July 25, 2018

This is the tenth in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

Note: “The Bittersweet Pleasures of Patriarchy Lite” was originally published by Kill Screen, the print and online magazine founded by Jamin Warren and Chris Dahlen. Shortly after the essay’s publication in the Fall of 2015, Kill Screen ceased publication. Concerned about the precarity of the site and my work, I’ve chosen to republish it here, though I’ve taken the liberty of making several changes that reflect some of the ways my thinking about irony, masculinity, and male-centered media has evolved and, more importantly, my sense that the moment of “Patriarchy Lite” is decidedly in the past tense.

(Spoilers)

Historically, patriarchs haven’t been fond of irony. Snark doesn’t mix well with either sanctimony or self-righteous terror. Irony is the bitter delicacy of disempowerment. The ironist works quietly, on the margins, drawing sly attention to hypocrisy, absurdity, venality.

The ironist enters a toilet in an art show (that was Marcel Duchamp’s move with Fountain). The ironist places a photo of Judy Garland on a makeshift bedroom altar; in the candlelight, they find sacred beauty in Judy’s eyes, in her addiction to pills and booze, in her mordant romances (that’s the classic move of gay camp). The ironist imitates the imitation to make us laugh at the artifice of the natural (that’s Dave Chappelle’s blind, black white supremacist Clayton Bigsby).

The ironist typically doesn’t do derring-do, doesn’t go for the gun. The whispered aside, the arched eyebrow, the double entendre—that’s more the style.

