November 10, 2022

This is the eighteenth in a series of posts dedicated to works of playful literature and theater—not just games that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another games, game players, and game culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, though one that’s more focused on videogames rather than games more generally, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

Car-racing movies are a fascinating example of the stories we tell with, about, and around games. They’re certainly plentiful. IMDB lists 130 films under the category “car-racing,” a list that is neither complete—notably missing is Kenneth Anger’s experimental short Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965)—nor includes movies that don’t focus on racing, but where racing is dramatically significant, as in Carnival of Souls (1962), Amarcord (1973), or Grease (1978). The earliest is 1913’s The Speed Kings, a bit of romantic fluff featuring two of the biggest racing stars of the era; the most profitable the Fast & Furious franchise, which has earned more than $6 billion in global revenue, up there with Harry Potter, James Bond, and the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

My exploratory dive into these movies is part of the research for a book I’m writing on the relationship between play and literature. If you’re interested in seeing what I’ve developed so far, you can find an essay on videogames in film here, on individual texts that center gameplay such as this essay on The Queen’s Gambit, and the forthcoming anthology I’m co-editing with Megan Amber Condis on the stories we tell with, about, and around videogames, though that won’t be on shelves for another year or so. To this point, I haven’t yet focused on my scholarship on a specific game—and car-racing movies seemed as a good place to start as any, particularly since they’ve received little attention from scholars, and my wife and I have recently become fans of Formula One, appropriately enough due to a documentary film series on the sport, Drive to Survive.

Before I dove in, I needed to trim the list—I wanted historical scope to my viewing, but didn’t have time to watch 130 movies, especially given that I wasn’t sure it would be worth the effort. So, I went with a hunch and decided to focus on the 53 films listed on IMDB between 1960 and 1980 (here’s the list), a period when sports, games, and movies underwent significant change—as did the automotive industry and the cultural significance of the car.

The movies I watched were a mix of the classic, the oddball, and the available, with strong bias towards English-language, U.S.-made movies. They varied in terms of the kind of racing they portray: Grand Prix, drag racing, stockcar, endurance, the figure eight, off-road, rebels versus cops, and so on. They varied in quality, budget, and audience, too: luxe affairs like Grand Prix (1966) and Les Mans (1971); grindhouse flicks like Fireball Jungle [1968] and Death Race 2000 (1975); gritty noir tales (The Killers [1964]); Lynchian death drives like Pit Stop (1969); middle-of-the-road melodramas (Winning [1969], Bobby Deerfield [1977], Fast Company [1979]); biopics (43: The Petty Story [1972], The Last American Hero [1973], Greased Lightning (1978]); documentaries like Seven Second Love Affair (1965) and One by One (1975); and bubblegum pop like Speedway (1968), Bikini Beach (1964), and the Herbie the Love Bug series (1968, 1974, 1977). And no, quality does not correlate with either budget or audience.

The hunch paid off. What I’ve written here reflects my initial thoughts on the films—it’s a genuine essay. If you’d like to take a look at my reviews of individual films, see LINK. I haven’t watched every movie on the list and only a dozen or so released after 1980 or before 1960, so this is all quite tentative. I invite you to share your perspectives, criticisms, and recommendations with me, either in the comments section or by reaching out to me on Twitter (@mike_sell).

There are four things that strike me about these films in terms of how they tell stories with and about the sport of car racing. They each speak to the relationship between the particular attitudes and athleticism of the sport and the industries in which they are embedded. They tell stories, both individually and as a body, about high-speed performance, individual achievement, and capitalism in drift.

Who they’re about: straight, white, macho men

These are movies about straight macho men doing straight macho things, most of which involves cars, though attractive, attentive women are almost always nearby. With few exceptions, the movies don’t offer much in terms of critical perspectives on either masculinity or patriarchy. There are exceptions—The Young Racers (1963), The Wild Racers (1968), and Winning come to mind. But in general, when these movies have something to say, it’s with masculinity, not about masculinity.

