June 23, 2018

This is the eighth in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

(Spoilers)

Teaching and learning in the interface between media

As I explained in a previous post, my interest in videogame studies has evolved recently towards novels, short fiction, television series, movies, and graphic fiction that represent, in some way or another, videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. As a result, when I teach videogames, I try to create a dialogue between videogames and literary texts. This syllabus represents my first classroom efforts to do that, to energetically integrate the study of videogames as a powerful form of imaginative media into literary studies. In so doing, I hope to gain better understanding of how our society is making sense of the impact of videogames on how we think and feel about ourselves, technology, community, and play. And I hope to gain a better understanding of how the unique characteristics of videogames are enabling us to think about who we are, how we participate in our communities, how we might imagine ourselves differently.

In the first part of this multi-part post, I described the course overview, the core questions, the objectives, and the ludography and bibliography. Here, I delve into the week-to-week details of the first half of the course.

Note: This was a graduate-level course attended by masters- and doctoral-level students. We met once a week. If I were to adapt this syllabus for, say, an upper-level undergraduate course that met twice a week, I would probably cut a third of the readings.

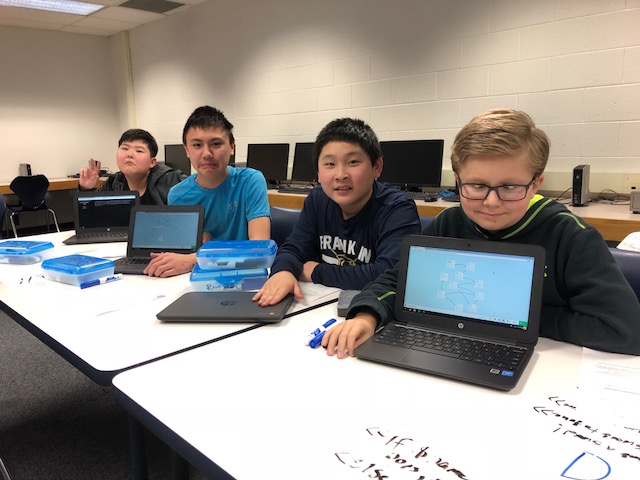

And one more, especially important note: I work with some of the best students in the world. The success of this course was due in part to a small group of graduate students who have worked with me intensively over the last couple of years as students, as graduate assistants, and as members of IUP’s Critical Play Union, a group that organizes scholarly and play events and that, currently, is leading interactive-fiction workshops at regional middle- and senior-high schools. And the rest of the credit goes to the group as a whole. My thinking and teaching evolved as a result of my time with them. Due to privacy policies, I can’t name them here, but they were brilliant.

Speaking of students, I surveyed them in advance to gauge their level of experience with videogames. All but one were experienced players, though their tastes varied widely. Only two had played indie, “queer,” or “serious” games. Only three had any experience with the scholarship and criticism of games—and that from taking a previous course with me or participating in the activities organized by our game studies organization, the Critical Play Union.

A couple of abbreviations you’ll find below: Chainmail Bikini (CB), Press Start to Play (PS2P)

UNIT 1: GAMES AND FICTIONS

The first unit of the semester focused on the relationship of games—understood broadly as rule-based interactive systems but also frameworks in which players play and experiences that can shape our identities and relationships—and fiction. Over several weeks, we approached that relationship from several angles, in a variety of contexts, and by playing games as well as reading and watching literature about games.

EVENING 1: KEY CONCEPTS AND GUIDING QUESTIONS

What we read:

Jesper Juul, Introduction to Half-Real

Bianca Batti, “Bridging the Gap: Literary Studies, Game Studies, and Where I Fit In”

James Paul Gee, “Pleasure, Learning, Video Games, and Life: The Projective Stance”

Maggie Siegel-Berele, “Battle for Amtgard” (CB)

What we played:

Davey Wreden, The Beginner’s Guide (play to completion)

What we did:

For our first meeting, I wanted to get students thinking about three things.

First, what Jesper Juul considers an essential aspect of the videogame medium: its “incoherence.” Normally, we think of the term “incoherent” as a negative. When someone is acting incoherently, it’s time to get them to the hospital or check their phone messages. Something’s wrong.