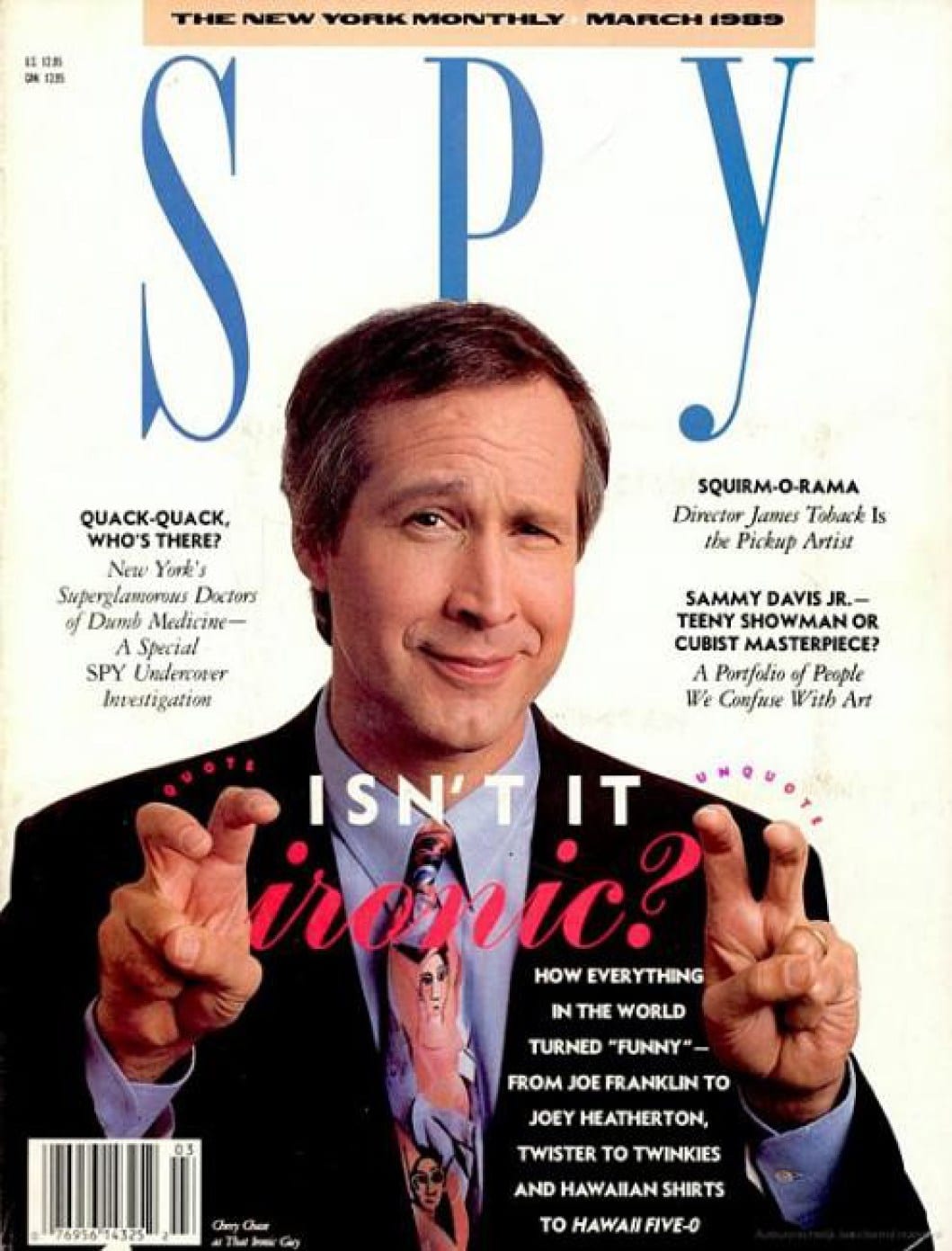

But the powerful and privileged eventually acquired a taste for the stuff. In a 1989 Spy magazine cover story, Kurt Andersen and Paul Rudnick call out a veritable “irony epidemic” rolling across Reagan’s America. The wealthy and upwardly mobile—we once called them Yuppies—stole the sly humor of avant-garde art, gay camp, and ethnic humor and ruthlessly pasteurized it into “Camp Lite.” The cultural dreck of the 1950s and 60s was transmogrified into “something to be pined for, something cute and pastel-colored and fun rather than racist and oppressive and un-air-conditioned.” Think vintage Hawaiian shirts, Leave it to Beaver lunchboxes, calling the wife the “old lady” as she rolls her eyes and cuffs the “old man” on the shoulder, neighborhood viewings of Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens.

The epitome of Camp Lite was air quotes: “the quintessential contemporary gesture that says, We’re not serious.”

But the irony epidemic didn’t just infect the upwardly mobile. Its hardiest mutation survived among a rising, albeit self-consciously “alternative” class of powerful and privileged. For a certain sort of alienated youth in the 1980s, less willing or able to ignore the demolition of the U.S. middle class, AIDS, Iran-Contra, hair metal, and the other brutal bullshit of the Reagan era, irony was a bulwark. Think Heathers, Bill Griffin’s Zippy the Pinhead, Devo. As a straight, middle-middle-class white boy living in a basic-cable cul-de-sac of Cincinnati, irony wasn’t an escape from politics or history, but a tool for finding them. For my friends and me, the air quotes signaled, We may be paying for this, but we’re not buying it.

Irony of ironies, when the millennium turned, we were the ones selling it.

Who is “we,” you might ask? Well, if you’d asked this in 2015, I’d say it was culturally informed, theoretically savvy, cis-white-male culture creators. In other words, folks more or less like me. But now, in 2018? In light of the Trump administration’s jaw-dropping attack on political and representational norms, in light of Breitbart, Fox News, and social-media bots, the market leaders in irony are no longer the makers of late-night television and cool videogames. They still look a lot like me, these “Fake News” followers, but their goals are decidedly un-ironic. But back to our story . . .

The Typhoid Mary of the epidemic was David Letterman. Like so many other Generation X-ers, I savored every dish he and his crew cooked up: the stupid pet tricks, Chris Elliott bits, 10-story bowling ball drops, all of that perfectly seasoned air-quoted awkwardness. Even as Letterman’s market grew among those dastardly Yuppies, I knew in my heart that he was still winking at me. I got the joke behind the joke. Of course, like so many other things I enjoyed in my youth, Letterman isn’t so fun now. Have you seen the gruesome little supercut of Letterman hitting on his female guests? Or his on-air response to the guy who attempted to blackmail him for harassing his female staff? Letterman ironized the genre (late-night talk show), the medium (television), and the culture (celebrity-gilded consumerism), but the air quotes never quite made it around patriarchy.