It is a profoundly precarious masculinity, a masculinity strapped into loud, dirty, fast machines, machines that break down, spin out, crash, explode, and burn, often quite spectacularly. It’s a masculinity encased in fireproof suits, helmets, and steel—and in bodies that are dirtied, battered, bruised, concussed, and broken. The dramatic conflict usually centers on whatever can intensify that thrilling precarity: dangerous people, unscrupulous capitalists, romance, grief, new technologies, rivalry, existential angst, the cops, the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Though they are never gory, the obsession with damaged bodies and cinematic sensationalism aligns it with another subgenre of the period, so-called “splatter horror.” Herschell Gordon Walker’s Blood Feast (1963) and Two Thousand Maniacs (1964) demonstrate a similar fascination with violence, the laboring body, and intense, anti-social modes of desire.

Two, these are stories about white men. Greased Lightning (1977), a biopic about Black American racer Wendell Scott starring Richard Pryor and directed by Michael Schultz, is the one exception. Vanishing Point (1971) co-stars Cleavon Little as blind DJ Super Soul, a performance I’ll discuss later, but for the most part, non-white characters are few and tertiary: Toshiro Mifune in Grand Prix (1965), George Takei in Red Line 7000 (1965), Benson Fong in The Love Bug (1968), Poncie Ponce in Speedway (1968), Chuck Daniel in Fireball Jungle, and those who appear briefly (often uncredited) as waiters, housecleaners, maids, and other menials. (If I’ve missed any movies or performers, please let me know!) The whiteness of these movies is neither surprising nor unique to car-racing movies—there were few opportunities for BIPOC artists in the film industry. The same can be said about automotive sports of the period, which, with a few exceptions, were segregated.

Whiteness is rarely explicit; rather, it’s ambient, systemic. It’s occasionally treated more directly, as with so-called “Hixploitation” flicks like Fireball Jungle and Checkered Flag or Crash (1977) that traffic in white-trash stereotypes. Confederate flags appear briefly in One by One, The Last American Hero, and Corky (1972), also on the posters for Corky and Eat My Dust! (1976), though no confederate iconography appears in the latter.

The third act of Thunder in Carolina (1960), which takes place at the Southern 500 in Darlington, South Carolina, is literally festooned with the stars and bars of white supremacy, and the action concludes with as Mitch and Buddy driving into the sunset to the triumphant strains of “Dixie.” However, in general these are films in which the absence of people of color is what Toni Morrison might call a palpable absence, a purposeful and uncanny displacement.

How they tell their stories

If my first two critical takeaways concern who these movies are about, the second two are about how they tell their stories. To begin, these are action movies, and those that focus their dramatic attention elsewhere (i.e. melodramas like Winning and Bobby Deerfield) still have major action sequences. These are kinetic, noisy affairs, extravaganzas of movement, color, and sound. Crashes are mandatory, explosions if affordable.

Not coincidentally, car-racing films are drivers of technical innovation—and from the very start. The Speed Kings used car-mounted cameras to put the viewer in the middle of the action, sometimes pointed forward in point-of-view perspective, sometimes backwards to capture a driver and their agon. But the exemplar is Grand Prix. Rejecting the usual tricks of the genre (rear-projection screens and sped-up footage), Director John Frankenheimer and Director of Photography Lionel Linden devised a repertoire of camera angles, engineered a variety of on-board camera mounts (including one with a remote-control pan-and-tilt), made liberal use of helicopter shots to give the viewer a sense of the encompassing space of the action, and utilized split-screen compositions to take advantage of the ultra-widescreen format in which it was filmed.

Responsibility for capturing the action belongs as much to the editor as it does to the camera operator. The most technically adventurous example is The Wild Racers (1968), edited by Vera Fields, who would later work with Peter Bogdanovich, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg, winning an Oscar for her work on Jaws (1975). I haven’t found a shot in the film that lasts longer than ten seconds, and diegetic sound is regularly out of synch with what we’re seeing. The effect is both disorienting and seductive, communicating both the dynamism of the Grand Prix race circuit and the proleptic psychosexual drive of its protagonist, Jo Jo Quillico. But even the most rushed and budget-constrained car-racing film aims to disorient and thrill.

