September 25 2022

This is the eighteenth in a series of posts dedicated to works of playful literature—novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another games, game players, and game culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, though one that’s more focused on videogames rather than games more generally, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

This post compiles the reviews I’ve written on Letterboxd about car-racing movies released between 1960 and 1980, posted in the order I wrote them. I started watching these movies because I wanted to dig into sports movies that were off the beaten track, if you will, of most scholarship (i.e., movies about baseball, football, soccer, basketball). But before I dove in, I needed to cut my list—I wanted some historical scope to my viewing, but I didn’t have time to watch the 130 movies listed on IMDB under the tag “car racing”—and I knew there would be more I’d discover as I did my research.

I decided to focus on the 53 films listed on IMDB released between 1960 and 1979, a decision driven by my interest in a period when sports, games, and movies underwent significant and concurrent change, but also a period in which audiences could watch movies in diverse contexts. I haven’t watched every movie on that list and only a dozen or so released after or before, so my understanding of the history of the genre is limited and most of my comments here won’t be about history or will be a theoretical stretch.

The movies I watched represent a mix of the classic, the oddball, and the available. They vary in terms of the kind of car racing they portray: Grand Prix, drag racing, stockcar racing, endurance racing, the figure eight, etc. And they vary in quality, budget, and audience, from luxe affairs like Grand Prix (1966); grindhouse exploitation flicks like Death Race 2000 (1975); gritty noir tales like The Killers (1964); Lynchian death drives like Pit Stop (1969); middle-of-the-road melodramas like Winning (1969); documentaries like Seven Second Love Affair (1965) and One by One (1975); and bubblegum pop like Speedway (1968), Bikini Beach (1964), and the Herbie the Love Bug series (1968, 1974, 1977)—and no, quality does not correlate with budget or audience.

I will synthesize my thoughts on these movies in a future blog post, titled “Fast Cars, Macho Men, and Capitalism in Drift: American Car Racing Movies of the 1960s and 70s.”

One by One (1975)

The opening moments are something out of a horror film, the footage raw, grainy, a man running towards an F1 race car, a race marshall we realize, then two more marshalls across the road, a horrible droning sound is the only soundtrack, then wait . . . what? No one could survive that, could they?

This is an intense, intensely stylized exploitation documentary.

Director Claude du Boc assembles a hyperactive film representing the deep, dangerous, obsessive, horny weirdness of F1 racing in the 1970s.

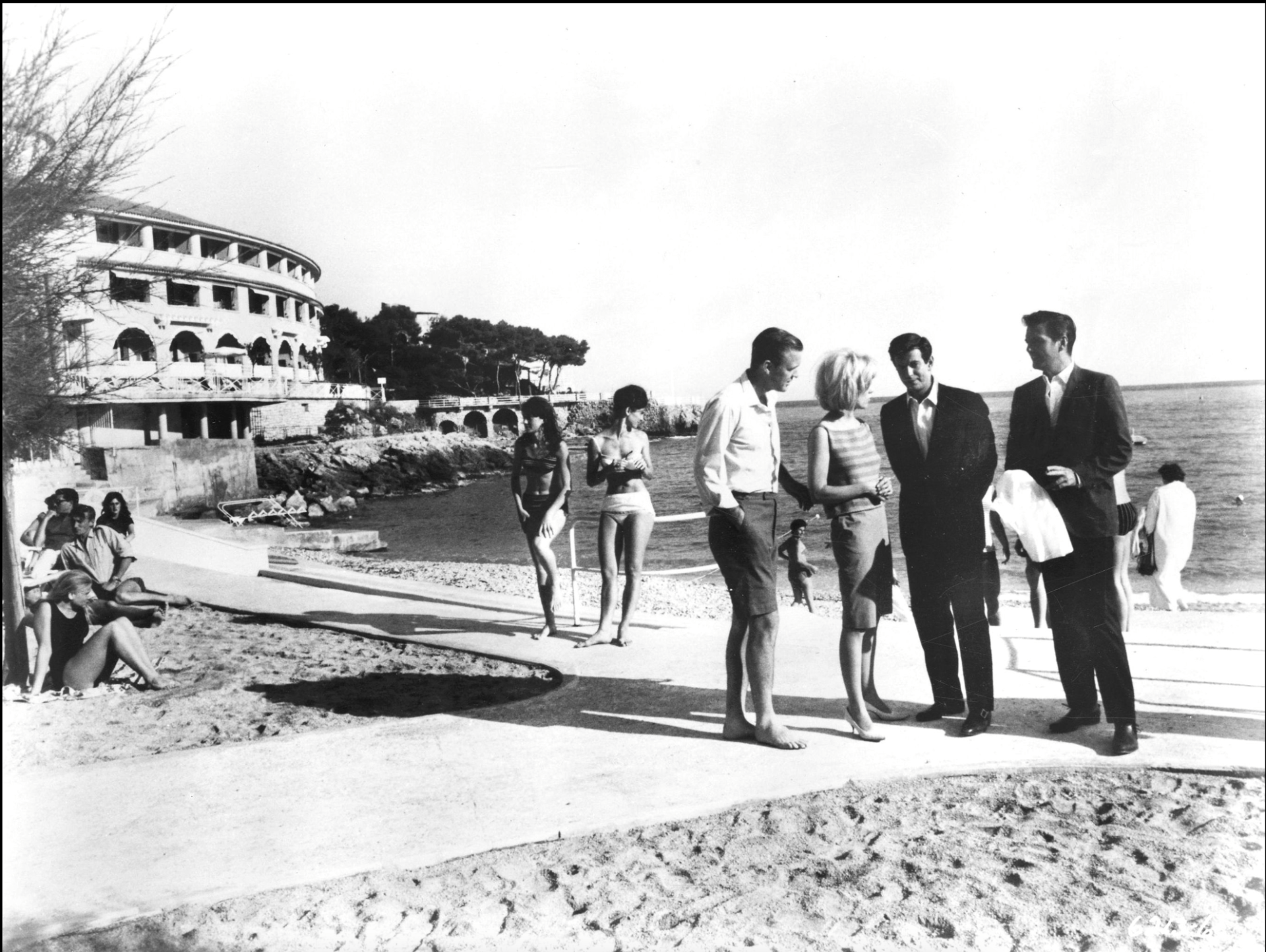

An early sequence reads like an experimental pop film: a montage of road signs, track signs, paddock signs, medical center signs. Another sequence takes us to a beach where the soon-to-be-bisected François Cevert frolics with a topless woman as the camera lingers over the tops of other topless women whose consent to be filmed is likely legally dubious. Meanwhile, Stomu Yamashta’s score races alongside, veering from psychedelia to synth-amplified orchestral Verdi to hard rock to somethings else.

