October 24, 2023

This is the twentieth in a series of posts dedicated to works of playful literature and theater—not just games that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another games, game players, and game culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, though one that’s more focused on videogames rather than games more generally, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

I’ve recently purchased My Best Game, an itch.io bundle of 52 (!) indie tabletop roleplaying games with one feature in common: their designers considered it their best game. The games in the bundle vary widely in terms of narrative genre, game mechanics, and professional polish. But all of them are interesting, fun, and heartfelt! I suspect that the bundle provides a useful perspective on the current state of the indie TTRPG scene.

Perhaps foolishly, I’m committing myself to writing brief (well, brief-ish), descriptive reviews of each of the 52 games in the bundle. These reviews are based only on my reading of those rules, so don’t reflect any of the discoveries that come through play. Since the bundle is no longer available, I’ve provided links to each of the game’s itch.io pages.

Perhaps even more foolishly, I’m adding to this list the indie games I’m purchasing through other sources, whether itch.io, DriveThruRPG.com, and my favorite game store, Games Unlimited, in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh. I’ll make sure to indicate purchase options for those, too.

Note: I’ve done my best to discover the preferred pronouns of the designers. When that proved impossible, I’ve defaulted to they and their.

Note: I’ve done my best to discover the preferred pronouns of the designers. When that proved impossible, I’ve defaulted to they and their.

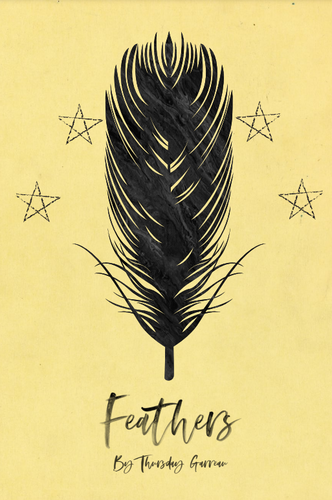

Feathers

a slice-of-life game of fallen angels and Belonging Outside Belonging

by Thursday Garreau

Thursday Garreau describes Feathers as “a game of angels, fallen into our world, wandering in unfamiliar, fragile bodies, looking for a people, places, and selves they can find comfort in.” It’s a game best described as delicate, intimate, perhaps even cozy.

Though based in Avery Alder’s Belonging Outside of Belonging engine, it eschews a few elements of Alder’s system. Instead of the six Character Roles Alder recommends, Garreau goes with three: The Lover, The Dancer, The Dreamer. So, while this provides the minimal “triangulation” for “community drama” to thrive (as Alder puts it in her maker’s guide in Dream Askew/Dream Apart), it also constrains play to a small group and, thus, a more intimate kind of storytelling. Similarly, Garreau goes with four Setting Elements (called “Situations” here) instead of six, softening the strong relationship between setting and character that is one of the hallmarks of the BoB system. Finally, while they keep the BOB mechanic of Strong, Regular, and Weak Moves, Garreau has done away with Lures and the broader ludonarrative principle of “making trouble” for each other.

These choices speak to the way Garreau envisions Alder’s idea of “a marginalized group of people living together in a precarious community.” Alder’s Dream Askew (“Queer strife amid the collapse”) or Benjamin Rosenbaum’s Dream Apart (“Jewish fantasy of the shtetl”) are designed at least partly with those who do not identify as queer or Jewish in mind. A section on “Asking and Correcting” advises players to “ask questions” if they don’t get something and “gentle corrections” when someone gets something wrong either factually or tonally.

That’s not the case here. This is a game by a queer-identified designer for queer-identified players. It voices its design in the singular and collective first-person: “This story, just like ours, is ultimately an optimistic one,” “We’re not alone, for better or worse.” The precarity of this community is situated less in terms of the broader situation than in the bodies and voices of its player-characters, angels who dream of wholeness and community. This is a game whose empathy structures are oriented not towards outsiders (i.e., those who don’t identify as queer) but towards the three who gather to play. It’s not exclusionary, but it also doesn’t make any welcoming gestures towards the cis or straight. In that respect, Feathers is a game that affirms the significance and precarity of queer play and the need to empathize with each other. (10/2/23)

Candied Violets

The Sweet Treat RPG

By Monroe Soto

Candied Violets is a micro-RPG that packs a whole lot of flavor into its few pages—imagine The Great British Bake Off but adorable woodland creatures.

The ludonarrative is, as is usually the case with micro-RPGs, simple in terms of structure, mechanics, and drama. Similar to The Great British Bake Off, there are three challenges, each more challenging than the last, each assessed by a panel of judges. Dramatic friction is generated, first, by the contest structure: the players play the ambitious woodland pâtissiers, each with a favorite ingredient and special skill; the GM plays the judges who, in addition to being woodland fauna, have allergies and preferences that the contestants may or may not be aware of. The GM, in the guise of the judges, sets the overall theme for each of the three rounds, each round requiring a Sniffer, Tastebuds, and Timing check, with Forage and Cutes (when attempting to charm or win sympathy with those big Disneyfied eyes) sprinkled in to spice up the proceedings. Everything is determined by the role of two six-sided die, low roles resulting in a disadvantage, high roles the opposite.

