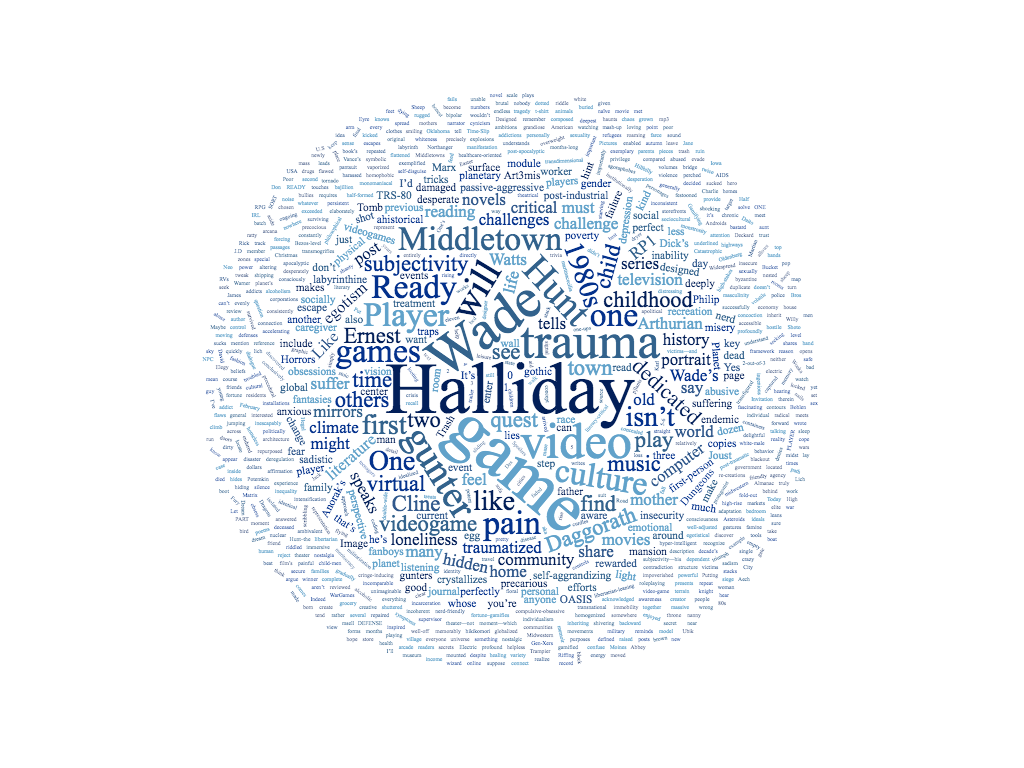

This is the third in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

(Spoilers)

In my previous post, I reviewed some of Ready Player One’s (RP1) many flaws: its cringe-inducing treatment of race, gender, and sexuality; its incoherent vision of online community; its ahistorical and politically homogenized sound track; and the way it leans in to libertarian beliefs about the nanny state, meritocracy, and rugged individualism. But, most importantly, I underlined how important it is that we not confuse Ernest Cline, the book’s author, with Wade Watts, its narrator.

(Not Wade Watts)

(Not Ernest Cline)

In this post, I will argue that RP1, as flawed and inconsistent as it is, presents a more consciously critical view of video games, nerd culture, and virtual community than readers have generally acknowledged. The key to my reading is the concept of trauma.

Gamifying trauma

Riffing on the work of his philosophical hero Hegel, Karl Marx wrote that the events of history tend to appear twice, first as tragedy, then as farce. Ernest Cline one-ups Marx: In Ready Player One, the events and personages of history repeat once more, as a video game.

Halliday’s Hunt–the Easter egg quest whose winner will inherit an unimaginable fortune–gamifies the 1980s. It transmogrifies the decade’s video and roleplaying games, music, television, and movies into a nerd-friendly high-stakes Arthurian quest. But the Hunt makes no mention of the “other 1980s,” the 1980s of AIDS, accelerating climate change, rising income inequality, the radical deregulation of global markets, the militarization of the police, the rise of transnational corporations, the intensification of the war on drugs, or mass incarceration.

In case you didn’t hear, the 80s sucked.