Kudos to narrator Stacey Keach for keeping a straight face and a steady baritone as he intones the most exquisitely horny bro-prose.

A truly weird film, sometimes genuinely beautiful to just look at and listen, as long as you accept that it’s about to go off course and immolate in pervy, death-obsessed voyeurism.

Le Mans (1971)

To quote Brian Tallerico, “Starting a film without a script isn’t the best plan of action.” While it advertises to be a sports drama, it’s essentially a documentary–at times, a truly spectacular documentary–of the 1970 24-hour Le Mans race. At which, to some arguable degree, a movie happened involving Steve McQueen.

That part of the movie is reticent, detached, oblique, mostly shots of people staring off into the middle distance or strolling about the race grounds. The climactic scene between McQueen’s Delany and Elga Andersen’s Lisa, both of them traumatized by the death of a racer the year before, is so cool, it’s sculptural. It lands the yearbook-worthy quote, “Racing is life. Anything before or after is just waiting.”

It’s René Guissart Jr. and Robert B. Hauser’s color-saturated, kinetic cinematography that’s the star here. Director Lee Katzin has them cover the entire Le Mans scene, from the corny carnival attractions to the packed campgrounds to the impossibly handsome drivers to the twists of a spanner. The cars are just so sleek and cool and hard.

There’s a pop sensibility here shared by Claude du Boc’s weird, frenetic documentary ‘One by One,’ a shared affection for the look and feel of the sport that could care less for the people involved. I kind of like that McQueen doesn’t care about the backstory any more than I do. If we’re not racing, we’re waiting for racing.

Ford v Ferrari (2019)

‘Ford v Ferrari’ is a movie acutely aware of its history, and that history is pure cornball. This is one of the reasons why I’ve included this movie, released in 2019, in this compilation of reviews.

To begin with, it’s a movie about the history of car-racing, telling the tale of a fateful moment in the European and U.S. automotive industry and its glamorous, greasy research-and-development arm. It’s got all the expected signifiers of ye olde 1960s in its carefully curated art direction, costume design, and music, minus the smoking, the Asian automotive industry, and Black people.

It’s also a movie about the history of car-racing movies. DP Phedon Papamichael cites two of the classics—’Grand Prix’ and ‘Les Mans’—as source code, providing the style and vocabulary to render the racing visceral and dramatic and coat it all in the look of big-budget, big-event 1960s cinema. And, not surprising for a specialist in cinematic masculinity like director James Mangold, it owes an equally evident debt to stories of sweat-slicked STEM-focused nerdboy masculinity like ‘The Right Stuff’ and ‘Apollo 13’, but also ‘The Martian,’ released just a couple of years earlier. When did Matt Damon become the spokesman for all that?

It’s a three-hander, each character representing a particular conflict between sexy masculinity and late capitalist cycles of innovation and retrenchment. We’ve got Ken Miles, nickname Bulldog, WWII veteran, grease monkey, speed demon, holder of principles, good family man always with a British-ism ready to hand. Then we’ve got Carroll Shelby, former grease monkey and speed demon who now designs and sells cars while channeling Tommy Lee Jones. Carroll is in uneasy détente with the industry, though his indy sensibility is running up against economic necessity. The third character is not a character per se, but an omnipresence, the Ford Motor Company, a composite monster of smartly cut suits, conference rooms, factories, and baritone corporate speak.

Ken and Carroll are old fighting friends, their bond cemented by the belief that cars are philosophy in machine form. This point is hammered home with a voiceover that is repeated twice, in Tommy Lee Jones, so we know it really matters: “There’s a point at 7,000 RPM . . . where everything fades. The machine becomes weightless. Just disappears. And all that’s left is a body moving through space and time. 7,000 RPM. That’s where you meet it. You feel it coming. It creeps up on you, close in your ear. Asks you a question. The only question that matters. Who are you?”

Which is where the movie’s historical sensibility is most evident and strange. The car-racing movies of the 1960s and 70s often portray racing as an existential activity—to race is to defy death; to be a true racer is to escape all mundane and earthly bonds, to transcend the contingencies of love and engineering through pure speed. Sometimes, the “existentialism” of the car-racing movie is tacit, like the rebel-yell masculinity of ‘Thunder in Carolina’ or ‘Eat My Dust!’; sometimes articulate and dialogical, like ‘The Young Racers’ or ‘Grand Prix’; sometimes reduced to absurdity like ‘The Wild Racers’ or ‘Pit Stop’; sometimes downright mystical, like ‘Vanishing Point.’

‘Ford v Ferrari’ does it with cornball. The guys with the British and Texas accents (the synecdoches of rugged individualism in the face of bureaucratic collectivism) have their feelings hurt by the corporate villains, but come out the other side as good friends who get to keep making cars (and we might remember that Ford’s about to get its ass kicked by OPEC and Honda lol). They’re the ones who get a nice hot cuppa of fast-car existentialism at the end, Ken going out in a cloud of dust and fire, and Carroll and Ken’s son making crystal-clear to the audience that the most important thing about racing is the friends we make along the way. Also, custom-designed sport cars.

Grand Prix (1966)

I watched this as the third entry in an impromptu trilogy of “serious” European car racing films, the first Claude du Boc’s horny 1975 documentary ‘One by One,’ the second Steve McQueen’s hyper-cool ‘Le Mans’ of 1971. Each of these advertise their realism and authenticity, whether due to their documentary elements, their access to drivers and the broader racing scene, or their unconventional, innovative way of telling a story about racers and racing.

‘Grand Prix’ is a big-budget extravaganza filmed for what was the cutting-edge immersive technology of the mid-1960s, Cinerama. Cinerama was an ultra-widescreen process in which 3 cameras were projected onto a single screen whose edges curved towards the audience. Cinerama screens could exceed 100 feet in length and 35 feet in height and their theatres could hold 1000 ticketholders. ‘Grand Prix’ was filmed and projected in Super Panavision 70, which eleminated the need for 3 cameras without losing the immersiveness.

It must have been mind-blowing to see in its intended format, engulfed by the screen in a way contemporary IMAX can’t get near. Director John Frankenheimer and cinematographer Lionel Linden pressed and invented and risked life and limb to capture some of the most visceral road action you’ll ever see on film, rivaling ‘Mad Max: Fury Road.’ It’s the best of the three movies. But that’s also due to the Oscar-winning editorial work of Fredric Steinkamp et al. I find ‘Le Mans’ confusing when it comes to tracking the positions of the racers. That’s never the case here, especially on smaller, landmark-heavy courses like Monaco.