The other source of dramatic fun is the openness of the ludonarrative, another one of the characteristics of the micro-RPG genre. Generality of description promotes creative improvisation in terms of both storytelling and interpretation of die roles. Add that to the dramatic tropes of the reality-television show and the reliance on ritualized judgment, one sees how Candied Violets promotes all kinds of friendly banter, both in-character and out. A reviewer on itch.io complimented the game for its “great balance between cute and chaos” and I think that captures it. (10/4/23)

Like SKYSCRAPERS*

*blotting out the sun

Speak the Sky

The designer of this collaborative “2-player writing game of: excessive footnotes, killing the author, and woes in translation” claims* not to have read Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire until after he had designed the first version of the game.† This strikes me as rather ludicrous, but, as the designer wisely notes, “This doesn’t matter much.”‡

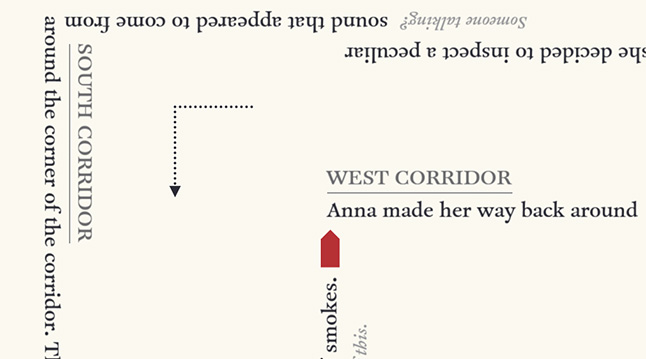

The game posits one player as a Writer, the other as a Translator, the former an exile writing their magnum opus in a foreign land, the latter supporting them “out of pity and admiration,” but also elbowing their way into the text by way of a series of footnotes that, while intended to clarify the Writer’s text, inevitably digress into the idiosyncratic, narcissistic, or neurotic. The two players are advised to sit at a table across from each other, each taking a turn to write. The Writer starts a page by writing a chapter title, then writing one to six lines of text. The Translator then chooses one to six lines in that text to footnote. Once a page is filled, the Translator sums up the rest of the imaginary chapter and play continues to the “Between pages” phase in which an event happens that affect the fictional pair in some fashion.

Like Pale Fire, what emerges is a hybrid text that tells one story on its surface, another between the lines, and yet another around those lines. It reminds me of Surrealist writing games like Echo Poems, Translation Poems, or Parallel Stories, games in which players transform each other’s words by seizing upon a fragment or a sudden association or inspiration that may have little relationship to the intention of the other player but can produce marvelous results by way of the variability of the non sequitur. Here, the productive disjuncture of text and paratext is fueled by a set of random prompts that are correlated with a standard 52-card deck: Seeds that designate subject matter for the Writer, Footnotes for the Translator, and Events or Figures for the Between pages phase.

The game’s penultimate phase directs the two players to assemble the pages into a manuscript into book form, meaning all the little paratextual bibs and bobs of the contemporary book: a brief biography of the writer, a blurb for the cover, a commentary for readers, a letter of proposal to an imagined publisher. The game ends on a perfectly awkward, narcissistic note as the players must “find someone and convince them to read the final story, if you can bear to do so,” including the designer himself, who graciously invites the players to contact him.

This is all perfectly delicious, as far as this fan of self-referential metafiction is concerned. (10/6/23)

* Though this claim is positioned near the end of the text, in an “Anti-bibliography,” a symptom, perhaps, of a certain mendaciousness on the designer’s part or, perhaps, of a willingness to string the reader along, to watch them nod furiously, perhaps even text their two elder children, “holy shit! I just found a ttrpg based on Pale Fire!”

†This being the second version of the game, at least, given the ambiguous “v2.2” beneath the subtitle. Which raises a question concerning the events that separated “v1” from its subsequent iterations.

‡A classic stratagem of the inheritor who, upon being reminded of the value of the inheritance, must admit to their dependence upon those who came before. Matter much to whom?

Weasel Overdrive

Richard Kelly

Kelly describes Weasel Overdrive as a “cyberpunk one-session or short campaign trpg about being strange people in an uncaring metropolis.” More specifically, it’s about weasels and the fixers-for-hire who love them. And I’ll be honest, when I first read this, I thought it was a joke.