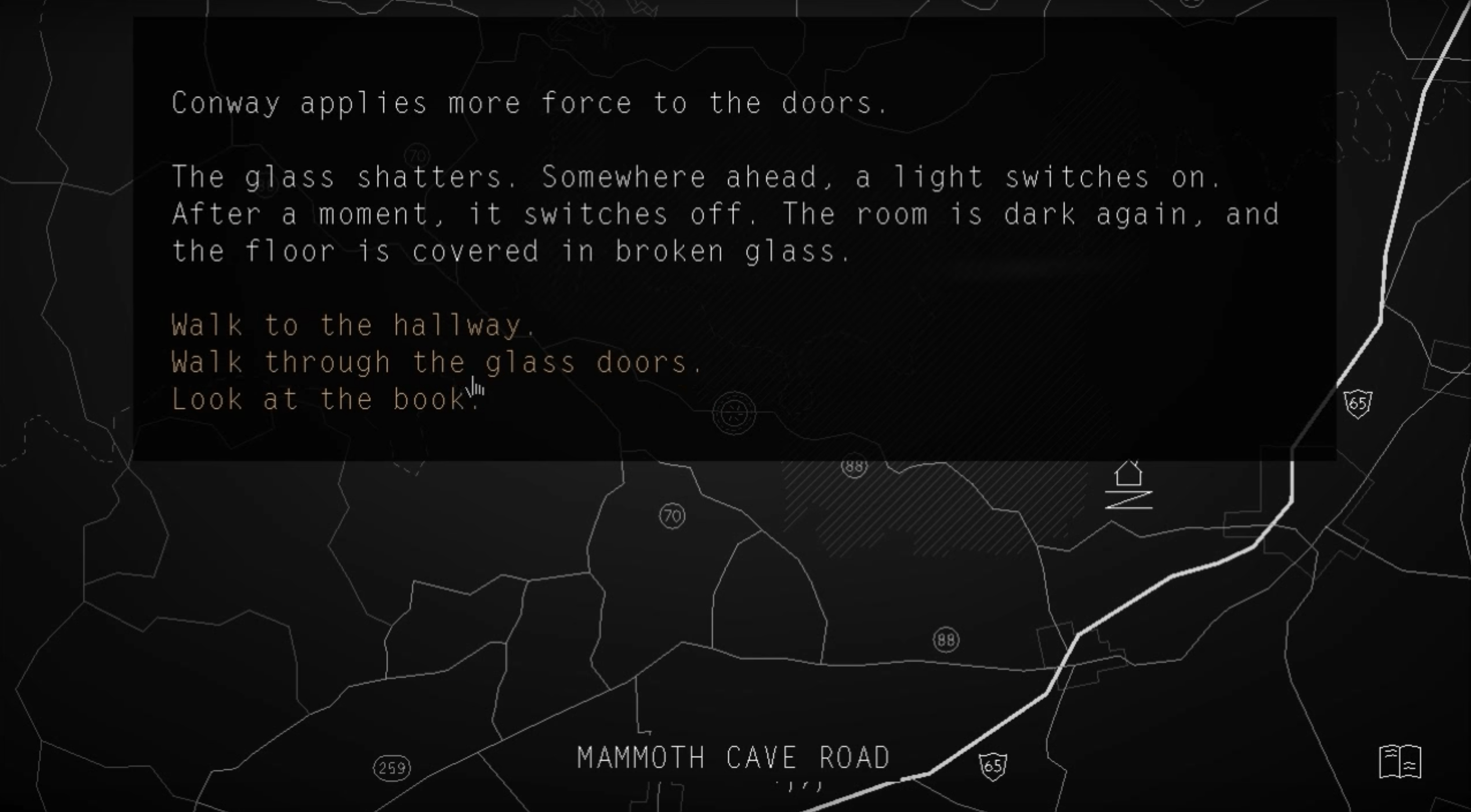

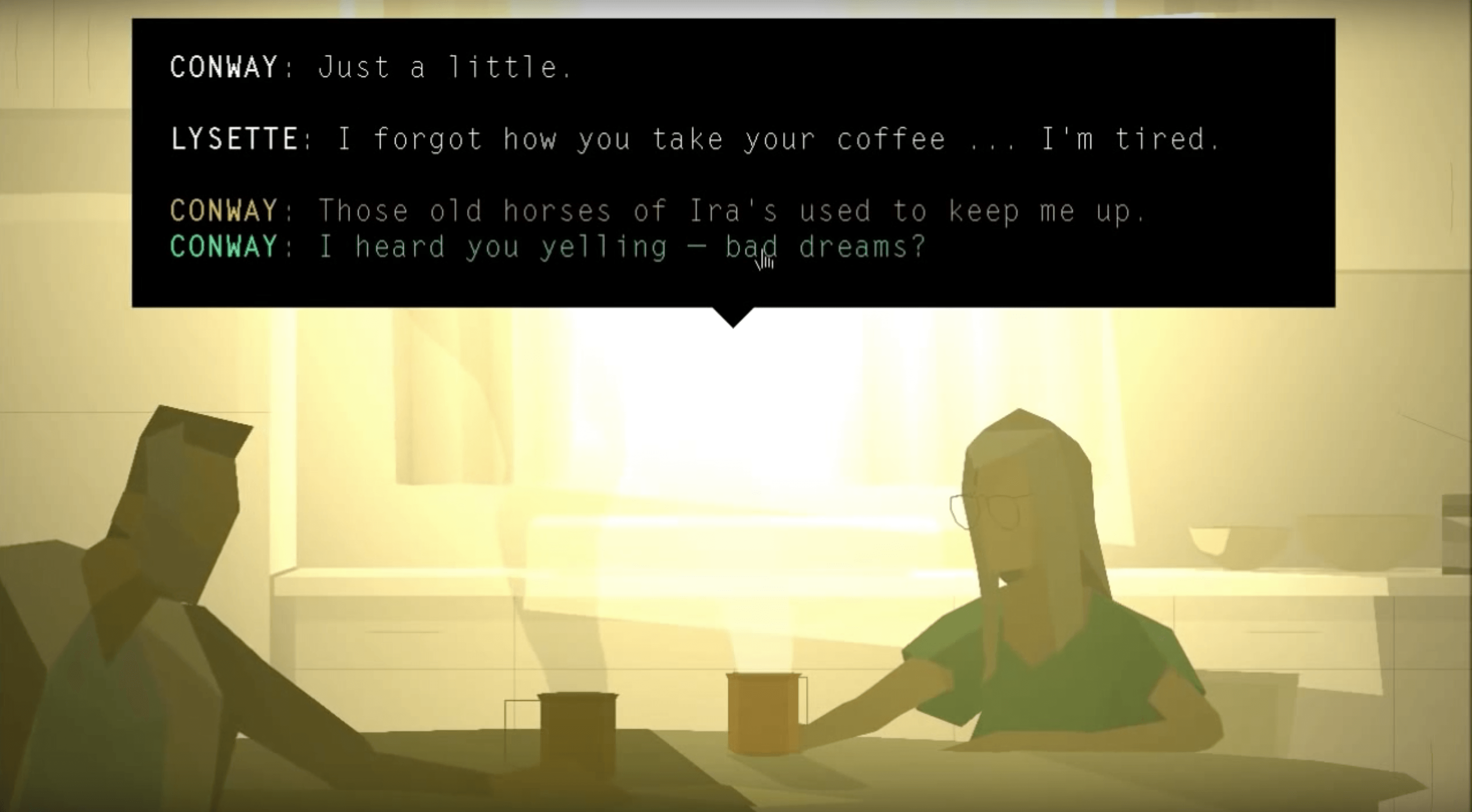

The same for videoames. The year Spy proclaimed the irony epidemic, a mass gaming culture had emerged from the debris of the 1983 crash. But Sega, Nintendo, Atari, NEC, Brøderbund, and other hard- and software companies were hedging their bets, designing and marketing the most un-ironic vision of power one could imagine. This was the grand era of the “Damsel in Distress” and “Woman in the Refrigerator” tropes. As Anita Sarkeesian shows, game designers compulsively deployed the same narrative hooks over and over again. Female characters were bundled away in ropes and chains, tossed in locked rooms, gut-punched, mutilated, and murdered to spur the white, heterosexual, cis-male hero to leap into action. I’d like to imagine that I played those games with some sort of critical distance, but honestly it’s not easy to make air quotes when your fingers are curled around a controller.