But this isn’t to say Halliday isn’t aware of all that. He writes about it constantly in his journal, known to gunters as Anorak’s Almanac. And this isn’t to say that the gunters aren’t aware of it, either. How could they not be? It’s all around them.

It’s the structure of that awareness that I find fascinating. In its labyrinthine, self-aggrandizing sadism, Halliday’s Hunt mirrors the anxious, passive-aggressive subjectivity of a hyper-intelligent, socially anxious, sexually insecure, libertarian-leaning, creative, precocious, ingenious white-male nerd who finally gets the chance to give it to the jocks. But it also mirrors the subjectivity of a helpless child suffering unending emotional abuse at the hands of his mother and father, a child with nowhere to run and nobody to help him, desperately seeking escape and affirmation in games and coding. Halliday’s Hunt mirrors the precarious subjectivity of a Midwestern boy with abusive parents and dwindling opportunities living in a town sliding into post-industrial ruin.

To play Halliday’s game, the gunter must play Halliday’s trauma.

What do I mean by “trauma”? Put simply, trauma is an event that is profoundly, inescapably painful, shocking, and distressing. It comes in many forms: a child abused by their caregiver, a community surviving a months-long military siege, a town flattened by a tornado, a worker harassed by a supervisor. But trauma isn’t defined by what it is so much as by what it does to its victims—and what its victims do. Indeed, two people might suffer the same experience, but only one of them be “traumatized” by it. The traumatized suffer not only from the event directly but also from the failure of the emotional, symbolic, physical, social, and cultural tools they have to make sense of their suffering, to cope with the pain, to find a path to healing. And that failure leads to a variety of post-traumatic symptoms. For the individual, this might include loss of trust in others, the inability to sleep, or compulsive-obsessive behavior. For communities, this might include endemic alcoholism, chronic depression, and poor physical health. (The literature on trauma is massive. For a literary-critical approach, see this. For a more accessible, healthcare-oriented perspective, see this.)

Do fanboys dream of electric sheep?

If anyone understands fear and desperation, it’s Wade Watts. When we meet him, he’s hiding, shivering and starving, behind a clothes dryer in the double-wide he shares with a dozen others, perched near the top of an Oklahoma City “stack,” a high-rise shanty town of trailer homes, RVs, and repurposed shipping containers. “I was the only child of two teenagers,” he tells us, “both refugees who met in the stacks where I’d grown up. I don’t remember my father. When I was just a few months old, he was shot dead while looting a grocery store during a power blackout” (15).

(From Ready Player One, Warner Bros. Pictures)

Wade was raised by his mother, an OASIS sex worker, who, despite her efforts to block out the noise, could not keep him from hearing her “talking dirty to tricks in other time zones” (15). A loving, dedicated caregiver, she was also an addict. When Wade was eleven, “she shot a bad batch of something into her arm and died on our ratty fold-out sofa bed while listening to music on an old mp3 player I’d repaired and given to her the previous Christmas” (19). He then moved in with an abusive aunt, who treats him less as a family member than a sure source of government aid. Poor and overweight, he is a target of bullies.

The pain of Wade’s personal trauma is exceeded only by the apocalyptic trauma all around him: “the ongoing energy crisis. Catastrophic climate change. Widespread famine, poverty, and disease. Half a dozen wars,” cities vaporized by nuclear explosions, “[p]lants and animals . . . dying off in record numbers” (1, 17). Like so many others, Wade has no hope, no ideals, no agency: “Maybe it isn’t a good idea to tell a newly arrived human being that he’s been born into a world of chaos, pain, and poverty just in time to watch everything to fall to pieces. I discovered all of that gradually over several years, and it still made me feel like jumping off a bridge” (18).

Like Halliday, Wade escapes his misery by playing games, watching television, listening to music, scribbling page after page in his journal. And like Halliday, his obsessions make him feel special, chosen, elite. And aside from the relatively well-adjusted and well-off Art3mis, the other “High 5” are in the same boat. Aech is homeless, kicked out by her homophobic mother, roaming the Fury Road highways of the post-apocalyptic U.S., unable to share her IRL identity with her best friend. Shoto and Daito are hikikomori, agoraphobes who do not leave their rooms, dependent on their families and friends to feed them, socially isolated.