Weasel Overdrive is an example of the kind of TTRPG that is 90% “I’ve got this weird idea” and 10% mechanics. Not a bad thing per se, but in this case, that weird idea is anchored in two extremely specific niche ideas: fixers with ghost weasels and cyberpunk. And the mechanics are fuzzy, maybe just not thought through. The designer, Richard Kelly, is clearly aware of this: “I believe in you,” he writes in the conclusion and, elsewhere, that this “is a game you want to get loose and improvise with.” In practice, this means that the game probably won’t be much fun for players who aren’t deeply familiar with the cyberpunk genre and its greasy streets, metacorporations, and grim-noir gig economies. Aside from some flavor text and vivid photos of urban settings with weasels photoshopped in, there’s not much here to help with worldbuilding.

So, how does it work? One player plays the “Weasel-user,” a “member of an ancient bloodline (or else people who have had their own problems solved by the members of that ancient bloodline) who are bonded to half-spirit, half-corporeal weasels.” The other, non-GM players are the “supporting cast.” These characters have various “Trade Skills” that can be bartered and leveraged by the Weasel-user. The GM guides the action forward by way of the Client. Storytelling is handled by everyone at the table

The action begins when the GM presents the Client, their request, and explains the obstacles standing in the way of fulfilling that request. The players all talk it through, the Supporting Cast members identifying when and how their Trade Skills might help with an obstacle, then rolling as many D6s as they have points in that Skill. The Weasel-user modifies those rolls using their Powers at the expense of Curses. After all obstacles are either successfully or unsuccessfully dealt with (and, frankly, I’m kind of baffled by the rules that govern this as they are definitely loose and improvsational), we enter the Unfolding the Consequences phase. In faith to the grittier, nihilistic end of the cyberpunk storytelling spectrum, this is mostly about bad things happening, those things mostly resulting in everyone in a far worse situation than when the story started, dead, or newly be-weaseled. At that point, the GM steps in to do a little conclusive storytelling and play concludes.

Kelly admits that “a lot of this game isn’t contained in the book.” I think most players could use a little more—maybe a list of novels, movies, comics, and videogames? (10/7/23)

Vibe Check

Enter the Inversion

By Josh Hittie

I was thoroughly baffled by this one upon a first reading of its sixty-one vibrantly colored pages. In part, that’s a problem of layout. Vibe Check is a sight to behold thanks to layout artist Rae Nedjadi. The pages are a densely layered riot of color, fonts, artistic styles—layout as wildstyle. In this respect, Nedjadi accomplishes one of the key goals of the TTRPG layout designer—to provide players a vivid sense of a game’s, well, vibe. Vibe Check takes place in the “Inversion,” a surreal, neon-dystopian urban afterworld in which the player-character has seven days to battle the Pandemonium, “dangerous manifestations of the Inversion itself, run amok through the Inversion as tools of the Watchers,” those last being the supernatural cyberpunk gods that rule the game. Nedjadi captures that neon-surreality through a maximalist, at times dizzying design. But that layout falls short on a second, more important goal of the layout artist: legibility.

I beg you, Josh Hittie and Rae Nedjadi, a please provide a printer-friendly, more reader-accessible version that’s less than 132.5 MB!

But I was baffled in another, more enticing way. I couldn’t make sense of how Vibe Check worked. A small paragraph on the credits page indicated the Lumen system created by Spencer Campbell. So, I found and read Campbell’s System Reference Document (https://gilarpgs.itch.io/lumen) and Seamus Conneely’s review of it (https://cannibalhalflinggaming.com/2021/06/18/lumen-review-an-srd-for-the-quick-and-powerful/). As I discovered, the Lumen system is inspired by high-octane shooter-looters like Diablo and Destiny. The rules-light system focuses on super-powered, fast-moving, high-flavored combat. Frankly, I had never imagined that one could emulate in a TTRPG the pace and scale of those games—not just the combat but the drop-mechanics and flow. And then it clicked.

Vibe Check is Destiny meets The Hype.

As Hittie puts it, “What’s the point of fighting for your life if you don’t at least look good doing it?” The player-characters construct their Looks via seven Brands, among them Antiquity’s Glance (“Comfortable and casual without sacrificing style”) and Beautified Grotesque (Elaborate and gothic, finding beauty in the profane). Each Look provides distinct bonuses, with the seventh, Lunar Crash Threads, only available from special stores or dropped as special boss rewards. Fashion is fluid, so Brands ebb and flow according to the random rolls of Trends. Thus, a given session will have one Brand on top, the other on the bottom, bonuses and penalties accordingly. Looks come in five types: head, shirt, pants, shoes, and accessories. Brand loyalty pays off: outfit yourself three or more items of the same Brand and bonuses ensue. Apparel and accessories are dropped in combat—and, true to the looter-shooter vibe, drop early and often—but can also be purchased at Stores between missions. Like Destiny and Fortnite, a big part of Vibe Check’s fun is playing with your player-character’s paper doll, though the player gets a lot more control of the details. Complementing Looks are Tokens, “small physical objects that Players use to activate their powers. They are manifestations of the Player’s powerful souls,” though also opportunities to tap into their storytelling abilities. Tokens come in tiers and Hittie has created dozens of them. Again, this is a game as much about the looting as it is the shooting. And the Tokens provide the spectacle, ranging from atmospheric effects like Revenge of the Carboniferous (which creates a large oil slick) and Sunset (which bathes the battlefield in amber dusk, providing additional damage bonuses) to weapons like Pact Chain (Bind and control non-boss enemies) and Quantum Daggers (a set of neon throwing knives).