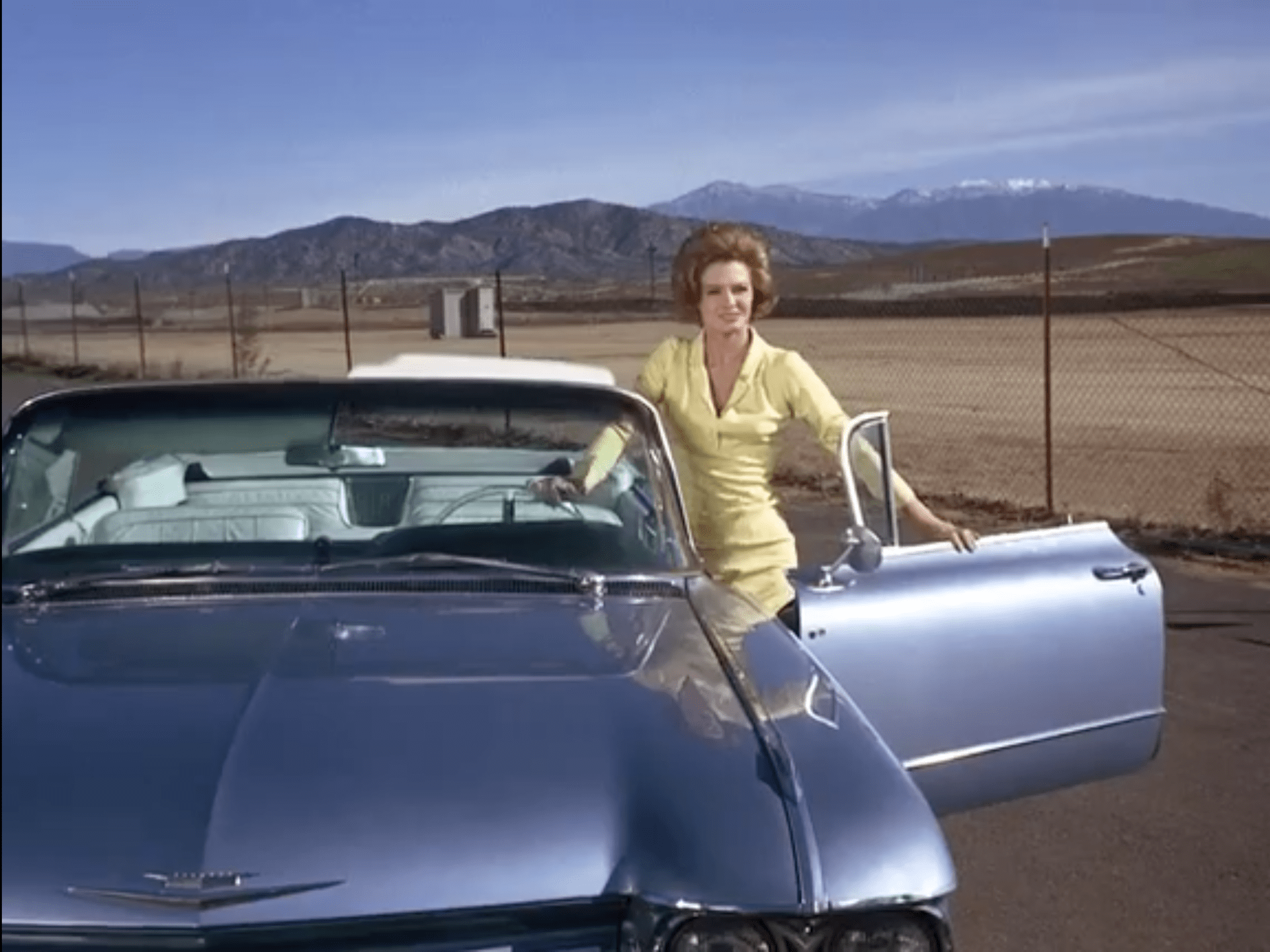

The titillating thrills of these films aren’t just about the action. These are fetish films. The camera lingers over vibrating engines, buffed and gleaming chrome, grease-stained hands, sweaty brows, veiny forearms, denim-clad asses hanging out of the dark recesses of internal combustion. The key to this particular code of automotive pleasure can be found in Kenneth Anger’s short film Kustom Kar Kommados.

