December 18, 2018

This is the eleventh in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

(Spoilers)

EVENING 5: THE SPACE OF PLAY

What we read:

Naomi Clark and Merritt Kopas, “Queering Human-Game Relations”

Hugh Howey, “Select Character” (PS2P)

Austin Grossman, “The Fresh Prince of Gamma World” (PS2P)

Robin Wasserman, “All of the People in Your Party Have Died” (PS2P)

What we played:

Porpentine, With Those We Love Alive

Device 6

What we did:

When I teach students to critically read a literary text, I always start with the text itself. We meticulously inspect the thing, identifying its various formal features—its metaphors, themes, image patterns, narrative structure, and so on. But we never stop there. Understanding a text’s form is just a start. From there, we move into context and ideology. We don’t let that literary text exist in its own special world. I believe that literary texts are intertwined in layered, multifaceted, sometimes difficult-to-detect ways with other texts (sometimes intentionally, as is the case with “intertextual storytelling”), as well as with ideology, history, institutional discourses, the identities and literacies of readers, and so on.

Every text, to recall French critic Julia Kristeva, is an “intertext.”

Some videogame critics don’t like this idea. For these, any talk of history, ideology, politics, gender, or race is a distraction from the thing that matters: understanding how the game works as a game.

Formalism isn’t always intentional. For example, Jesper Juul’s concept of “incoherence” (which I discussed in the last part) is incredibly useful if you’re interested in relating videogames to their players and the wider world in which play occurs. But Juul himself doesn’t explain how incoherence might be approached in terms of, say, gender or class or place.

Just like I do with novels and plays and movie, I believe in a broader definition of the videogame. I believe effective videogame criticism must start with the game itself, but must take into account the contexts in which games are made and played.

This evening was dedicated to mapping the space of play in terms of the ideological, personal, technological, and political forces that shape the experience of videogames. First, we explored how games gamify the physical and social space around the player. Second, we explored how games are embedded in our emotional, ethical, and interpersonal lives. And finally, we utilized queer theory to expand and complicate what we had developed into a more comprehensive, speculative, politically engaged conception of play space.

The object in our hands

We began with a discussion of Device 6, a cool little phone game created by the Swedish developer Simogo. Device 6 is a mash-up of a visual novel and a puzzle game. We play as Anna (well, mostly as Anna, because sometimes the game makes the player part of its fiction), a woman who awakes one fine day, minus memory, on a mysterious island reminiscent of the 1960s television series The Prisoner. We explore the island, encounter various puzzles, some of them head-scratchingly devious, solve said puzzles, and proceed, attempting to solve the big puzzle: Who is Anna and why is she on this island?

To begin, what makes Device 6 a useful entry into an expanded concept of videogame space is the way it gets us to play with text. We don’t just read the text. Sometimes, the text is a path. Sometimes, it is code. Sometimes, it is an object that must be manipulated in some way. (If you want to get a sense of what this is like but can’t play it on your own device, check out this video.)

Device 6 also makes us aware of the device in our hands—the phone or pad. We swipe the screen, rotate the device this way and that, at one point holding the phone up to a mirror to read backward text. We don’t just play the game on the device, we play the device itself.