But it’s also about the shooting. Less numerous but no less imaginative are Vibe Check’s enemies, which come in three ranks: low-powered Minions like Asphalt Gremlins and Wheelie Mobs; Striker Enemies in the form of Neon Jellies or Traffic Light Cyclopses; and big bosses like Concrete Krakens and Skyline Dragons. True to the Lumen system, combat has been stripped of anything that might lead to “analysis paralysis” or the possibility of a power not working due to a low die roll. When a PC uses a power, it simply works, no die roll needed. As Campbell puts it in his SRD, “Powers are the opportunity to show off,” and it is the GM’s job to respond to the Players’ actions by describing “Big Changes” to the battlefield—alarms suddenly blaring, enemies changing their tactics in a surprising way, the environment shifting unexpectedly, or a new enemy type showing up. Vibe Check gives us combat as runway catwalk—the chic versus the cheugy. (10/24/23)

VOID 1680 AM

A Solo Playlist Building Game

By Ken Lowery

I bought this at Games Unlimited in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh on a stop-off between Independent Brewery and the Manor Theatre. I was first drawn by the evocative cover by Jordan Witt and its subtitle, “A Solo Playlist Building Game.” But I was hooked when I saw its ludonarrative.

The player plays a DJ for an AM radio station, and the game represents a single show comprised of four blocks of three songs each, interspersed with talk. To make this happen, the player divides a standard card deck into suits and face cards. The suits represent the four song blocks, each of them with a different mood. They draw three cards from the first suit to guide the selection of the first three songs, each card keyed to an idea (i.e., “You’re ready to take a walk or go running.” or “A song that got you through a breakup, romantic or platonic.”) and a question (“What song sets the pace for you?” “How does it feel to hear it again?”). Once they’ve selected the songs for that block, they press record on whatever device is handy, introduce the first track in their chosen DJ style, then press play. As the three songs play, the player draws a Caller Card from the face-card deck and then correlate that with the suit of the current block. What emerges is a random mix of persona (“a young Caller on the cusp of adulthood,” “an elder, middle-aged or older,” etc.) and mood (mellow, passionate, melancholy, etc.), that mood further differentiated in terms of subject matter (i.e., romance, friendship, family, etc.). Once the third song of the block concludes, the player then backsells the previous two tracks and talks about the Caller to whatever extent they wish. Rinse and repeat until the fourth block is played and the evening’s show arrives at its conclusion.

Though grounded in the real world of AM radio, it strikes me that VOID 1680 AM is genre-agnostic. One might just as easily assemble one’s playlists and callers in a version close to our own world or in the speculative worlds of, say, Welcome to Night Vale, The Vast of Night, or the apocalyptic eighth episode of Twin Peaks: The Return.

I enjoy solo TTRPGs, but this is one of the few that make intrinsic sense as a solo TTRPG—a game in which the form of solo play supports and is supported by its narrative situation. As Lowery writes, AM radio is “lone voices in the darkness, saying what they cannot contain, seeking connection with like minds. Voices like yours . . . You will speak, but you will never know who hears you. You will bare your soul, but you will never know who—if anyone—is truly listening.” The intensely imaginative isolation of the TTRPG is a perfect ludonarrative analog of the “punk DJ, the outlaw country enthusiast, and the conspiracy theorist alike.” Further, it literalizes the idea of voice by asking the player to record their vocal performance and mix it in with the songs they curate—literalizes it further if they accept Lowery’s invitation to send him their recording so he can broadcast it through his actual AM transmitter in his garage and have it posted on his Void Affiliates YouTube channel.

A clever, thoughtful merging of genre, transmedial storytelling, and performance. (10/24/23)