The story’s pretty good, too, a glamorous quartet of racers at different stages of their careers, each contending with their feelings for a glamorous, emotionally and financially independent woman (Jessica Walter, Eva Marie Saint, and François Hardy). Spoiler alert: only one of them works out in the end, and it’s probably not the one you want.

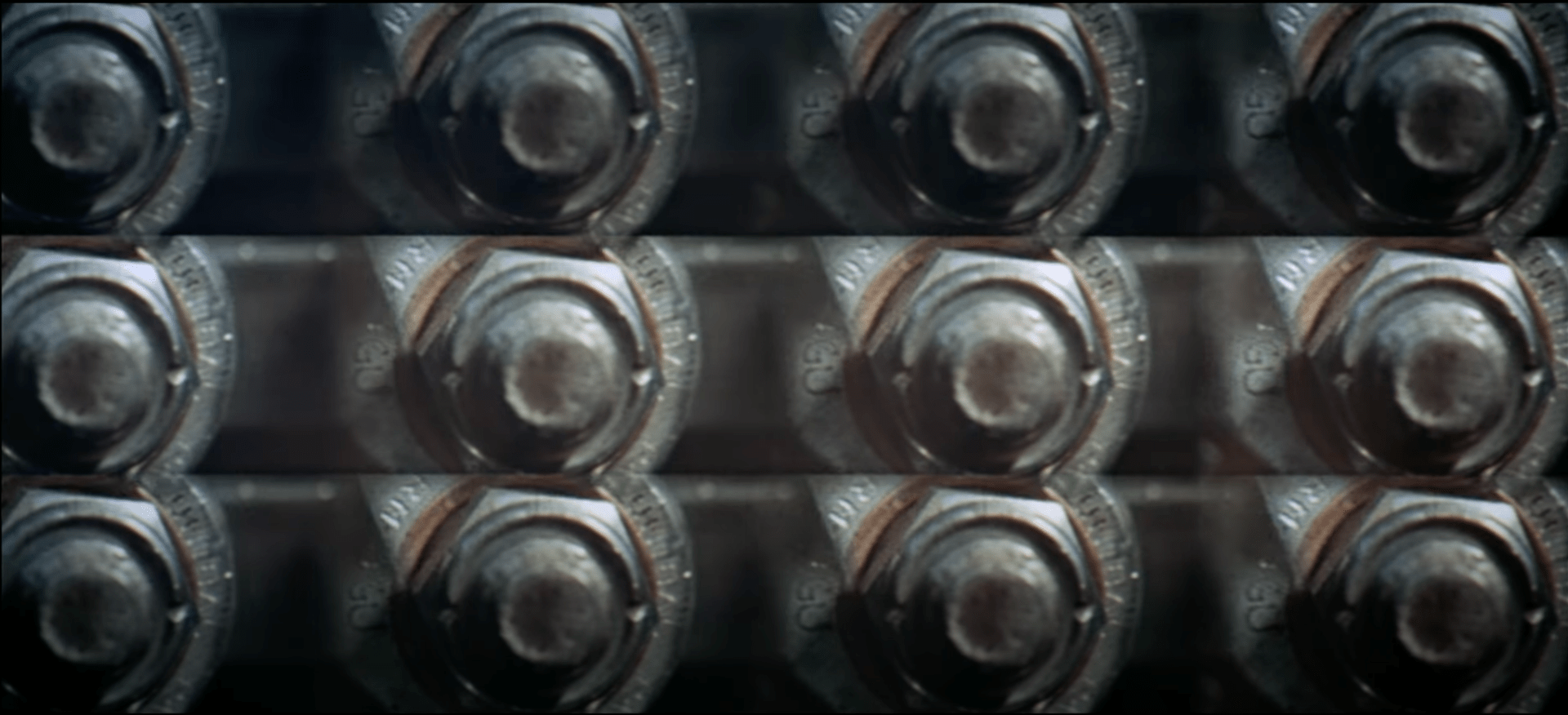

But what struck me the most about these three movies–something that du Boc’s film does to perfection–is the Pop Art sensibility. All three are fascinated by the vivid colors and graphic environment of European racing culture. But if ‘One by One’ and ‘Le Mans’ capture the muchness through a focus on the graphic quality of cars, signage, and the collision of elite and popular cultures, ‘Grand Prix’ goes for the serial approach. Saul Bass designed over a dozen split-screen sequences that express, in his words, “muchness.” It has an Andy Warhol quality, recalling the multiple Elvises and Marilyns and, of course, car crashes.

The multiplication of images here–of tail pipes and ratcheting wrenches and racers and more tail pipes and cars zooming across space and spectators–immerses us into the culture of reproduction that’s the essence of Grand Prix racing. A combination of braking and acceleration practiced again and again, victories achieved race after race, championships achieved year after year, automobiles manufactured to exact specification–the multiplication of images mirrors the multiplication of gestures and parts. Our eldest protagonist, played by Yves Montand (one of four, identical to the rest except for his age), is the one most aware of the existential costs of repetition, having lost friends and rivals to crashes over his years on the circuit. There’s a remarkable shot of him in his trophy room, visually engulfed by dozens of identical posters, trophies, and championship wreaths. He’s not trapped, but he can’t get out, a message underlined near the end of the film, when his ex-wife slips into the story and the back of the ambulance.

But seriously: get your biggest screen and your best speakers for this one. The opening race at Monaco and the closer on the banked curves of the pre-1969 Monza track are genuinely thrilling.

Also, I’m pretty sure this is where Adam Ant got his “Don’t drink, don’t smoke, what do you do?” lyric for ‘Goody Two Shoes.’ And, yes, subtle inuendo follows.

Fast Company (1979)

Heartfelt is not a word I’d use to describe any other David Cronenberg movie, but it applies here. This is a straight-down-the-middle B-movie that pairs with any of the dozens of hard-rockin’ guy-centric car-racing flicks of the 1970s.