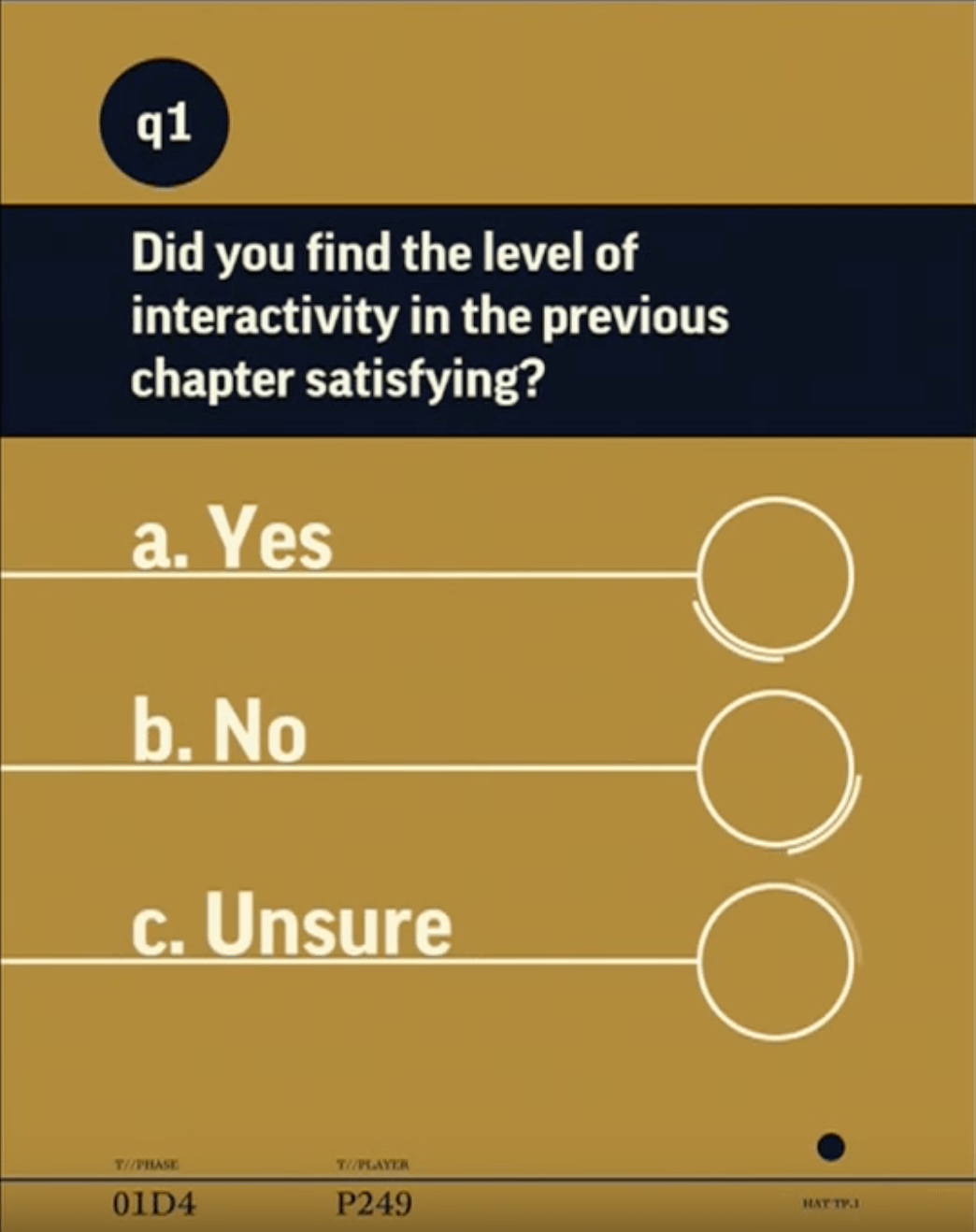

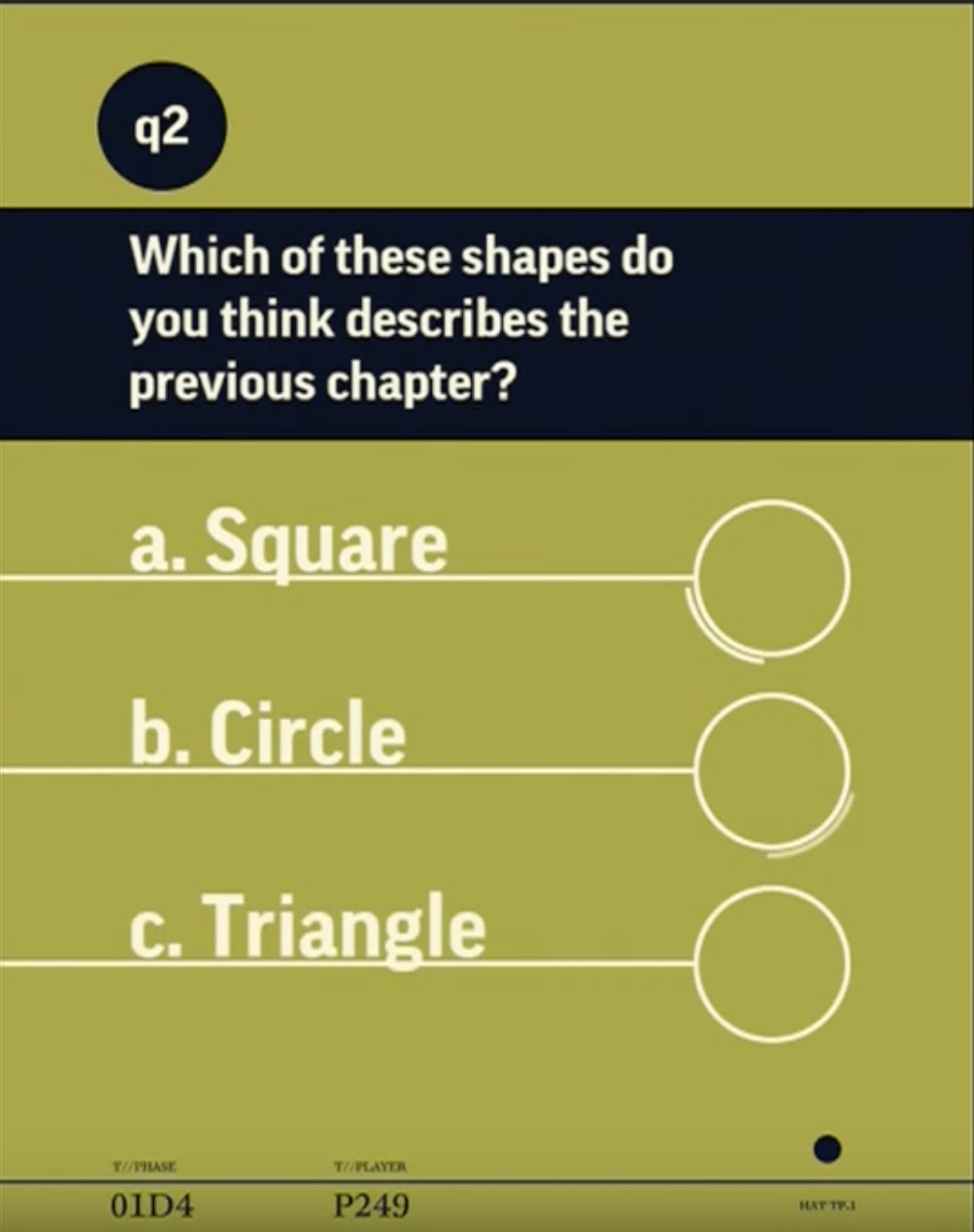

And it makes us aware of our position within networks of power and information. At the end of each chapter, Device 6 breaks the narrative frame and directly addresses the player. We are asked to take a brief survey, for example, or asked to divulge personal information. The game makes us aware of our phone’s interconnectedness with larger networks of power and information.

Ultimately, Device 6 gamifies the spaces of videogame play: the space defined by text on a screen, the space of our bodies interacting with the videogame device, the space of data and social networks.

Literature about videogames

Having established the ways a game might incorporate spaces outside the game text itself into its rules and procedures, we moved onto a discussion of three short stories from one of my favorite collections of videogame literature, Daniel H. Wilson and John Joseph Adams’s Press Start to Play.

Hugh Howey’s “Select Character,” Austin Grossman’s “The Fresh Prince of Gamma World,” and Robin Wasserman’s “All of the People in Your Party Have Died” are about videogames that exist in uneasy and uncertain relationship with the worlds of those who play them.

Stories about the blurred boundaries between videogames and reality are common in videogame literature, so common it’s cliché. We see the trope in the first videogame literature (Tron [1982], Wargames [1983], Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash [1992]) and the most recent (Westworld [2016-present], Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle [2017], Video Game High School [2012-present], Ready Player One [2011]). Why this trope is so common is a subject for another time.

All three stories for this evening explore the blurred boundaries between real life and game life, but map that blurred boundary within troubled emotional and interpersonal spaces.