CARZ

Carnage. Automobile. Radical. Zeta

By Adira Slattery

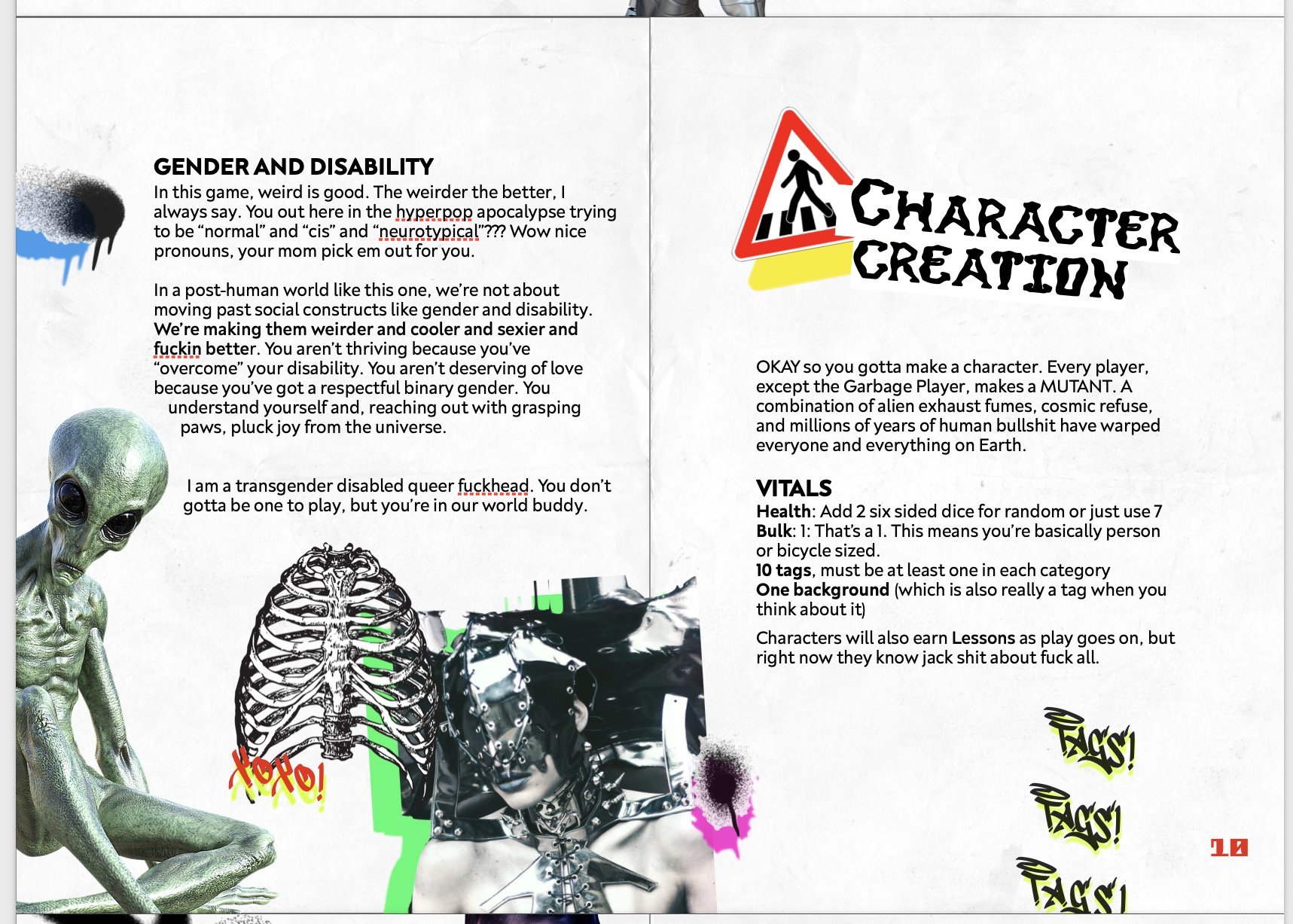

One of the distinguishing features of the indie TTRPG scene is the emphasis placed on writing and layout. Both of these are vital to any rulebook—as with any genre of technical writing, the information in rulebooks must be communicated and organized effectively. Conventionally, clarity and utility are the priority—the rules and mechanics should be explained clearly; that explanation and its relationship to the storyworld should be organized to help players find what they need when they need it. But flavor also matters. Word choice, the arrangement of text and image, font selection, color, and other visual, rhetorical, and organizational elements communicate more than just how the game is played—they communicate the feel of play.

Flavor is especially important in the indie TTRPG scene. MÖRK BORG is exemplary, with its violent color contrasts and constantly shifting layout. No doubt, a more expressive approach is a smart strategy in a crowded marketplace where choices are organized in terms of thumbnails and blurbs or crowded store shelves. MÖRK BORG’s garish yellow cover and lurid illustrations catch the eye and imagination. But it also reflects a rejection of a game-design aesthetic that has long dominated the mainstream market—an aesthetic that privileges order and marginalizes the queer, the divergent, the weird, and the angry. But it’s rare to find a TTRPG rulebook that extends flavor into the writing that explains the rules—we might not find an actual rule in MÖRK BORG until we’re 18 pages in, but that rule and the others are explained in a fashion similar to any other rulebook: orderly, rational, rhetorically neutral.

That’s not the case here.