In his 2011 review in USA Today, Don Oldenburg compared RP1 to “Willy Wonka meets The Matrix.” But in light of how damaged Wade is, in light of his cynicism, his loneliness, his addictions, his desperate efforts to connect with others, and his inability to understand why they reject him, he reminds me less of Charlie Bucket or Neo than the damaged child-men in Philip K. Dick’s novels: Jack Bohlen in Martian Time-Slip, Rick Deckard in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

You can’t go home again and again and again and again and again . . .

In Anorak’s Invitation, Halliday tells the world, “I suppose you could say that [the egg is] locked inside a safe that is buried in a secret room that lies hidden at the center of a maze located somewhere . . . up here” (5-6). That pretty much nails it. The Hunt is a kind of procedural manifestation of Halliday’s troubled subjectivity—his elaborately designed defenses against the pain of his childhood and the global disaster of 2044 provide the architecture of the Hunt.

The Hunt is composed of three challenges. The first to solve all three will be rewarded with Halliday’s Bezos-level fortune and control of the OASIS. Each challenge is a byzantine mash-up of video game and RPG arcana, 1980s pop culture trivia, and Halliday’s obsessions.

For example, the first challenge requires the gunter to locate a virtual recreation of the Dungeons & Dragons module Tomb of Horrors (1978), evade its traps and tricks, and enter the throne room at its center. There, they find a powerful wizard who challenges the gunter to a 2-out-of-3 game of Joust (1982), an arcade game in which the player controls a knight mounted on a flying bird. If they beat the Lich, the gunter is rewarded with a key and yet another riddle: “What you seek lies hidden in the trash on the deepest level of Daggorath” (84). The dedicated gunter will quickly recognize this as a reference to an old computer model (the TRS-80 aka the “Trash 80”) and computer game (Dungeons of Daggorath [1982]). The truly dedicated gunter will recall that the TRS-80 was Halliday’s first computer, and Daggorath the game that inspired him to become a designer (85). Putting two and two together, they realize they must travel to the planet Middletown, where they will find a virtual recreation of Halliday’s childhood home, which they enter, walk to Halliday’s bedroom, boot up the Trash 80 therein, and successfully complete Daggorath. At that point, a transdimensional gate opens in the wall . . .

. . . through which they climb and discover the final challenge: A first-person video-game adaptation of the movie WarGames (1983), in which the gunter must precisely duplicate the dialogue, gestures, and movements of the film’s protagonist from first-person perspective.

Yes, Art3mis, “Halliday was one crazy, sadistic bastard” (308).

Do you see the potent contradiction here? The Hunt allows Halliday to share his fear, pain, and loneliness to anyone interested in inheriting a bajillion dollars. But that grandiose egotism (what is more egotistical than altering the world economy by forcing everyone to play your game?) is, at the same time, deeply hostile. Halliday hides his pain in a labyrinth festooned with brutal traps that can be survived only by those who suffer and obsess like he did.

Halliday will share his life with you, but only if you’re as good at games, music, and movies as he is. And if you take one wrong step, you’re dead.

(Who wouldn’t want to play Joust with this guy? Image of the lich from the original Tomb of Horrors module, by the incomparable David A. Trampier)

That volatile concoction of self-aggrandizing egotism and sadistic self-disguise is exemplified by planet Middletown. Designed personally by Halliday, its surface is dotted by “256 identical copies” of his childhood town, “spread out evenly across the planet’s surface” (101). Each of the copies is an idealized representation of 1980s midwestern life, its residents friendly, its sky clear, time moving neither forward nor backward on an endless autumn day.

But in the midst of each of those 256 Middletowns is an empty house, Halliday’s childhood home. “For whatever reason,” Wade tells us, “Halliday had decided not to place NPC re-creations of himself or his deceased parents here” (103). Yes, there is a portrait on the wall of the Halliday family, a portrait that doesn’t “hint that the stoic man in the brown leisure suit was an abusive alcoholic, that the smiling woman in the floral pantsuit was bipolar, or that the young man in the faded Asteroids t-shirt would one day create an entirely new universe” (103). But of course, the portrait does hint at all that. Wade knows what Halliday endured. That silence, repeated 256 times, speaks volumes.