Anger’s description of the project could be a manifesto for the genre. The car, he writes, possesses a “dual aspect of narcissistic identification as virile power symbol and its more elusive role: seductive, attention-grabbing, gaudy or glittering mechanical mistress paraded for the benefits of his peers” (qtd. in Cargle 24). Its three-minute run is almost entirely focused on a good-looking young white man attending to the gleaming black and chrome surface of his custom car with a perfectly spotless white feather buff. The action is set against a vivid candy-pink backdrop that melts into the mirror-like black and silver of the vehicle.

For anyone who’s watched a bunch of car-racing movies, all of this is familiar to the point of being cliché, just a lot more up-front about what’s at stake. Most of the time, the kink stays well within the bounds of Hollywood convention and bourgeois taste. The gorgeous actors, immaculately tailored clothing, witty patter, and romantic complications of Howard Hawks’s Red Line 7000 are kink for the department-store lingerie crowd. But sometimes, the kink is just plain kinky. David Cronenberg’s Fast Company (1979) features a scene that might have been stolen from a dog-eared copy of Penthouse Forum. While traveling to their next race, the FastCo team runs across two scantily clad, stiletto-heel-wearing hitchhikers.

Yes, seriously.

After checking out the crew members, the women jump into the team trailer for a round of “sexy” fun. “My boyfriend will kill me,” one of them purrs as motor oil is poured over her breasts, “He hates FastCo.” In the erogenous mise-en-scène of the car-racing film, women typically feature as prize, rewarding the winner with a kiss. When not a prize, they’re an ornament. Yes, there are a few movies in which, though initially positioned as prizes or ornaments, female characters subvert expectations.

Angie Dickinson’s turn as femme fatale Sheila Farr injects a note of menace into the proceedings. Mary Woronov’s Calamity Jane in Death Race 2000 (1975) is devious, dangerous, and entirely unconcerned with the men around her except as opponents. And there’s Darlene in Eat My Dust! (1976), the smarter-than-we’re-led-to-think rich girl Hoover wants to impress with his high-speed derring-do, but who’s just along for the ride. “It wasn’t me at all, was it?” he asks as she walks away into the Halloween night. Charlotte Rampling’s cameo in Vanishing Point (1971) has a different vibe but similar effect—she’s mysterious, almost spectral, promising a moment of sensual respite from the amphetamine-soaked drive that will take Kowalski to his death, but she disappears into the darkness and he returns to the road.

Finally, there’s Jack Hill’s Pit Stop. In a sequence that could have been directed by David Lynch, we’re introduced to Ellen McCleod, played by Ellen Burstyn in one of her first film roles. The scene begins with our anti-hero Rick walking towards us, the camera backing into some kind of storage room, broken arm in a sling, head reeling from a concussion. We hear a buzzing, crackling sound; light flashes from somewhere.

As Rick moves deeper into the space, we begin to hear a droning sound, though it’s unclear whether it’s diegetic. The shot switches to Rick’s point of view: a wall of cabinets, boxes, barrels, a fork lift, crackling light just beyond, the droning sound building in volume.

We then switch to a crane shot, the camera following Rick from above as he steps among shelves groaning with engine parts, tire rims, and tools. Rick steps into a room, the flash and crackle and drone reaching their peak. We see a figure in a welding mask, light and smoke broiling around them. Rick calls out, but his attention is drawn to the job, first in admiration, then confusion: “That’s really nice. But it’s a 289. How come you don’t go with the 390?” The figure removes their mask; it’s a woman, hair cut short. “289 is 200 pounds lighter. Way we have that set up we get 350 horse power out of it.”

She puts the mask on the table, removes her coveralls, revealing her team uniform. Rick grows visibly confused and (judging from his raised eyebrow) titillated by the combination of knowledge, skill, and beauty. What I find fascinating about this sequence is that it positions a woman in the sanctum sanctorum of race-car masculinity, the garage, and, though it troubles the signs of gender, it doesn’t go for simple titillation. It’s the cinematic obverse of Kustom Kar Kommandos, a denial of the codes of straight-male visual pleasure. Ellen is neither a pin-up nor a pushover. Her agency as a character is established both visually and verbally, and that agency is sustained for the rest of the film.