But I tried. Even when I was conscious of how backwards those games were, I knew there was something important about them, something that transcended the goon mentality of the market. I could figure out the trick with the air quotes, maybe.

Times have changed, as have consciousness, culture, the law, and the market. Sexual harassment is a meaningful legal category now and sexual predators are being called out, though victims still struggle to be taken seriously and the more powerful victimizers are still able to maintain their immunity. I teach videogame studies at my university and do so with the tools of feminism, critical race studies, and postmodernism.

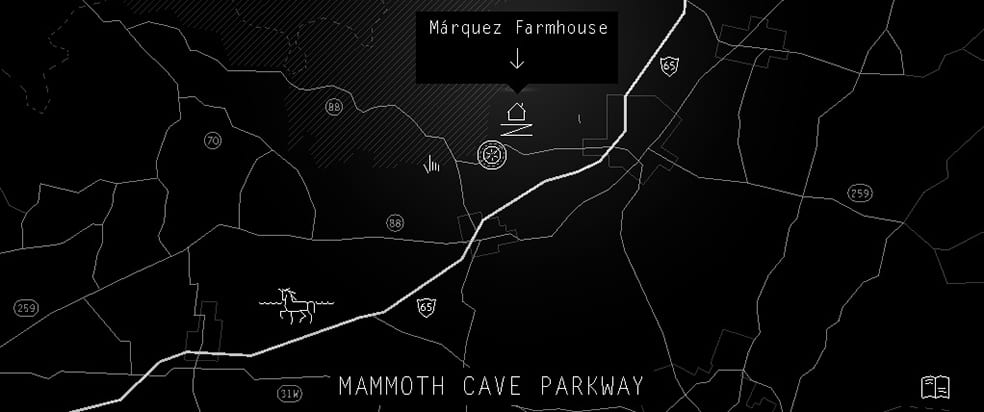

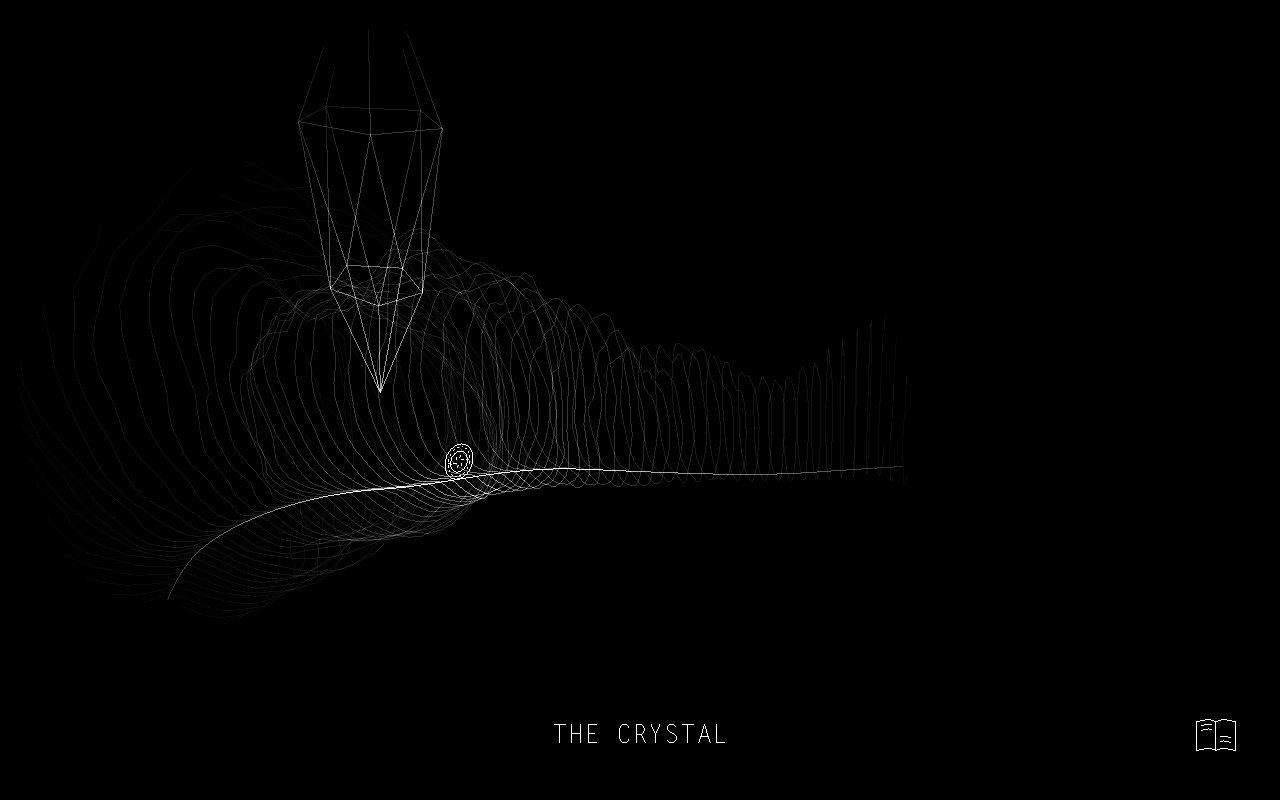

A new attitude towards masculinity emerged in U.S. culture during the first decade and a half of the 21st century, a new style of being manly, a new way of telling the stories of men, a new way of playing power. Masculinity became ironic. Let’s call this antigenic drift in the irony virus “post-masculinity,” or, with a fist bump to Andersen and Rudnick, “Patriarchy Lite.” Think moustaches, The Colbert Report, Mad Men, Louis CK, Obama in mom jeans, Judd Apatow’s bromances. Think Donald Trump’s hectoring, spray-tanned fist-pumping. Think BioShock Infinite and Braid.