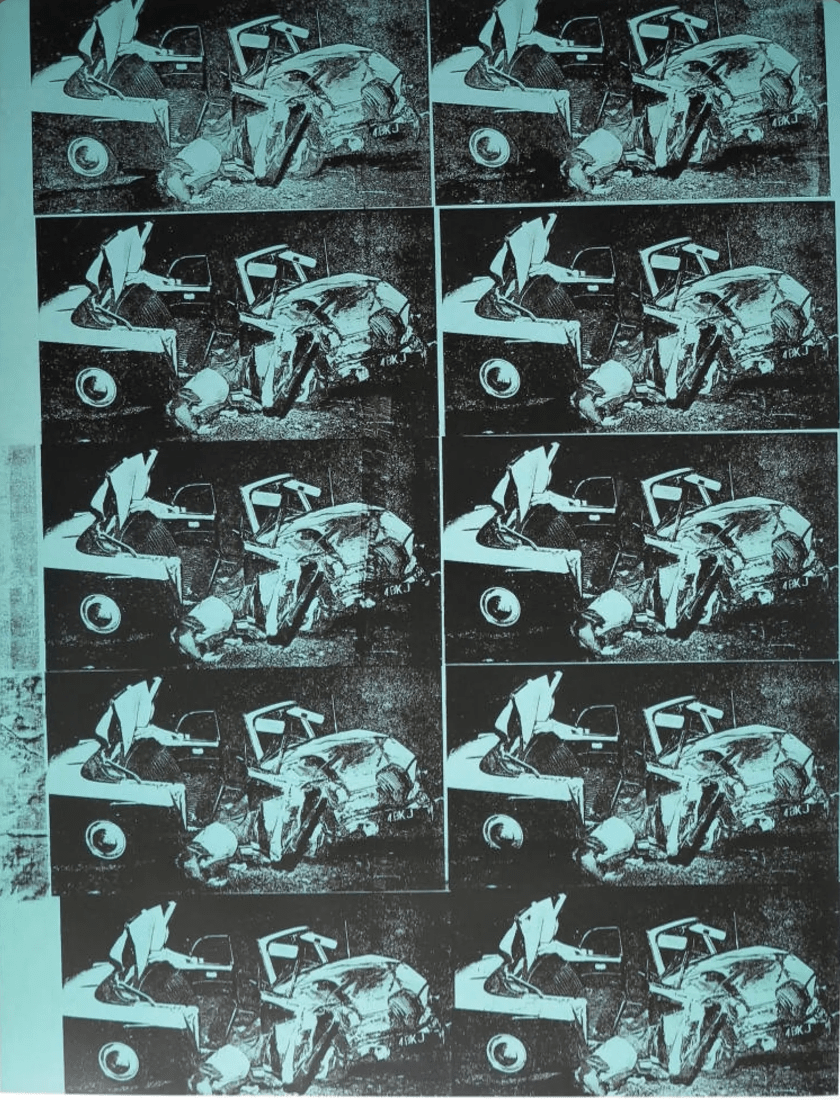

“This is a mother fucking game,” Adira Slattery tells us. Indeed. CARZ is a post-apocalyptic demolition-derby with narrative roots in movies like Death Race 2000 and the Mad Max series and familial resemblance to games like Chad Irby and Steve Jackson’s Car Wars (1980) and Colin Chapman’s Atomic Highway (2010). Like those, CARZ is about high-velocity, over the top, automotive rage-festing.

But where CARZ separates from these and most other TTRPGs is its cover-to-cover embrace of its mother-fucking premise. CARZ isn’t only set in the “hyperpop mutant garbage of this post-apocalypse cosmic dumpster that we call earth” but reads like a game you’d pull out of that dumpster. This is a rules-light, rough-edged, game heavy on attitude in terms of both the world it describes and its trashcore layout, courtesy of Maria Mison (an accomplished game designer in their own right https://mariabumby.itch.io/). But it also reads differently, which I’ll get to shortly.

The player-characters are Mutants from one of ten backgrounds ranging from Lunar to Sheltered to Wacky (“Maybe you’re a living skeleton . . . or a badger who can say swears”). The GM, here called the Garbage Player, handles the usual stuff: voicing NPCS, organizing scenes, and managing the ludonarrative system of Tags. Slattery writes, “Everything is made of tags. Characters have tags, vehicles have tags, places have tags, stuff has tags. Tags tags tags tags tags. Nouns, adjectives, whatever!” Tags are the “quintessence” of the things that are and happen in this world. These tags come in four categories when it comes to defining characters (Carnage, Automobile, Radical, and Zeta = CARZ!) and in several others when it comes to action elements such as vehicles, places, and detours.

The action is governed by a simple dice-rolling mechanic. All actions get at least three six-sided dice, more for each Tag that applies favorably, fewer when they suggest a disadvantage, but never fewer than three. Matches define the degree of success—more matches, more better. But the governing principle is improvisatory, over-the-top, chaos. “When in doubt, blow something up.”