The car-racing movie as Pop artifact

Kink duly noted, the genre’s obsession with surfaces feels very much of a piece with the broader Pop movement. Elvis Presley’s two car-racing movies Spinout (1966) and Speedway (1968) are the apotheosis: brightly colored, relentlessly blithe, at time horrific (in Speedway, Elvis’s best friend is a relentless sexual predator), profoundly cynical manipulations of the intertwined sign systems of racing, romance, and youthful hedonism. A more self-conscious, if no less nihilistic deployment of the Pop aesthetic can be found in Claude du Boc’s horny 1975 documentary One by One (1975), especially the scenes that juxtapose the intense professional focus and high stakes of paddock and pit with the commercial bacchanalia that surrounds it.

The Pop looks of these films is of course a conscious design decision—a choice to highlight signage and saturate color—but it also speaks to structural shifts in the sport, and sports more generally, that changed the way car races looked. Car racing in the 1960s was a sport transformed by the emerging industrial-entertainment complex, a globalizing automotive industry, and the relentless eroticization of the car and its associated parts by advertisers. Whether glamorous or gritty, the surfaces of car racing were increasingly organized by the iconography of corporate capitalism. A filmmaker wishing to tell a car-racing story without a bunch of ads in frame was going to have a hard time of it–and that was true pretty much from the beginning of the genre. The Speed Kings was essentially an ad for the sport, the product being the racers themselves.

It’s not clear why a storyteller would want to avoid it in the first place: the sport itself was a profit-generating venture from the start, made possibe by one of the iconic products of US industrialism: the car. That product was particularly iconic during the 1960s and 70s, featuring as prominently, glamorously, but also mundanely as other products of the era: cigarettes, television, whiteness, femininity. It’s in that erotic mash of commodity culture and the precarious white male body that we can detect a deeper aesthetic and philosophical connection to Pop: repetition.