“Select Character” is about a new mother who ekes out a bit of daily self-care by playing her husband’s first-person military shooter. “What I liked about this game is that you could do whatever you wanted,” she tells us. “Except play as a woman, of course” (490). On a whim, she decides not to follow the game’s macho military narrative, following instead a path of non-violence and generosity, a challenging task in a game designed to reward headshots. On this particular afternoon, her husband discovers that she’s been playing. He’s thrilled, but when she shows him what she’s been doing, he’s confused. “You know the purpose of the game is to score points, right?” he asks (493). What she plays, instead, is “the game within a game. My little solace. A walled-off courtyard with five raised planters. And inside each one, a mix of flowers and vegetables. My flowers. My vegetables” (497).

Grossman’s “The Fresh Prince of Gamma World” is an enigmatic little narrative, intertwining the story of a player character in a post-apocalyptic interactive text game with the story of a young man attempting to survive the inexorable, bruising decline of his family, friendships, and hope. I like how Grossman frames his tale: the narrator found the game Fresh Prince of Gamma World “rattling around the mainframes of Somerville Community College” (412). The game has no historical value, no connection to a larger gaming community. “Written in outdated PASCAL, the code base was just a bunch of data and a homebrew parser for input, eccentrically architected. The game itself is uncredited” (412). Indeed, the story the narrator tells is a story of playing the game in the past. He no longer has access to it and when he searched for it, he tells us, “all I could recover were code fragments posted to a defunct Usenet board devoted to retro games and a user named go4it69 who did not respond to subsequent emails” (412). I also love way Grossman uses the space of the page. The world of the game is represented in one font, the “real world” of the player in another.

As Grossman intertwines the two narrative threads, he also intertwines these font shifts, and when the story ends, we are left with this enigmatic landscape.

“The Fresh Prince of Gamma World” delves deep into the fantasies of masculinity that underwrite so many players’ passion for gaming—and the melancholy that so many players work hard to avoid and deny.

The protagonist of Wasserman’s “All of the People in Your Party Have Died” is a lonely, self-isolating woman who falls in love with a fellow female instructor at a private high school. The story is set in 1988, and the protagonist, Lizzie, is struggling with becoming an adult, with the loss of her liberal optimism, and with pain she feels about the friends she has lost to HIV-AIDS. The sci-fi twist of the story is that the game of Oregon Trail Lizzie plays in order to spend time with her lover without causing undue suspicion is causing actual illness, injury, and death to her students, family, and friends.

Wasserman’s story is an excellent example of what I call “procedural adaptation”: The duplication of a game mechanic in a text such as leveling, respawning, manipulating an avatar, first-person perspective, glitch play, etc. In this case, Lizzie’s efforts to win the game mirror her increasingly self-centered, instrumentalist attitude towards those around her. In the same way that she denies the humanity of the people in her in-game pioneer party, she denies the humanity of her students, her family, and, ultimately, lover. “This is what it feels like to survive, Lizzie told herself. It felt lonely, but it was what she’d chosen, she thought, so she must have wanted it that way.”

Our discussion of these stories marked the moment when we began to think seriously about why literature about videogames is as important as videogames themselves. Howey, Grossman, and Wasserman map the shadowy, shifting spaces in and around videogames the way only fiction can. They map spaces of memory, consolation, jealousy, and rage. They map spaces of sharing, desire, betrayal, and regret.

And they remind us that, while not all videogames tell stories, every videogame player has a story to tell.

Queering human-game relations

To review, this evening started by exploring how games gamify the spaces around us by talking about Device 6. We then delved into how games insinuate themselves into our lives—and vice versa—by discussing the short stories by Howey, Grossman, and Wasserman.

It was time to tie these ideas together, and to help us in that, we turned to Naomi Clark and Merritt Kopas’s essay “Queering Human-Game Relations.” I can’t recommend this essay strongly enough and urge you to read it or watch the live (and unabridged) recording of their keynote to the 2014 Queerness & Games Conference.

Clark and k (merritt k is now her preferred name) investigate how videogames function as representational systems, how players relate to games and other players, and how videogames replicate and complicate normative ideologies of gender and sexuality. To accomplish this, they explain how games can be “queer” and how players and play communities can engage in “queering” practices.