Juul uses the term differently. As he explains, there is a fundamental, even productive tension in videogames created by the lack of clear fit or cooperation among (1) rules and fiction, (2) the game and the player, and (3) the playing of a game and the context in which play occurs. He uses the example of Mario’s three lives. There is no narrative reason for Mario to have three lives—he’s just an everyday plumber with an outstanding vertical leap and thick skull. Players simply accept three lives as part of the game. The relationship between game and fiction is therefore “incoherent.”

For Juul, incoherence is a bit like what literary scholars call “suspension of disbelief.” But incoherence can also be about ludic literacy and technological convention. When we first start playing a game or play with a new type of game controller, for example, we are acutely aware of the lack of fit between our bodies and minds and the game we’re playing. Finally, incoherence can be an ideological or social tension. What is the connection between the moments when I’m playing a game and the moments when I’m grading papers or waiting in line for coffee? The essays by Batti and Gee, the graphic short story by Siegel-Berele (about her experience as a woman in the long-running fantasy battle game Amtgard), and Davey Wreden’s rather creepy videogame provided several ways to think about the distinct but overlapping dynamics of incoherence and how players negotiate them.

Second, I wanted to emphasize “fiction” as opposed to “narrative.” When we discuss videogames as literature, we tend to focus on storytelling. But not all games or works of literature tell stories. Juul focuses instead on the broader conception of “fiction” and I like that. “Fiction,” he writes, “is commonly confused with storytelling. I am using fiction to mean any kind of imagined world . . .” (122). Fictions are constructed by videogame designers, for sure, but they are also constructed by players as they play and by the larger culture in which play occurs. These fictions might be ideological (“There’s nothing sexist or racist or homophobic about the fact that most game protagonists are cis white males”) or critical (“I’m going to imagine Bro-Shep is gay”) or creatively (“I’m writing a poem where I ship Tracer and Pikachu”).

With this broader concept of fiction in mind, we can approach The Beginner’s Guide, for example, as a text that gets us thinking about the fictions that are constructed within games, as well as the fictions that players create to make games mean what they want them to mean. Fictions, in The Beginner’s Guide, are the tools used by some players to exert power over the stories that other people tell—and sometimes over those people, too. In contrast, Siegel-Berele’s short graphic story nests the in-game fictions of the battle game Amtgard within larger ideological fictions about gender and the ass-kicking women who are bored and annoyed by those fictions.

Third, I wanted to encourage us to think about videogame criticism as more than just analytic essays with endnotes. In her essay, Bianca Batti courageously explores the anxieties that can plague scholars who want to study videogames, especially those who work in universities and don’t have tenure. That honesty is complemented by an unshakeable commitment to reaching a broader audience, to get more people involved in the conversation about videogames, and to be involved in more conversations. That requires the scholar to use many voices and seek out unconventional platforms—blogs and “middle-state” publications, for example.

A page from Maggie Siegel-Berele, “Battle for Amtgard” (http://maggiesiegelberele.blogspot.com/2011/04/amtgard-in-two-pages.html)

Siegel-Berele’s story tells the story of women, both individuals and communities, being undermined by male privilege and successfully overcoming that oppression through the exercise of game skill and the creation of empowering feminist and queer coalitions. James Gee underlines the importance of pleasure and learning and the need to find ways to effectively talk about them. And, finally, Davey Wreden alerts us to the hazards of pleasure and the ethical swamps that critics enter when they attempt to intervene and control the meanings of videogames and the fictions they construct.

EVENING 2: WHAT IS A GAME?

What we read:

Jesper Juul, Chapter 2 from Half-Real

Rachel Ordway, “Choose Your Own Adventure” (CB)

What we watched:

Westworld (episodes 1 and 2)

What we played:

Tom McMaster, Horse Master: The Game of Horse Mastery

What we did:

As the title of the evening’s lesson suggests, we spent our time figuring out what makes a game a game. That’s a surprisingly complicated, appetizingly philosophical question, just the thing for a bunch of nerds who love to complicate and philosophize, which we were! As with our first evening, we relied on Jesper Juul for the framework and critical terms, then applied them to texts that illustrated his concepts but also complicated them.

Juul draws a line between videogames and what he calls the “classic game model.” The latter refers to the way “games have traditionally been constructed” for the last 5000 years (23). A “classical” game has the following:

- Rules

- A variable, quantifiable outcome

- An outcome that is defined by a particular set of qualities: “The different potential outcomes of the game are assigned different values, some positive and some negative” (36).

- Player effort.

- Player attachment to the outcome. We care about what happens while we play.