The masters of Patriarchy Lite were the children of the irony epidemic, the first scions of Generation X. Stephen Colbert was born in 1964, Matthew Weiner (creator of Mad Men) in ‘65, Louis CK and Judd Apatow in ’67. The lead designer for BioShock Infinite, Ken Levine, was born in ‘66, Braid’s Jonathan Blow in ’71. (Unfortunately, I don’t know who designed Obama’s jeans.) This was a generation of men—and they were, almost exclusively, men, though Amy Schumer, Tina Fey, and Michelle Wolf played the game brilliantly—raised on stupid pet tricks, SCTV, Super Mario, and white hetero male privilege. They were expertly educated, too. Except for Louis CK, the son of Harvard grads, each attended an elite U.S. university. The masters of Patriarchy Lite could talk the beat-structure of a good masturbation joke and the choreographic nuances of a silly walk, but could also throw down feminism, critical race studies, and postmodernism, too. Oh, and sexually harass the women who work with them (looking at you, Louis.)

Not surprisingly, the dominant tone of Patriarchy Lite was ambivalence—that most ironic of emotions. And not surprisingly, the focus and source of those mixed and shifting feelings was manhood. Viewers of The Colbert Report were invited to simultaneously adore and be abashed by the chauvinist ravings of Colbert’s faux right-wing persona. They were expected to watch Don Draper drink, smoke, and fuck with an alloyed attitude of superiority, astonishment, and envy. They were meant to adore Apatow’s child-men because their masculinity was so vulnerable, self-conscious, talkative, pitiful. Never mind that they were also bountifully accoutered with the old-fashioned privileges of the patriarch: vintage collectibles, real estate, social networks, beautiful women.