NOTE: If you’re not familiar with the terms “queer” or “queering” as they’re used by academic critics, the first thing to know is that neither term should be used casually, especially if you’re straight (which I am). Even in the LGBTQ+ community, the term can sometimes be controversial, even though the “Q” in “LGBTQ+” stands for “queer.” I’ve been chastised on more than a few occasions for using the word, usually in situations where I was unable to provide a full background on the term or failed to alert my audience to the hazards of using it casually. I proceed here with semantic caution.

Typically, when we call a game “queer,” we speak to the game’s content: the presence of LGBTQ+ characters, for example. While Clark and k agree that queer content in games is important, they don’t want to stop there. As Clark explains, “Queer is a word in a constant process of mutation, inherently unfixed.” Further, “it’s inextricably bound up with the idea of resisting dominant, naturalized narratives and categories . . .” Storylines and characters are important, yes, but videogames are much more than storylines and characters.

It’s relatively easy to identify a queer character or a same-sex romance, but “it’s not as easy to pin down what exactly a queer mechanic looks like.” As k explains, “Taking a mechanical or rules-based approach to queerness is harder than looking at narrative . . .”

They build on the work of Miguel Sicart, a game scholar who argues that playing a game is an inherently ethical activity, especially when it involves, in Clark and k’s words, “playing with, testing, and perhaps even rejecting” the premises and processes of the game. Designers can do that, too. Clark and k cite the work of Paolo Pedercini and Avery Alder, who design games that make us aware of the way games reinforce dominant, damaging values. They cite Edmond Chang and Robert Yang, who are concerned with “how rarely conversations around queerness and difference in games delve to the level of code.”

That’s where Porpentine’s gorgeous, creepy, and deeply moving Twine game With Those We Love Alive comes in. I don’t want to give too much away. Go and play it. It’s free and doesn’t take long. You can find it here. While I love the story that Porpentine tells, what I love most about it is the way the game pushes against my desire for progress. The first time I played the game, I felt stuck. There were periods where I just kept doing the same thing over and over. I wasn’t progressing. I was getting bored, frustrated. Then I realized that that was the point.

In a sense, the game glitches both the narrative of heroic overcoming and game mechanics that treat the gameworld like a puzzle. The world of WTWLA is not a puzzle to be solved, but an emotional situation to be endured.

I also love the way WTWLA incorporates my body into its mechanics—it literally asks players to gamify their breath and their flesh. We’re asked from time to time to draw on our skin, to inscribe sigils that memorialize significant moments in the game. You can see a gallery of player sigils here. There is something intensely embodied about drawing on our own skin. And there is a thrill to walking out in the world with these enigmatic sigils on our hands and arms and legs. We bring our experience in Porpentine’s world into our world.

WTWLA is a perfect example of a “queer” videogame. It reminds us that, if we’re going to talk about how games represent gender and sexuality, we need to talk about content (storyline, characters, themes, dialogue, settings, etc.), but we also need to talk about mechanics (choice, movement, leveling, agency, etc.) and player performance—what players do, what they imagine they’re doing, who they’re doing it with, where they’re doing it.

Clark and k want us to think about how power works in games. They want us to think about open-world games like Skyrim and Minecraft, worlds players “are almost completely free to modify at their whim, one whose only other inhabitants are violent monsters and animals whose bodies can be used for various purposes.” They want us to think about the ways games reward goal-oriented behavior, what Paolo Pedercini calls the “aesthetic form of rationalization.” They want us to question the idea that games teach us that failure is okay—that when we fail, we must try and try again. They remind us, “For kids on the receiving end of losses, especially kids made to feel incapable in other realms, the experience of failure isn’t one of freedom or escape. It’s a reinforcement, a reminder.”

Clark and k want us to be open to different kinds of games but also to different ways of playing games: “Mutating, breaking, and twisting games are valuable actions insofar as they help make visible our assumptions about play. As Pedercini puts it, this is a ‘slow and collective process of hacking accounting machines into expressive machines.’” If we can do this, then maybe games really can help us play our way out of game space into a better future.

This post skillfully weaves the threads of videogames and literature, creating an exploration that parallels the changing dynamics in gaming culture, like a Cyberpunk Jacket flawlessly woven into a futuristic story. Thanks for Sharing.