- Negotiable consequences: “The same game . . . can be played with or without real-life consequences.” (36)

In addition (and following through on his three-part definition of “incoherence”), he argues that any good definition of a game needs to account for “(1) the system set up by the rules of a game, (2) the relation between the game and the player of the game, and (3) the relation between the playing of the game and the rest of the world” (28).

Videogames deform the classical model in several ways. For one, the computer often does much of the work of defining and enforcing the rules as well as determining game outcomes, thus removing from play the palpably human work of enforcing the game’s system—work that belongs to everyone at the table or a duly appointed official. Further, the power of computers allows game developers to construct far more rule systems than a conventional game would accommodate. We think here of the multiple interlocking rule systems of FIFA 18, for example, that govern the physics of ball movement, weather, field friction, avatar performance, and the enforcement of rules. Additionally, videogames sometimes do not have definable endings or outcomes. World of Warcraft, for example, not only never really ends, but allows the players to define what they want to do and how they want to do it forever and ever and ever . . .

(By the way, did you hear about the new expansion? Supposed to be great!)

The readings and games for the evenings were, in various ways, fictions about games, stories that explored how games work and how they fail to work. Rachel Ordway’s comic “Choose Your Own Adventure,” for example, tells the story of three kids who really want to play roleplaying videogames but aren’t allowed to, so they make up their own game using the toys and boardgame pieces they find in their basement. Jon Bois’s 17776 deploys the conventions of speculative fiction, altering two fundamental physical laws to make the storyworld work differently, and then explores the impact of that alteration on how we play and enjoy the game of football. Tom McHenry’s interactive fiction game Horse Master nests a simple pet simulator game in a fictional spec-fic world in which fame and fortune can be won by cultivating, week by week, the perfect beast for an international competition. But to do so, the character commits themselves to poverty, addiction, and the sacrifice of the creature they’ve raised. With the first two episodes of Westworld, we worked to identify the several kinds of games cooked into the amusement park and the several kinds of gamers who visited it.

This session also marked the first steps we took towards what might be called a “ludological” approach to literature. We asked ourselves, how might an understanding of the principles and dynamics of game play—whether classic or videogame—allow us to better understand the formal principles of novels, movies, television shows, poems, and plays, even if they weren’t in any way “about” games?

There’s a moment in Horse Master, for example, when the player is allowed to stop making the day-to-day granular decisions about which characteristics of their horse they way to improve. Instead, they simply follow the recommendations of the game itself. McMaster’s self-conscious incorporation of this common “metagaming” strategy is a smart comment on the ways players can evade the effort required by games and, in so doing, diminish the ethical issues that a game like Horse Master raises.

Similarly, because we were able to identify the several kinds of games built into the Westworld amusement park, the different kinds of players who visited or worked in it, and the games the series was playing with us as viewers, we were able to develop a more intensive and detailed understanding of the themes, conflicts, and questions the series was exploring.

EVENING 3: GAME < – – – – > FICTION 1

What we read:

Jesper Juul, Chapters 4 and 5 from Half-Real

What we played:

Kim Swift, Portal

Michael Townsend, Amir Rajan, A Dark Room

Anna Anthropy, Dys4ia

What we did:

Having established what a game is and how videogames both follow and diverge from the “classical” model, it was time to focus on “fiction.” Again, we relied on Juul to guide us into the big questions and to avoid making overly broad claims. I appreciate his point that the relationship of rules and fiction in games is “complementary, but not symmetrical” (121). Even more, I find useful his point that the players of games play a central role in that fiction. It is the player who, through the performance of play, provides the “coherence” between rules and fiction. This is true of all fiction, of course. There is no work of fiction that achieves a complete representation of the world it portrays: “all fictional worlds are incomplete” (122). But the particular nature of a videogame’s incompleteness puts a special responsibility on those who play them to imaginatively fill in the gaps.

That responsibility comes in many forms depending on the kind of game we’re playing. When we play chess or poker, we are in a world where royalty and royal factions exist, but we generally don’t do anything with that story stuff. When I play Super Mario Galaxy (2007), I’m delighted by the worlds I visit and take seriously Mario’s duty to restore power to Rosalina’s Comet Observatory, defeat Bowser, and rescue Peach, but I could imagine any number of other storyworlds that could justify the labor of making an avatar run and jump for very different reasons (looking at you, Portal). When I play Dragon Age: Inquisition (2014), I can, if I wish (and I do wish, I do!) dive deep into the game’s lore, spend hours developing friendships and romances with non-player characters, even make decisions that aren’t in my best interest strategically but that make sense in terms of my character.