The aesthetic correlative of ambivalence was juxtaposition, contrast, the mash-up. Louie plays like a conventional sitcom one moment, an indie film the next. In BioShock Infinite, we pause before a beautifully rendered statue of Rosalind Lutece and listen to a voxophone recording of a girl describing her admiration for a female scientist. A bit of plucky feminism and nuanced world construction to whet the appetite for the next high-caliber murder spree. Braid juxtaposes the exhilaration that comes from finally—finally—executing a sequence of leaps and bounces with moments of meditation on the small, poignant tragedies of youthful love.

The mash-up aesthetic of Patriarchy Lite reflected a pragmatic attitude towards the contradictions of our moment, a feeling that, as both creators and consumers, we had to make do with what’s available because there wasn’t an alternative—or perhaps the alternative wasn’t as fun. The intellectual ambitions of BioShock Infinite were both enabled and circumscribed by the market for first-person shooters. They were designed to promote forms of “critical play.” Mary Flanagan coined that term “critical play” to describe games that subvert player expectations, but the term also applies to the strategies that players use to stress and strain the mechanics and tropes of a game. And it applies to the mixed emotions that come from playing an ideologically repulsive game and deriving both pleasure and critical insight from it.

Hating your cake and eating it, too.

Readers, spectators, and videogame players who aren’t straight, white, cis males learned long ago how to get into a text at the same time as they kept their distance from it. In the first couple of decades of the 2000s, it seemed the straight white guys were learning to do it, too. That’s not a bad thing, mind you. Playing videogames with women and queer people was one of the ways I learned how to critically play. But that kind of critical sensibility can also add spice without changing the dish. The Apatowean bromance, for example, spoke at once to a desire to explore more deeply the feelings of love and friendship men can have for each other—but it also showed a stubborn unwillingness to think beyond the clunky conventions of 1980s rom-coms.

So, this wasn’t just pragmatism, a sense of making-do with the best one could get. Like the larger geek culture of which it is a part, Patriarchy Lite was stuck on the trashy treasures of childhood. Only a child of the irony epidemic would dream of designing a first-person shooter that takes on white supremacy, American exceptionalism, post-traumatic stress disorder, and quantum mechanics. An abiding fascination with childhood pleasures is characteristic of Braid, too. Tom Bissell captures it in the Atlantic profile of Blow: “Braid is a game about jumping on shit—and that Jon was audacious enough to take the platformer and make that into a grand statement about human existence is incredible.” Incredible, indeed. The discerning player relishes the game’s clever twists on familiar mechanics, its bountiful easter eggs and witty intertextual references. I felt a glow of geek tribalism when I saw that World 4-1 was titled “Jumpman” and laughed out loud when I saw the Donkey Kong echoed in its first screen (here’s a link to a playthrough). And I felt Blow’s frustration with players who don’t get it, who don’t see the big philosophical issues in play when we do something as simple as jump on a goombah, who don’t see themselves in that dapper little jumpman, who don’t give a shit that they don’t.

But this kind of sanctimony was just one more symptom of air-quoted masculinity: the obsession with boyhood hobbies was secured by the childish insistence that everyone else take those obsessions very, very seriously. Were he not so humorless, Blow would fit right in with Apatow’s tinkering, bong-hitting man-boys. Jason Segel’s character in Forgetting Sarah Marshall could just as well have been designing Braid as composing his puppet-opera Dracula. The triumphant premier of A Taste for Love could have been Levine’s 2008 PAX keynote. They’re the kinder, gentler, woke cousins to the Star Wars: The Last Jedi fan boys who drove Kelly Marie Tran off social media and who, with the utmost earnestness, started raising funds to remake the film themselves.

No less than Camp Lite, Patriarchy Lite was a creature of cultural and historical contradiction. It existed because critical consciousness about gender, sexuality, and race gravely outpaced political and social change, but couldn’t avoid hearing the criticisms of women, people of color, the LGBTQIA+ community. Indeed, it sometimes seemed critical consciousness was about to lap the culture it criticized. Patriarchy Lite existed because, with the exception of 4chan trolls, cloistered right-wing suburbanites, fanboys, and the majorities of most school boards, statehouses, and city councils in the U.S., everyone knew it was wrong that women, people of color, and the queer don’t make as much money as straight white men, are under-represented pretty much everywhere, aren’t fairly or accurately portrayed in textbooks, and are routinely beaten, abused, raped, and sexually harassed. Patriarchy Lite existed because what we knew about power was far ahead of the material facts of power.

