “clans,” the High Five abide strictly by principles of hard work and bootstrapping. They neither take nor give help to other gunters, or each other—even when teamwork would help them defeat IOI. Indeed, the moments of friction between the characters are the result of giving or receiving help from each other. And when they do finally team up to defeat the final boss, Cline interrupts their celebration by literally dropping a bomb on the party, with Wade the sole survivor.

But, of course, the OASIS and the hunt were not built by the High Five. That honor goes to James Halliday, a digital-age John Galt. Like Ayn Rand’s legendary hero, Halliday is a philosopher, an inventor, and a shaper of worlds. He is a fierce defender of individual rights, a ruthless critic of groupthink, an industrialist with no sympathy for social niceties or the needs of his underlings, a multi-billionaire with no interest in social safety nets or global political alliances. And the puzzle he creates for the beleaguered millions who seek consolation, entertainment, and profit from the OASIS isn’t really about money, but about James Halliday himself.

If the mystery of Atlas Shrugged is, “Who is John Galt?” in Ready Player One it is, “Who is James Halliday?”

So, about that defense?

I haven’t forgotten that I promised to defend Ready Player One, but I wanted to make sure we had fully accounted for what I was defending it against. I still maintain that what Cline wrought is much more self-aware than his critics give him credit. And if you’re not convinced that’s true, I hope you’ll at least stick with me that Cline’s vision of a video game future is as coherent as it is problematic.

The glue that holds it all together is trauma. Wade Watts and James Halliday are profoundly traumatized, both as individuals, and as straight white men.

And that is what I will discuss in Part 2.

Notes

[i] Megan Amber Condis alerted me to Ready Player One’s encyclopedic ambitions in her very smart essay, “Playing the Game of Literature: Ready Player One, the Ludic Novel, and the Geeky ‘Canon’ of White Masculinity.” It appeared in the Journal of Modern Literature 39.2 (Winter 2016): 1-19.

[ii] https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/rushs-alex-lifeson-on-40-years-of-2112-it-was-our-protest-album-20160329