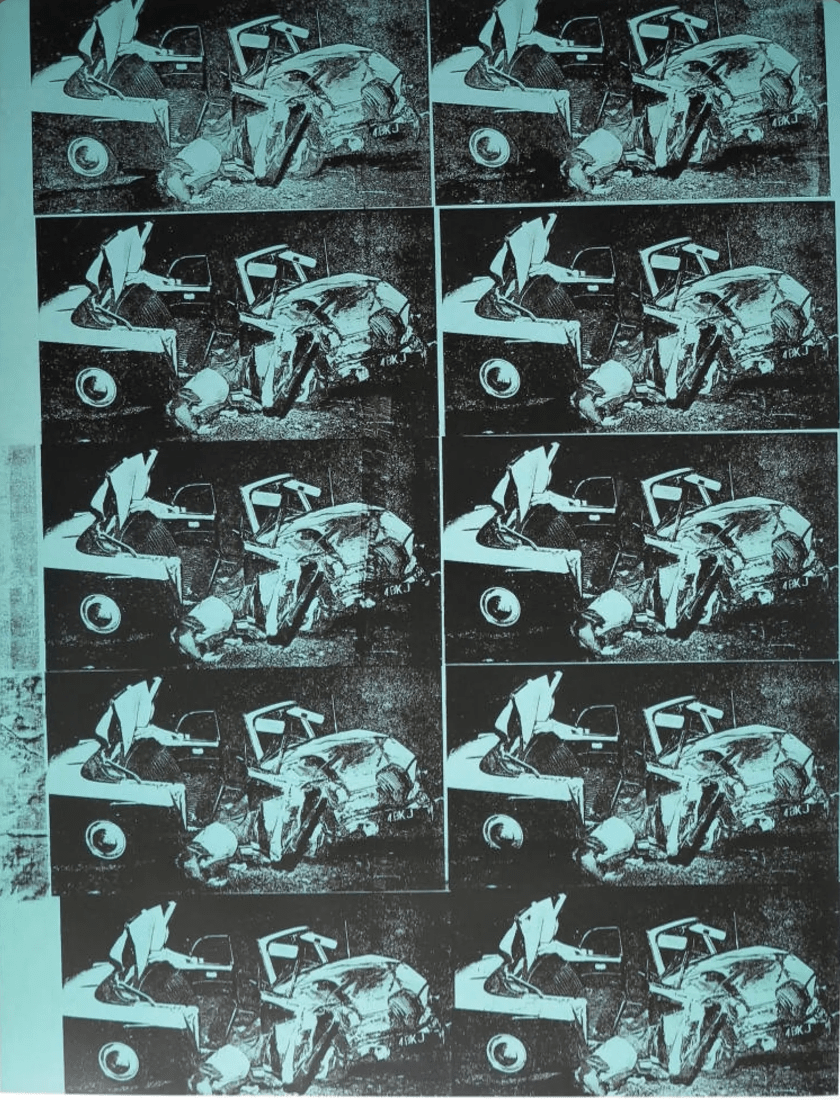

Andy Warhol provides the most familiar examples. He not only created multiple versions of images, but displayed them to foreground similarities and differences among them.

On one hand, repetition communicates a democratic sensibility. Warhol speaks to this in his 1975 book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: “You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.” Car-racing movies communicate a similar attitude. Though a car might cost a lot more than a Coke, it’s within reach of Everyman, the admen tell us, especially those with guts and a willingness to do a little weekend tinkering. The heroes of Greased Lightning and The Last American Hero (1973), both stories of true-life racing legends rising from the margins to the top of their sport, are Warholian figures, finding fame and fortune in industrial capitalism’s most desirable and dangerous product.