And the way we manage that responsibility depends on how the fiction of the game is designed and communicated. Juul: “A game cues a player into imagining a fictional world,” and they do so in a variety of ways (134-35). He counts the following: graphics, sound, text, cut-scenes, packaging, haptics, rules, player actions and time, and rumors (134-39).

We spent a lot of time on that last bit. By “rumor,” Juul intends the various kinds of information a player might get from sources outside the game—from friends, magazines, and the like. This is where Juul’s book shows its age. Published in 2005, Half-Real’s analysis of the rules-fiction dynamic doesn’t account for the intensely social, cross-platform, networked nature of game play. As I argued in a previous post, when we play videogames, we don’t just play the game itself, but play a network of texts, and play not only as players, but as forum respondents, cosplayers, live streamers, students, and so on. Indeed, I would argue that we can play videogames even when the screens and computers are turned off.

I chose the games for the night—Portal, A Dark Room, and Dys4ia—because they constructed the relationship of rules and fiction in distinct ways and rules/fiction ratios. Portal, for example, would be a great game even without the hectoring sarcasm of GLaDOS and reminders that the cake is a lie. In contrast, the game play of Anna Anthropy’s Dys4ia is simple, even rudimentary. The center of the player’s experience of that game concerns how we construct a coherent relationship among the various minigames and how we come to recognize the subjectivity of the designer. Dys4ia’s gameplay is found in the meta. Finally, A Dark Room lures us into a complex set of resource-management and –development procedures, the fun of which proves surprisingly effective as a way to obscure the brutality of what we’re doing and, in a twist ending, recognizing who we are.

EVENING 4: GAME < – – – – > FICTION 2

What we read:

Chainmail Bikini, ed. Hazel Newlevant

What we did:

The final evening of our first unit was dedicated to identifying, exploring, and evaluating the critical methods that might be used to criticize works of literature that represent videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. Unlike previous evenings, we dedicated ourselves to literature on the printed page, the short graphic stories about women players in Hazel Newlevant’s Chainmail Bikini anthology.

We held on tight to Juul’s concept of incoherence, which was proving surprisingly useful—particularly when it was grafted with the tools of literary criticism. I defined the following as useful applications of incoherence in the study and criticism of videogame literature:

- To help us better understand the cognitive and performative aspects of videogame play.

- To help us more precisely identify the relationship between rules and fictions in a given game and be more attentive to how each fills in the gaps of the other.

- To enable us to identify shortcomings in games, whether that’s due to poorly designed rules, procedures, and mechanics or a narrative that isn’t told well. And by poorly, we included narratives that affirm the limited perspectives of straight, white, European men or that promote concepts of play that affirm racist, homophobic, misogynist, elitist worldviews.

- To promote innovative theorizing. Incoherence is where we can locate particularly significant forms of ideological and performative work. Particular forms or moments of incoherence can inspire ways of defining videogame genres in ways that run against the grain of conventional marketing schemes.

- Finally, incoherence is one way we can gain insight into the important social, cultural, and creative work of videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture.

But before we got to work theorizing videogame literature, we had to deal with a more fundamental issue. There is very little written on the subject of literature about videogames. And what has been written doesn’t address the kinds of “big picture” questions that must be asked and answered any time we attempt to define a body of literary texts as a genre:

- What are the specific characteristics of “videogame literature”?

- What are the common themes, questions, and issues explored by “videogame literature”?

- How does the concept of “videogame literature” account for cultural difference, historical change, audience expectation, the economic structures of production and reception, and so on?

This was the evening that I introduced the seven tropes of videogame literature, which I’ve covered in detail in a previous post.

A significant part of the class meeting was given to small teams who were tasked with tracking those seven tropes across Chainmail Bikini’s diverse stories and then sharing and developing discoveries. I don’t want to take up space going over the details of what the students found and what we generated afterwards, but I was thrilled to discover that the tropes I had defined proved to be effective analytic tools, particularly when used along with feminist and queer theory (which were the obvious ones to use with stories that focused on women and girls, straight and otherwise). Regardless, I urge you to check out Chainmail Bikini and try out the tropes for yourself! I’d love to hear about what you discover!