Camp Lite was an expression of unmitigated privilege, of voraciousness without regard to cultural provenance, historical context, craft, or good taste. Camp Lite was designed to avoid consciousness, to abdicate sympathy.

Patriarchy Lite, to the contrary, honored and rewarded sensitivity, honored and rewarded critical consciousness. It was wholly in tune with the resistant, innovative spirit of gay camp, avant-garde art, and ethnic humor.

But for all of that, Patriarchy Lite still kept the focus on the boys.

BioShock Infinite has been justly criticized for its hamhanded handling of race, the Vox Populi’s justified war against white power, and the character Daisy Fitzroy. But what else should we expect? The game was never really about race, class, or imperialism. All that fustian about Wounded Knee, the Boxer Rebellion, Manifest Destiny, worker’s rights, and American Exceptionalism? Bait for the third act’s switch into bad old-fashioned family romance. It was always about Booker. It was always about Daddy.

Braid incisively anatomizes Tim’s neurotic, self-serving character. Further, as we piece together the game’s jigsaw puzzles, scan the books arrayed across cloud rooms, decode the allegory of mechanics and visual design, we come face to face with masculinist ideologies embedded in game genres and gaming culture. But think about what we have to do to get there. The counterintuitive, obdurate puzzles jibe with the precious, self-aggrandizing confessionals in those little books. As much as I enjoy the game, at times it feels like I’m in a writing workshop with that guy. (You know that guy, right?) Like BioShock Infinite, Braid assumes that the foibles of a petulant, manipulative, navel-gazing boy-man matter to the world. Matter as much as nuclear war. Seriously? Yes, very, very seriously.

How has the irony epidemic mutated in the Trump era? In some respects, it has entirely lost its sense of critical consciousness. Trump and his base are perfectly aware that their claims to moral superiority and historical destiny are full of shit, but they don’t give a shit about being full of shit. The fan boys who complain about comic books getting “political” embrace the abuse heaped upon them as a mark of their virtue. But irony has also fractured. The segmentation of the cultural market has divided ironists the same way it has segregated the connoisseurs of GMO-free burrito-bowls from the Triple Whopper crowd. And there are any number of people who have given up irony altogether, recognizing the way it distances us emotionally from the crimes of our moment. Those are the people who march and run for office. For those with no taste for patriarchy, be it lite or full-calorie, there are alternatives: movies, games, television, and comics that keep an eye on gender, class, and race without getting stuck on snark. But most of all, the privilege that allows someone to ironically cite sexual harassment is no longer getting away with it, at least not as much as it used to.

But the most welcome development in the irony epidemic is its reappropriation by the communities that did it first and best. This is exemplified by a segment that regularly appears on Late Night with Seth Meyers, “Jokes Seth Can’t Tell.” As Chance Solem-Pfeifer describes it, “Late Night writers Amber Ruffin and Jenny Hagel alley-oop the punchlines to shelved monologue jokes, or as Meyers puts it, ‘jokes that due to my being a straight, white male would be difficult for me to deliver.'” Here, the irony belongs to Ruffin, who is black, and Hagel, who is lesbian, and the subtext of Meyer’s privilege is brought right to the top. And though Meyers may still be in the center of the picture, he’s framed by Ruffin and Hagel. They aren’t just cited. They’re there.

But here’s the rub: the colonizer’s still in the middle. Though the self-pitying fanboys and aggrieved suburban white dads will tell you otherwise, it’s still a great time to be a straight, white cis-male with a premium education, marketable tech skills, thousands of hours of game play under the belt, and the dozen other privileges, big and small, of the white, heterosexual cis-male with a great smile and a way with words. A little guilt and self-consciousness sets it all off nicely.

It feels a lot like classic Patriarchy Lite. Run and gun, jump and smash, kill the boss, get the girl. But do it “critically,” do it “historically.” Do it in air quotes.