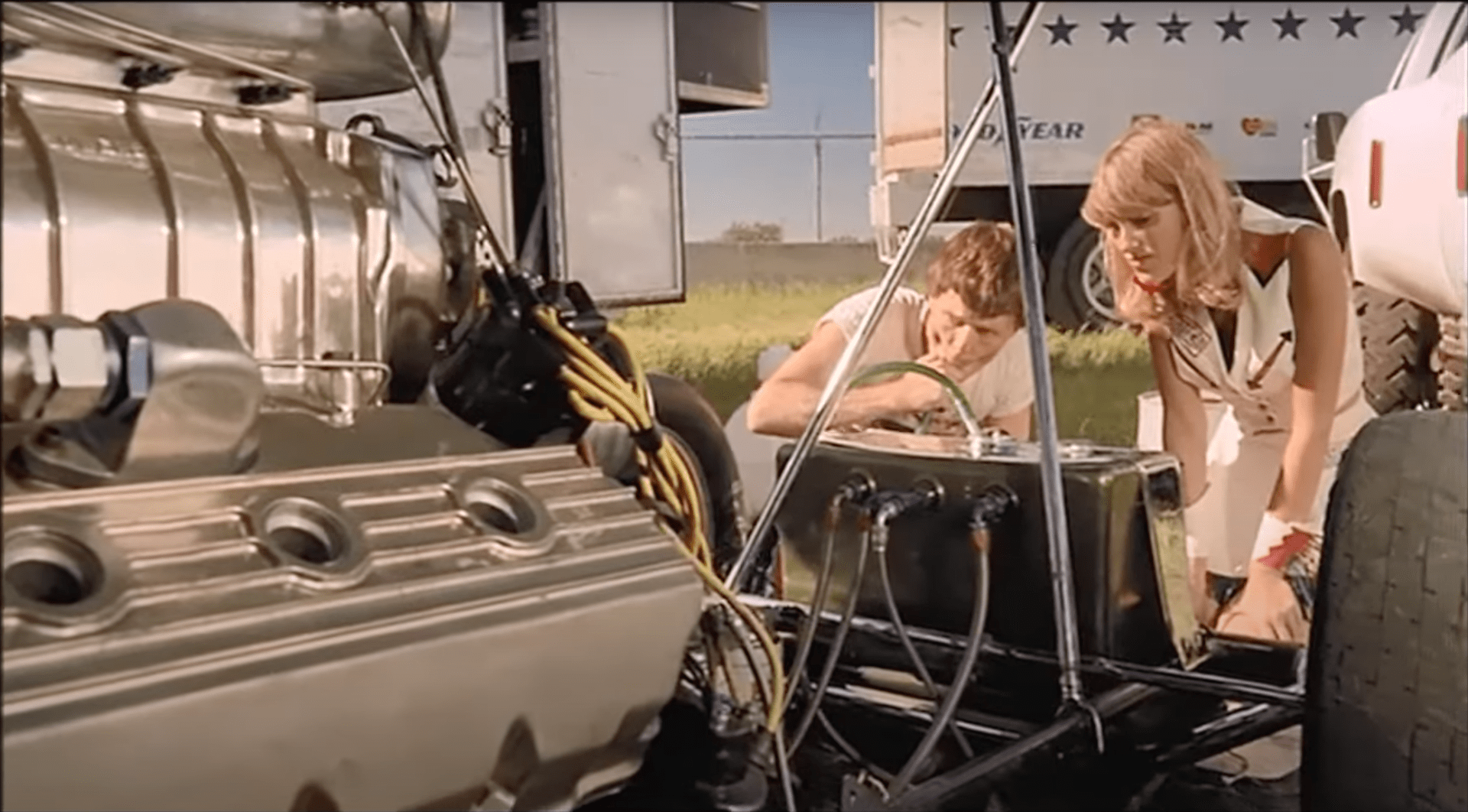

But it’s not an outlier in the Cronenberg filmography, as some have commented. The focus on weird, obsessive, no-apologies subcultures is as evident here as it is in, say, ‘Crash’ or ‘Videodrome.’ And there’s a scene just past the one-hour mark that is pure Cronenberg machine-horniness. The Fred Mollin score goes full sexy rock ballad as manly hands install and tighten and lube and a whole bunch of other stuff. Then there’s the scene where Billy cracks open a can of motor oil and pours it over the chest of one of the two high-heel-wearing hitchikers he picked up earlier in the day. “My boyfriend will kill me,” she purrs. “He hates FastCo.”

But it’s not an outlier in the Cronenberg filmography, as some have commented. The focus on weird, obsessive, no-apologies subcultures is as evident here as it is in, say, ‘Crash’ or ‘Videodrome.’ And there’s a scene just past the one-hour mark that is pure Cronenberg machine-horniness. The Fred Mollin score goes full sexy rock ballad as manly hands install and tighten and lube and a whole bunch of other stuff. Then there’s the scene where Billy cracks open a can of motor oil and pours it over the chest of one of the two high-heel-wearing hitchikers he picked up earlier in the day. “My boyfriend will kill me,” she purrs. “He hates FastCo.”

It’s corny fun, though Mark Irwin’s cinematography and Carol Spier’s art direction are spiked with moments of striking beauty. Seriously, there’s a shot of John Saxon walking away from a Cessna as the sun sets behind him that is just gorgeous. And William Smith’s performance as Lonnie “Lucky Man” Johnson is a classic tired-but-not-going-to-quit macho-man performance.

I think I just argued myself into giving this movie another star . . .

Speedway (1968)

Elvis plays a successful NASCAR racer with a penchant for generosity. Bill Bixby plays his best friend and agent with a penchant for spending his best friend’s money and violently harassing every woman who comes within arm’s reach. Nancy Sinatra plays an IRS agent who has come to the conclusion that she should give up acting.

‘Speedway’ is a racing movie only in the sense that racing provides visual flavor and roary, crashy interludes for the screwball comedy that fills the rest of the 90 minutes. To its credit, though, racing figures more significantly in the plot and design of the film than in, say, ‘Bobby Deerfield’ (1977). There’s something genuinely charming about the Speedway Hangout with its brightly colored convertibles/tables and go go girls. Credit to production designers Leroy Coleman and George W. Davis for recognizing the graphic potential of racing ads, posters, and other signage.

Vanishing Point (1971)

As much a fantasy epic as it is a racing movie, ‘Vanishing Point’ features top-tier stunt driving across an ethereal, unforgiving American Southwest, a kind of kinder, hippie-er less-anxious-about-the-end-of-the-Anthropocene version of ‘Mad Max.’

Barry Newman plays Kowalski as a stoic, speed-fueled Sisyphus, boulder replaced by a far better handling white 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T, a classic muscle car. His quest is simple: drive the car from Denver to San Francisco in three days, avoiding the police and sleep. His spiritual companion is a blind DJ named Super Soul, who broadcasts out of a dusty little one-street town with a giant broadcast antenna. Cleavon Little plays Super Soul like a shaman and his subplot–trying to keep Kowalski abreast of the current state of the police and his soul’s salvation–keeps K’s rugged individual anchored to social reality and a first-rate soundtrack.

As he drives, consuming speed to keep him going, the story becomes more and more dreamlike. The conclusion is kind of shattering, but also perfect.

‘Easy Rider’ meets ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner’?

‘Smokey and the Bandit’ meets ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’?