This is all great, flavorful fun, but what sets CARZ apart from most TTRPGs, even the most indie of the indies, is its rejection of the neutral-toned, rationalistic, rules-are-distinct-from-story approach to games writing. In the section, “Reading this mess,” we’re told, “First off, we’re gunna be in this colloquial style the whole time.” That style extends to a note on gender and disability that is more than just a nod to an ethos of accessibility: “I am a transgender disabled queer fuckhead. You don’t gotta be one to play, but you’re in our world buddy.”

Cr*pple Punk as game-design aesthetic? In! (11/5/23)

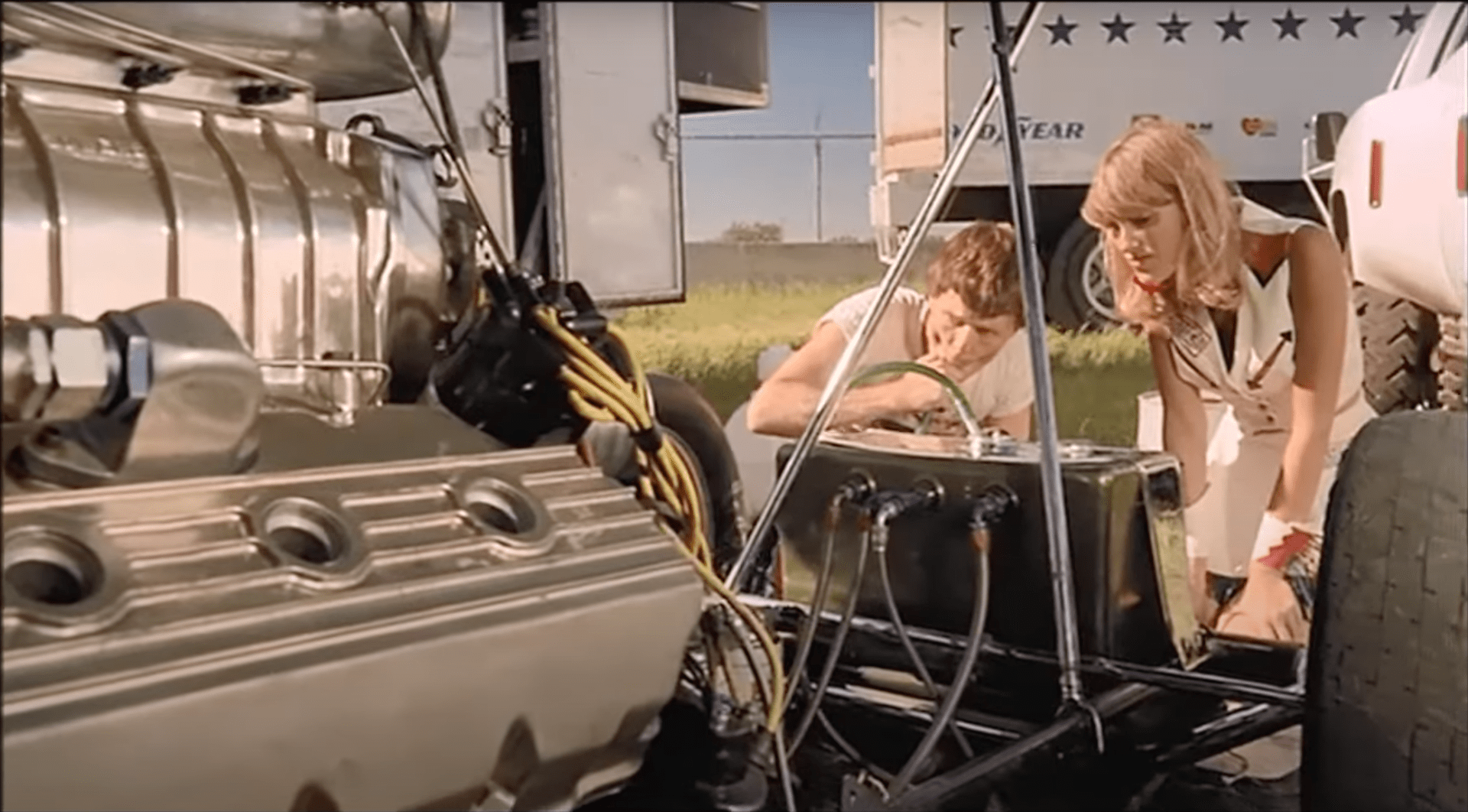

But it’s not an outlier in the Cronenberg filmography, as some have commented. The focus on weird, obsessive, no-apologies subcultures is as evident here as it is in, say, ‘Crash’ or ‘Videodrome.’ And there’s a scene just past the one-hour mark that is pure Cronenberg machine-horniness. The Fred Mollin score goes full sexy rock ballad as manly hands install and tighten and lube and a whole bunch of other stuff. Then there’s the scene where Billy cracks open a can of motor oil and pours it over the chest of one of the two high-heel-wearing hitchikers he picked up earlier in the day. “My boyfriend will kill me,” she purrs. “He hates FastCo.”