In its planetary scale and monomaniacal attention to detail, Planet Middletown crystallizes the loneliness, immobility, and passive-aggressive egotism that enabled James Halliday to turn misery into triumph. The nested, labyrinthine challenges map the contours of a desperate escape transfigured into an Arthurian quest. But it is an Arthurian quest set in a gothic mansion.

Planet Middletown is nostalgic, perfect, and, like a gothic mansion out of Jane Eyre or Northanger Abbey, riddled with secrets, concealed doors, hidden passages. Halliday’s Middletown is a planetary Potemkin village, a gamified memory that denies the shuttered storefronts, the impoverished single mothers, the addicts, and the endemic depression and violence of the American post-industrial terrain captured so memorably in Hillbilly Elegy, J.D. Vance’s memoir of life in Middletown.

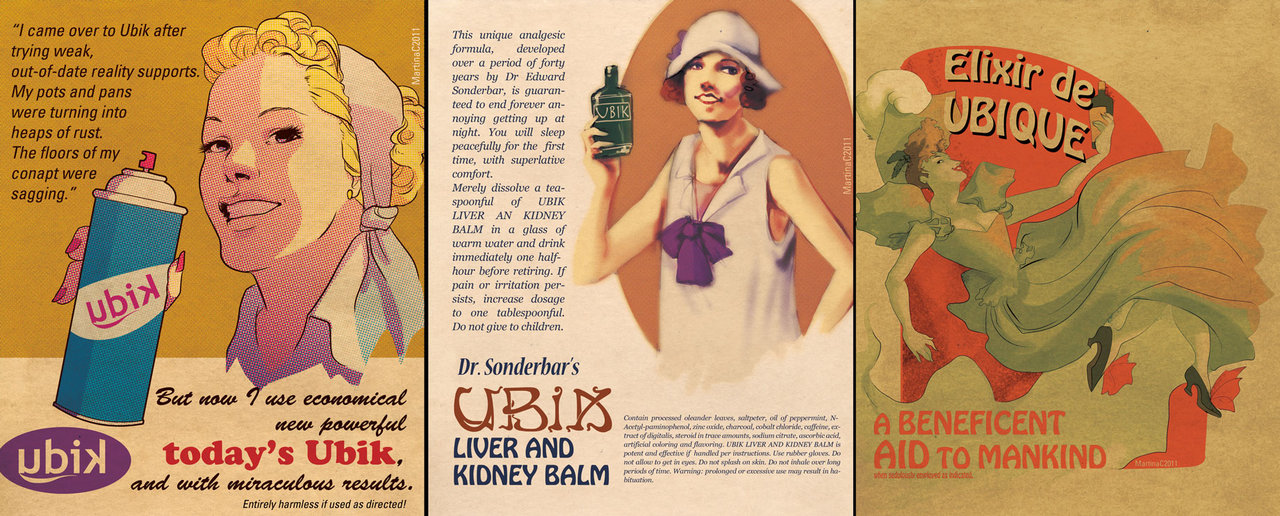

Like the Des Moines, Iowa, of Philip Dick’s Ubik, the nostalgia curdles the moment one touches it.

(Image by martinacecilia)

Ready Player One is the perfect video game novel of our moment—which is why it kind of sucks

Let me be perfectly honest: I feel deeply ambivalent about Ready Player One. On one hand, it crystallizes a history of video games, video game players, and video game culture that speaks not only to the privilege enjoyed by straight, white, institutionally secure men and the children who want to be like them. It speaks to the profound personal and social insecurity that haunts their every step.

On the other, it fails to consistently signal the connection between that insecurity and its treatment of gender and race and its naïve, ahistorical, apolitical vision of virtual reality and globalized game culture. And it is perfectly designed to tweak the fantasies of fanboys and Gen-Xers. I’ve read it before and I’ll read it again. I’ll see the movie several times. I’m a sucker for its charms.

So at whose feet do we lay this delightful monstrosity? Are we reading Wade’s traumatized subjectivity, his precarious masculinity, his whiteness? Or are we reading the ambitions, fantasies, and half-formed critical consciousness of Wade’s creator, Ernest Cline?

I don’t think that’s a question that can be conclusively answered. And that’s what makes Ready Player One an exemplary text of our current video game culture and our current sociocultural climate.