Did I mention Charlotte Rampling appearing out of nowhere with high-level joint-rolling skills?

Bobby Deerfield (1977)

“Is it your rabbits? You found them?”

In his review of the movie, Roger Ebert thanked God that this wasn’t “a racing picture.” And he’s exactly right. Though Pacino’s character is a Formula 1 driver who regularly wins and never crashes, there’s little else to indicate that driving is what he does for a living. And there’s little in his character that suggests he’d be the type of person who would want to face death behind the wheel of a race car as opposed to any other death-defying professions such as bull fighter, trapeze artist, or old man in fishing boat north of Cuba.

The two racing sequences that bookend the film are desultory and fail to do the one crucial thing that any fast-car film must do: show the character of the driver through the driving. I expected more from director Sidney Pollack, cinematographer Henri Decaë, and editor Fredric Steinkamp. We don’t get the sense that Bobby drives with the absolute control he desires, that he approaches any other aspect of his life with that same drive, or that the crash he suffers was due to his growing willingness to be honest and open about his emotional life.

But that’s not the point of the movie. This is a gauzy, glamorous romance movie between two people facing death, the other an early incarnation of the manic pixie dream girl who, as the rules of said dream girls require, enables the sad boy to discover his soul.

An additional half star for Al Pacino’s truly cringey impersonation of Mae West. Yes, you read that correctly.

The Killers (1964)

“A man stood still while we burned him, and I’d like to know why.”

As part of a research project on the representation of games and sports in literature, I’ve been watching movies about racing and other speed-centered sports. No, this isn’t a racing movie like ‘Grand Prix’ or ‘Greased Lightning’–racing isn’t central to the plot. However, unlike ‘Bobby Deerfield,’ racing in this movie matters to character and design.

‘The Killers’ is a classic noir tale about a pair of ruthless killers played by Lee Marvin and, in a deliciously unhinged performance, Clu Gulager. It’s what those two do that forced the producers to turn what was supposed to be part of the prestigious NBC Project 120 television series into a movie. When they beat up a blind woman in the opening scene, you know you’re in for a ride, though top marks for improvisatory violence goes to the scene where they steam a guy alive in order to get him to talk. But it’s their first kill that gets the movie rolling: an ex-racer who, when the guns are pointed at him, doesn’t try to speed away.

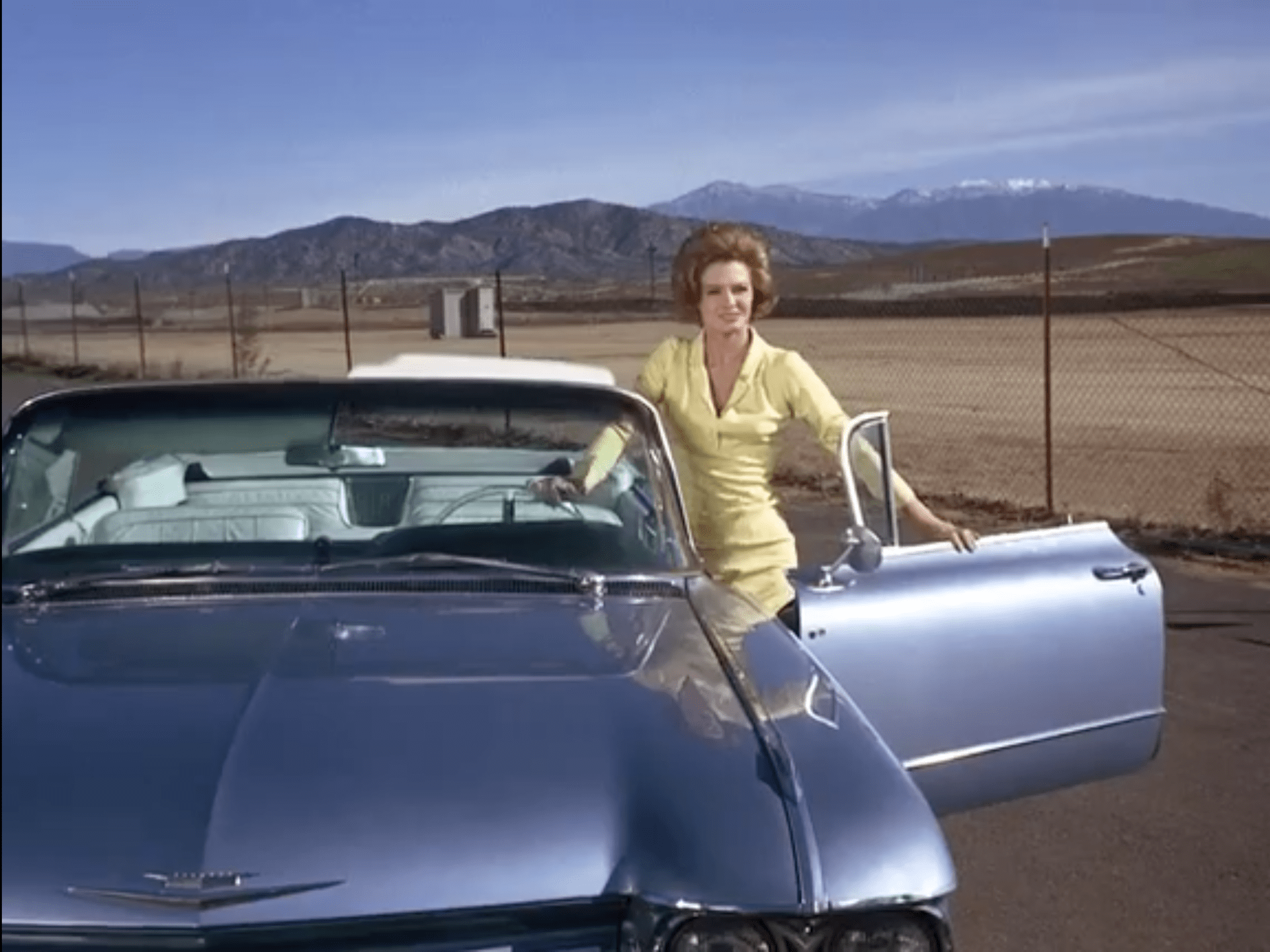

Frankly, most of the racing scenes are pretty desultory, with all of the close shots of John Cassavetes’ Johnny done in rear-screen projection (apparently, he couldn’t drive worth a damn). However, director Don Siegel and designers Frank Arrigo and George B. Chan capture the grease and grit of garages and downticket race tracks. And they do some really clever things with color, notably with Angie Dickinson’s wardrobe, designed by Helen Colvig. We first see in her in a canary-yellow dress (Caution, Johnny!), later in a white dress with a red ribbon accent (with Cassavetes in foreground cast in a vibrant red, doing his best to see the signs), finally in a green dress when she’s at her most vulnerable.