But it’s not an outlier in the Cronenberg filmography, as some have commented. The focus on weird, obsessive, no-apologies subcultures is as evident here as it is in, say, ‘Crash’ or ‘Videodrome.’ And there’s a scene just past the one-hour mark that is pure Cronenberg machine-horniness. The Fred Mollin score goes full sexy rock ballad as manly hands install and tighten and lube and a whole bunch of other stuff. Then there’s the scene where Billy cracks open a can of motor oil and pours it over the chest of one of the two high-heel-wearing hitchikers he picked up earlier in the day. “My boyfriend will kill me,” she purrs. “He hates FastCo.”

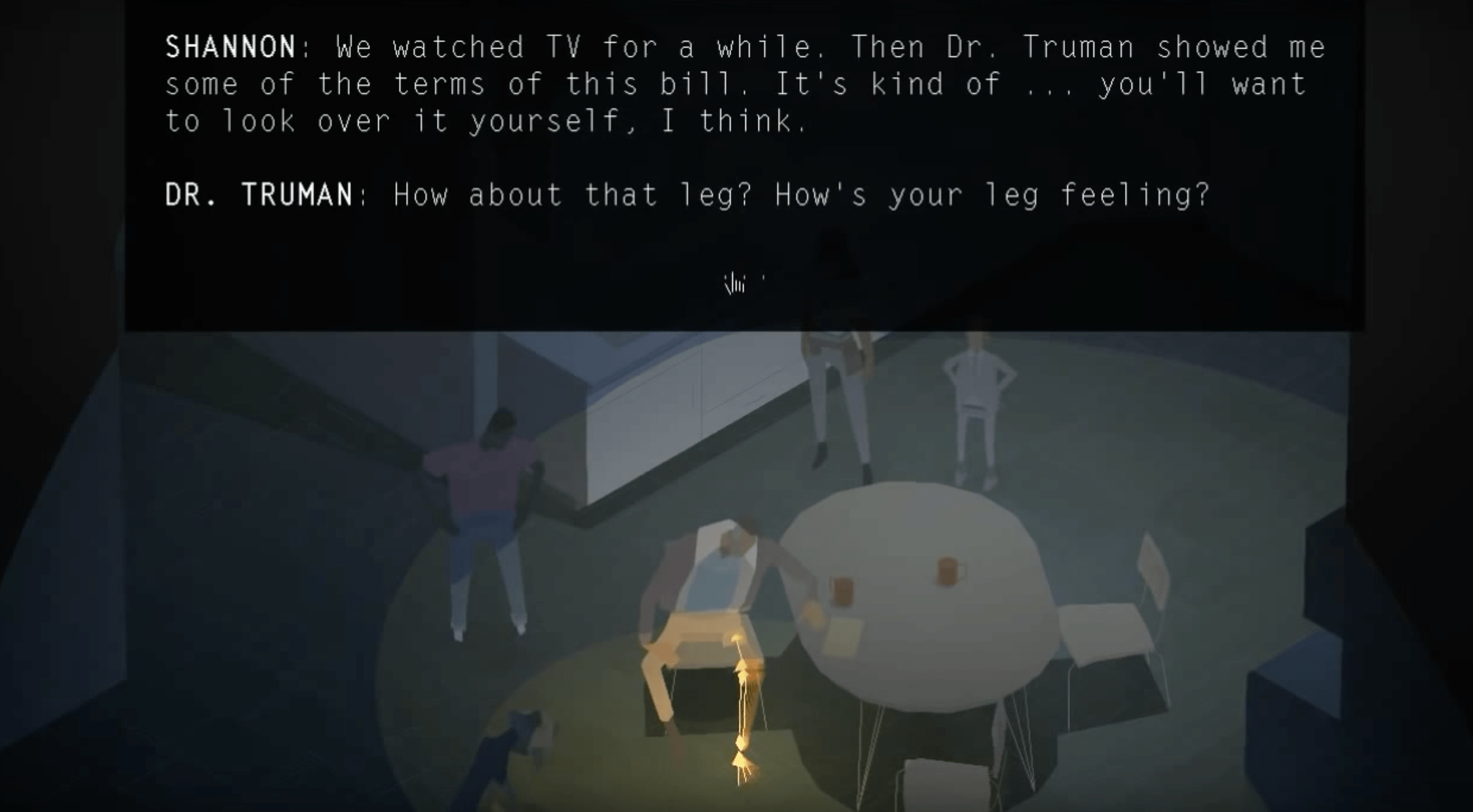

No video games

No video games

Ryan and Sarah, cheating

Ryan and Sarah, cheating