But what really makes this a movie about cars and racing is the sense that the machinery is constantly on the verge of crashing or breaking and all the characters are doing their best just to get around the next corner without getting killed. Which, unfortunately, almost all of them fail to do.

The Speed Lovers (1968)

William F. McGaha wrote, directed, and starred (though doing none competently) in this film about ambition, temptation, and loyalty on the NASCAR circuit. Though the poster advertises real-life champion Fred Lorenzen as the star, he plays a minor role, the moral paragon to McGaha’s Scott Clayton.

The real fun is the villain, Pinkerton Bentley, with his sunglass-wearing thugs and bouffanted bevy of international beauties. His evil plan doesn’t make a bit of sense, but he’s enjoying every machinated minute of it.

Red Line 7000 (1965)

Though generally agreed to be one of his lesser films, ‘Red Line 7000’ is still a Howard Hawks film. The dialogue, chemistry, and melodrama purrs along as one would expect, though the plot, as Hawks himself admitted, was too tangled to sustain dramatic momentum. It looks great, too. Milton Krasner shot part of it before being replaced by Haskell Boggs. Edith Head designed the costumes. And it takes place at a swank Holiday Inn, giving the whole a bit of a “it’s happy hour somewhere” hangout movie vibe.

It’s reminiscent of another racing melodrama, ‘Grand Prix,’ released the next year and to much greater (and deserved) fanfare. Both tell the stories of three drivers at different stages of their racing careers negotiating the racing circuit and troubled love. Unlike ‘Grand Prix,’ the racing scenes generally lack authentic drama. Yes, there are plenty of gasp-inducing crashes, but also plenty of rear-screen projection. But the fundamental problem is that Hawks doesn’t succeed with the two other things a sports movie has to do besides capture the intensity of the racing action: make moments of competition central to the drama and make athletic performance an expression of character.

There’s still a lot to like in the melodramatic tangle. James Caan, in one of his first film roles, is underutilized, but magnetic. Laura Devon is a knockout as Julie, the sister of the team’s director (the first of two roles involving men who suffer violent amputation of their hands). I’d argue there’s a coded queer relationship between Holly and Lindy, co-owners of a popular lounge. It’s brief, Holly goes straight at the end, but the relationship makes thematic sense only if it’s a mix of business and romance.

I’m stretching, for sure, but a queer reading does add a dash of irony to the ending. “It’s a hell of a way to make a living,” Holly says to Gabrielle and Julie as we watch A.J. Foyt’s car lose its brakes and tumble end over end into the infield.

The Young Racers (1963)

To pull off a good racing movie, you need to do three things:

1) Communicate the intensity of the sport;

2) Make the sport central to the story and the production design;

3) Make the driving an expression of character.

It’s not an easy trick. ‘Le Mans,’ for example, nails (1) but the plot is shapeless (2), and Steve McQueen’s performance is stoic to the point of inexpressivity, so the connection between character and athletic performance fails (3). The Elvis movie ‘Speedway,’ in contrast, lands them all. (This does not mean that ‘Le Mans’ a worse movie than ‘Speedway,’ as there are many other factors to consider.)

‘The Young Racers’ is a top-tier car racing movie, among the best of the genre. Director Roger Corman’s command of his craft is evident throughout, R. Wright Campbell’s script is philosophical without feeling phony, and Floyd Crosby’s camerawork is no-nonsense and not a rear-projection screen in sight. The racing footage has a visceral, documentary feel and while onboard camera shots are infrequent, they’re thrilling.

The whole is glamorous, soapy, serious fun. We follow the bromance of Joe and Steve across the European Grand Prix circuit, starting and ending in Monaco. Joe is a hot shot champion, a cocksure, womanizing cad, but increasingly aware of the consequences of his actions. Steve is one of those consequences; Joe had a dalliance with Steve’s wife and humiliated her in public. A racer turned novelist, Steve’s going to get his revenge by writing a book about Joe that will humiliate him. But the plot takes a twist as the two become confidants then teammates.

Bonus points to Campbell for refusing the hackneyed ‘driver facing death’ trope that’s ubiquitous in racing movies and a lazy way to inject existential intensity into the proceedings. The existential intensity in ‘The Young Racers’ doesn’t come from the racing, but from the relationships among the characters: Joe and his wife, Joe and his brother, Joe and Steve. And unlike, say, ‘Bobby Deerfield,’ those relationships are never absent from the action on the track.

Jump (1971)

On the face of it, ‘Jump’ (aka ‘Fury on Wheels’) is just another macho-centric, semi-existentialist, exploitation dirt-and-drivers flick.

Tom Ligon plays Chester Jump, son of a Southern dirt farmer, owner of a 1964 Chevrolet Impala, and possessed of a drive to be the fastest racer on the stock-car circuit. “You don’t understand me,” he tells one of his girlfriends. “I got something going. I’m made to drive for a living. I’m gonna do something about it, too!”

Quentin Tarantino describes ‘Jump” as “hilarious and very satirical.” It’s definitely the former, at least sometimes, with top marks going to Lada Edmund Jr. as Enid, Jump’s big-haired, hard-drinking, long-legged lover, and Logan Ramsey, who chews his way through all scenery in sight as the sleazy owner of the garage that serves as the setting for the third act. But except for Ramsey, Joseph Manduke doesn’t let his actors sit in the stereotypes–at least not for long. Jump may be egotistical and hedonistic, but he works hard and his blue eyes see through every con job. This all too earnest and heartfelt to be satire.

When it comes right down to it, Jump’s an idealist. It runs in the family. His sister Mercy is single-mindedly dedicated to Jesus. She doesn’t work, she doesn’t help her mother or father on the farm. She reads the Bible 24/7. She’s the spiritual to Jump’s mechanical.

But they both live in a world that is transactional top to bottom. There’s not a character who doesn’t harass Jump about money, whether its his father chiding him for leaving the barn light on, his mother begging for a handout, his girlfriend asking for rent money, his other girlfriend berating him for chasing away customers before they pay, or the bombastic owner of the garage that convinces him to work for car parts. Jump buys in only as long as he has to–and walks away when the deal gets complicated by personal connections or long-term debt.

The last shot we see is Jump walking through the smoking remains of a demolition derby, away from his battered red-white-and-blue Chevy. He’s refused the big time and the big money in favor of the smash and grab.

The Wild Racers (1968)

“I’m Jo Jo Quillico, king of the hillico. And they call me Jo Jo cuz I got the mojo.”

It’s useful to contrast ‘The Wild Racers’ with ‘The Young Racers,’ another American International Pictures/Roger Corman production released three years earlier. Both are about the world of Grand Prix racing. Both explore the tension between the romantic and athletic lives of their protagonists. Both have a distinctly existentialist vibe. And both feature thrilling footage of the European Grand Prix tour. But they differ fundamentally in the way they treat what they share.

‘The Young Racers’ is melodrama, ‘The Wild Racers’ something more akin to the French New Wave. Rather than dramatic movement toward emotional climax, WR explores a tone and a question: “Jo Jo who?” Played winningly by Fabian, the answer is, “I’m Jo Jo Quillico, king of the hillico. And they call me Jo Jo cuz I got the mojo.” But the real answer is, “Just another good-looking racecar driver.”

‘The Young Racers’ is an existentialist film in the glamorous Sartre/Camus/Beauvoir vein–great clothes, great cars, lots of cigarettes, all in chiaroscuro. The point of reference in WR is Hemingway, captured most vividly in the scene where Jo Jo and Katherine attend a bullfight. “You don’t understand the spiritual angle of the bullfight,” he tells her. This isn’t a film about family, self-reflection, and honesty (that’s YR’s thing), but about one man’s quest for tough-guy independence.

And unlike the racing in ‘The Young Racers,’ here the racing isn’t an expression of character or conflict, but a spectacle of a piece with the beautiful people, glamorous locations, clothing, food, wine, and music. Which isn’t to say that it fails to be a perfect expression of Jo Jo’s character and conflict. Jo Jo is a sexy cypher. Like the protagonist of ‘Downhill Racer,’ he’s a man without qualities, beautiful and fast and not much else

What sets ‘The Wild Racers’ apart is Verna Fields’ editing and Phil Thomas’s sound design. There’s hardly a shot in the film that lasts as long as ten seconds, and most are far shorter. This is a racing film that races. We often hear sound and dialogue from a scene that occurs chronologically later than the scene we’re watching, an example of proleptic sound. Or different scenes are intertwined, their dialogue combined to emphasize a theme, an example of convergent sounds. It’s a remarkable cinematic achievement, perfectly communicating Jo Jo’s inability to ever live in and appreciate the moment or the people he’s with. He’s always trying to get ahead of us.

Thunder in Carolina (1960)

“Look, Stoogie, you just don’t eat peanuts in the pits!”

This is one of a half dozen car-racing movies that were tagged by Quentin Tarantino in a 2013 interview as among his faves. It stars Rory Calhoun as Mitch Cooper, a down-on-his-luck stock car racer who teaches a young mechanic how to drive while hitting on that same mechanic’s wife and smoking an astonishing number of cigarettes.

These early 1960s movies often struggle to portray the motivation to race as something bigger and more meaningful than personal kink. To its credit, ‘Thunder in Carolina’ doesn’t waste much time working out those details, anchoring Les’s growth as a racer to a growing rivalry, though he seems mostly oblivious to what’s happening between Mitch and his wife.

But then the scene shifts to Darlington, South Carolina, and the Southern 500. A panning shot at the pre-race party lands on a massive confederate flag. And the pre-race parade features a Marine Corps band playing “Dixie,” a funnycar surrounded by gamboling clowns in blackface, and dolled-up white girls on a float festooned with rebel flags. And the final shot of the movie shows Mitch and his buddy Buddy (played by Alan Hale Jr. aka The Skipper!) driving down the road to the triumphant strains of, you guessed it, “Dixie.”

Wait. Has this been about rebels and lost causes the whole time?

Probably not. This is a bad movie in so many ways: acting, editing, script, and cinematography are barely competent (director Paul Helmick was a much stronger Assistant Director). I’d characterize the rebel yell stuff as an ideology of convenience. It has its moments, for sure. The racing footage is workmanlike, particularly the opening race with the camera slung low, cars racing past, kicking up dirt and dust. There’s a lovely sequence in the South Carolina hills when Mitch gives Les his first racing lessons. And top marks for the scene where Mitch slaps a bag of peanuts out of the hand of one of his mechanics. Poor Stoogie . . .

Seven Second Love Affair (1965)

The car-racing movies of the 1960s and 70s are a medley of straight, macho masculinity. But with few exceptions (i.e., The Young Racers [1963], The Wild Racers [1968], and Winning [1969]), they don’t offer any kind of critical perspective on either. By and large, they are movies about straight macho men doing straight macho things, most of which involve straight women and greasy, noisy machines.

That’s the case with this short, vivid, very cool documentary, one of the early works of writer/director Robert Abel and cinematographer Les Blank. It tells the story of a few weeks on the California drag-racing circuit, focusing on x-ray technician by day, fuel-dragster driver by night and weekends, Rick Stewart.

As with every other car-racing movie, I watch this with a keen sense of not watching it where it was intended to be watched. Sometimes it’s pure noise and visual spectacle; sometimes it’s quiet and sensitive. One of the best moments of the latter is when Rick tells the story of his first crash while wife Ruby watches patiently (she’s heard this story before), then describes urging Rick to get right back in the saddle. One of the best of the former is the breathtaking crash that draws the movie to its conclusion and hastened Rick’s retirement.

There are two ways this movie strays from the conventional romantic existentialist tough-guy mold of other race-car movies. First, Rick’s family is always on the scene and that scene is generally the garage of their house, a house they couldn’t have afforded without their persistence on the circuit. While the obvious story Abel tells is about drag racing, the less-obvious story is about a (white) middle-class family, part of a rising generation of white-collar workers.

Which is the other interesting thing Abel does that diverges from almost all other car-racing movies. This is the story of entrepeneurs and innovators, staying up all night in their garages tinkering and talking shop. Rick and his crew, including their children (all boys) are the internal-cumbustion-engine version of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. These are nerds making stuff they love, single-mindedly sinking time, sweat, and cash into making a machine that expresses perfection.

Roadracers (1959)

There are three things a great car-racing movie needs to do to be great. The driving needs to be vivid and visceral, the driving needs to matter to the story, and the driving needs to express the evolving dramatic conflict.

‘Roadracers’ does all of this, but with a script that feels like it might be a parody of Freud. Rebuffed again by his father, Rob tells his mother, “I’m gonna smash him the way he smashed me. And it’s gonna be where it hurts him the most [long dramatic pause] on the track.” Cut to mother, looking at first proud then disdainful: “Well, don’t expect me to watch it. I never want to see you in a car again!”

It’s barely an hour and a quarter long, but director Arthur Swerdloff still finds time for Marian Collier to sing a romantic ballad in the local hot rod lounge. The script is bad, the cinematography is clumsy, and the acting relentlessly weird.

But the racing action is outstanding. The movie switches between melodrama at the hot rod lounge and high-octane action at the Riverside International Motor Raceway (a legendary track that is now a shopping mall). The serpentine desert track provides DP Carl Guthrie all the angles he could possibly want. Rear projection is used prudently and done really well (I was fooled for a while). The camera continually changes view to capture the action, sometimes encompassing a landscape with cars twisting and turning across it, sometimes going mobile, most memorably in a shot that swoops low, crossing at bumper-level from driver to passenger side just in time to capture a rival closing with a roar.

And the racing action is dramatic. Because it all takes place on the same track, I grew familiar with it, so the racing felt moored to a stable reality. And because of all of the Freudian sturm und drang, each race matters.

‘Drive to Survive,’ but produced by Ed Wood.

Pit Stop (1969)

Imagine if David Lynch directed a total bad-ass car-racing movie.

Jack Hill’s ‘Pit Stop’ (aka ‘The Winner’) tells the story of Rick Bowman, an amoral drifter who finds himself drawn into a Faustian bargain with wealthy race team owner Grant Willard and the deadly world of Figure 8 stockcar racing. It’s a two-hander, the antagonist one Hawk Sidney, the nihilistic, shit-talking, hard-dancing star of Willard’s team, played by a soulful Sid Haig.

The chemistry between (Jake Cahill lookalike) Dick Davalos and Haig is profound. Davalos is stoic, square-jawed; Haig incendiary. Look for the scene where Hawk apologizes to Rick for a wrecking his Ford Fairlane and thrashing him into the ER: it’s a master class in masculinity, Hawk struggling to find words not because he can’t tap into the emotion, but because he knows that a single wrong step will crash the moment into macho bullshit. This is when Hawk becomes the moral center of the film–Haig’s giant eyes following Rick’s every step towards damnation.

As good as the story is, the production’s better. Hill and cinematographer Austin McKinney nail the punk-rock, destruction alley kink of the Figure 8. McKinney’s black and white photography casts everything in greasy lusciousness, his camera dwelling as lovingly on levers, dented fenders, and whirring belts as it does his actors. One of those–Ellen Burstyn in an early non-TV role–is introduced in a sequence that is as Lynchian as anything David Lynch has ever done–a weird, unsettling, badass, sexy, cybernetic moment of machine-modification and desire.

I’m fascinated by how storytellers adapt the particular mechanics of games and sports to storytelling. Here, it’s the Figure 8 track, a Dante-esque setting if there ever was one, the damned roaring around and around. It’s also a metaphor for Rick’s narcissism.

There’s a moment in the film when the claustrophobic violence of the Figure 8 is left behind, the scene shifting to white sand dunes, d cloud-scudded skies, and dune buggies hauling ass in all directions. It’s a bold, breathtaking moment–a respite from Rick’s journey to the depths.

Not just a brilliant racing movie, but a brilliant movie full stop.

The Love Bug (1968)

“We all prisoners, chickie-baby. We all locked in.”

Full disclosure: I was raised on a diet of live-action, B-grade Disney movies. I liked them all. I forgot how likeable ‘The Love Bug’ is. It’s a truly goofy movie with Disney stalwarts Buddy Hackett, David Tomlinson, and Joe Flynn (who’s great in Kurt Russell nerd adventures like ‘The Barefoot Executive’).

Don’t know the story? A sentient Volkswagen with superautomotive powers befriends some humans, two of them friends, two falling in love. Lots of physical comedy. Bubbly, colorful, looks like everyone’s having fun.

Hackett’s character Tennessee Steinmetz is a fascinating concoction. He’s a Pacific Rim persona. Though he hails from New York, he attained enlightenment in Tibet. “I discovered my real self,” he tells his buddy, down-on-his-luck Jim Douglas. He speaks Cantonese, enabling him to earn the trust of a wealthy Chinese-American, played by Benson Fong.

He’s also an artist. One of the sets is dominated by his workshop, which, in turn, is dominated by a sculpture he’s built out of the parts of a deconstructed Studebaker. His mechanical knowledge and spiritual enlightenment have made him attentive to the implications of technology. Early in the movie, Tennessee warns Jim about the dangers of sentient technology: “We take machines and stuff ’em with information until they’re smarter than we are.” Which is the lesson Jim ultimately learns: he’s a lousy racer–his success is all due to Herbie, who duly whisks Jim and Carole to their honeymoon.

The Love Bug: Rise of the Machines.

Another thing I love about ‘The Love Bug’ is its adaptation of the physics and routes of car racing. There are more than a few car-racing movies which show or reference boys (and only boys) playing with toy cars (my favorite is the opening credits of Roger Corman’s ‘The Young Racers’). The movie does to Herbie what kids do with cars: roll them, crash them, smash them, throw them, anthropomorphize them, make the boy and girl love each other with them. This is a perfectly childish representation of automotive fantasy

It’s also a low-key great San Francisco movie with a hilarious easter-egg in the middle. Producer Bill Walsh made Herbie’s number 53, the same number as Los Angeles Dodgers great Don Drysdale. Burn.

Eat My Dust (1976)

“I’m not going with Hoover, he’s just taking me for a little ride!”

As much a classical farce as it is a racing movie, ‘Eat My Dust!’ is also, at times, a deeply romantic, even lyrical film.

Directed by Charles B. Griffith (writer of classic Roger Corman flicks like ‘The Wild Angels,’ ‘Little Shop of Horrors,’ and ‘Death Race 2000’), it tells the tale of the rebellious son of a rural California sheriff desperate to impress a girl with his rebelliousness and driving skills.

It’s silly, silly stuff, stuffed with the bizarre situations, character types, and slapstick violence we want from classical farce, but without a whiff of cruelty towards anyone involved. There’s real affection for the characters and the actors, even those who are no more than types. This is especially notable when it comes to Darlene, the girl Hoover wants to impress but who, ultimately, is just there for the ride. “It wasn’t me at all, was it?” he asks as she walks away into the Halloween night. Darlene has been in charge the whole time–and she knows it.

That final note of melancholy echoes the several deeply romantic, almost pastoral sequences in the film, my favorite being when Hoover and Darlene run out of gas and have to push their car to an abandoned farm. Eric Saarinen’s photography and David Grisman’s (yes, that David Grisman) score shift the movie out of high gear into something innocent and lovely.

There’s something soulful here that I didn’t expect, something that puts ‘Eat My Dust!’ up there with some of the best racing movies. Soufulness without self-seriousness–like some of the best farces.

N.B. The posters for ‘Eat My Dust!’ show Ron Howard wearing a cap with the confederate flag. In the movie, he doesn’t.