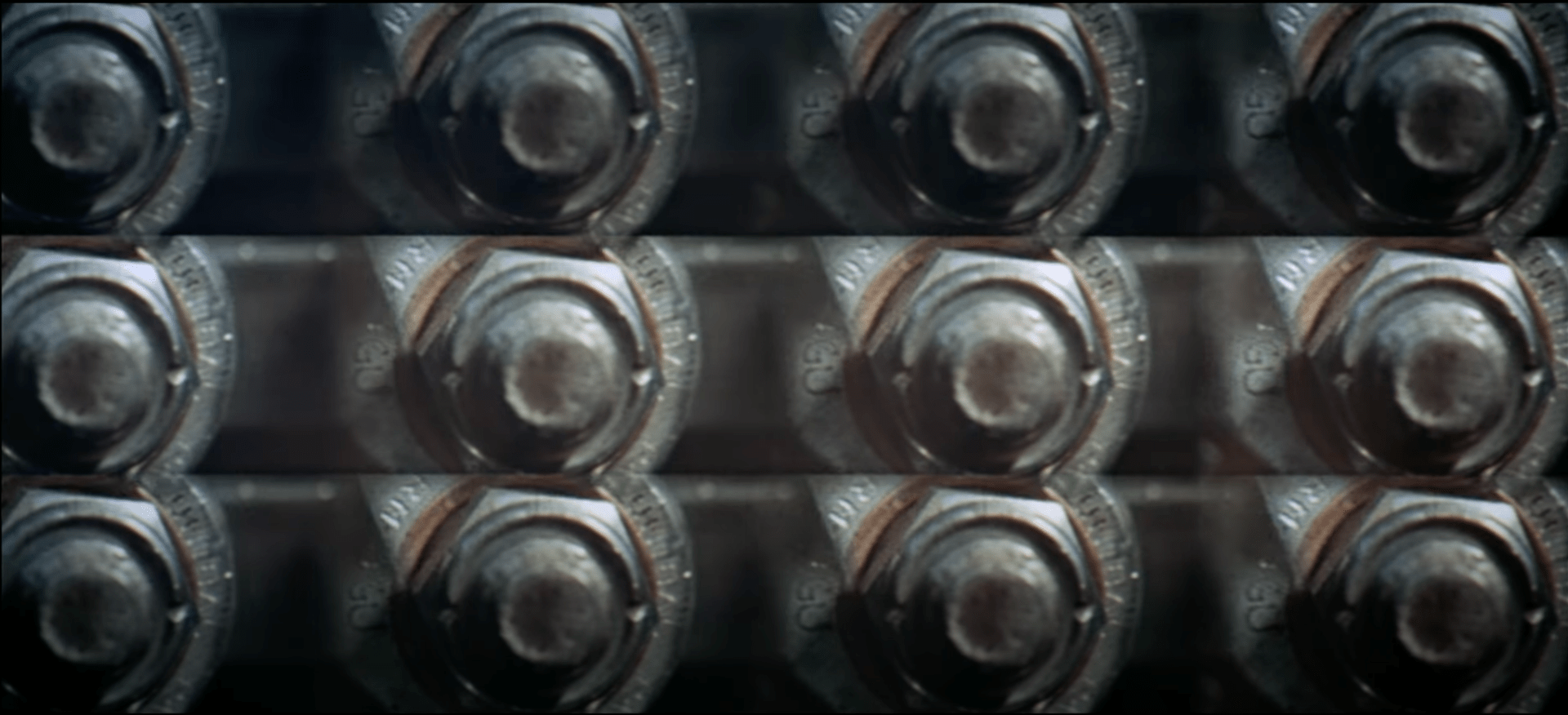

But it’s a dangerous rhythm, less an aesthetic than a drive. Repetition is the elemental aesthetic of the car-racing film, most evident when we’re in the middle of the race: every driver anonymized in the very moment of individual performance by fireproof suit, helmet, protective goggles, and automobile. Repetition is action in racing movies, the speed of the sport communicated with car after car passing in a blur and a roar. Drama becomes pure splatter in these moments, shedding recognizable trademarks for action painting and abstract expressionism. Saul Bass literalizes this in his brilliant title sequence for Grand Prix. Instead of following the normal convention of repeating a shot in temporal sequence (one engine after another, one hand after another, one car after another), Bass duplicates a single shot in a geometrically ramifying grid.

There’s something morbid about all this repetition. Bass’s grids appear before and during races—their rhythmic abstraction inextricable from disaster—cars crashed, bodies wrecked. The first time we see it in action precedes the grievous injuring of one racer and the concussive launching of another into the waters of Monaco’s Port Hercule. Death haunts the genre. By Brad Spurgeon’s count, of the 30 real-life racers that appear in Grand Prix in small roles, cameos, or as extras, 13 died in subsequent racing accidents. The documentary One by One pulls a particularly lurid on mortality. The film begins with a sequence showing a race official getting hit by a car while attempting to help a crash victim. A later sequence focuses on François Cevert and the luxurious life he enjoys on the Formula One circuit. Shortly after filming, Cevert would be killed in a horrifying crash at Watkins Glen, his body bisected by a safety barrier. During these two decades, some six dozen racers were killed in accidents (Wikipedia). But those account for only a tiny percentage of automobile-related deaths. In the US, driving fatalities rose from 36,399 deaths in 1960 to 53,543 in 1969, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

The pain and horror haunting these films speaks to the more uncanny registers of Warhol’s work. We think of the Marilyn Monroe series, her face speaking to rubber-steamped exploitation, depression, and death. But perhaps the more apt comparison is the Death and Disasters series, which figures in its use of silkscreen printing and multiples the perverse relationship between singular, tragic horror and numbing statistical recurrence, most resonantly in the images he made of car crashes.

The race track as chronotope

One way to understand repetition is as an “affordance.” In her book Forms (2015), Caroline Levine defines affordance as “the potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs” (6). To borrow two examples from Levine, glass “affords transparency and brittleness” and rhyme “affords repetition, anticipation, and memorization” (6). As I’ve explained in detail elsewhere, texts that adapt games often borrow the specific mechanics and procedures of those games, adapting them to move the narrative forward or create affective intensity.

The most obvious affordance of car racing is the race route itself. Whether street circuit, drag strip, banked oval, road race, Grand Prix circuit, or figure eight, the most dramatic moments of a car-racing movie take place on the track and those moments are molded by the built-in drama of corners, chicanes, and straightaways. A movie in which the racing occurs on an oval track tells its story differently than a road race. The pit is a flexible dramatic device. In racing, the pit is the place where advisers and mechanics are set up to provide in-race repairs and adjustments. In car-racing movies, the pit provides a handy excuse for dramatic interludes in the kinetic action.

The track provides a number of these affordances. Like the baseball field, the pool hall, the boxing arena, or the casino, the track is an elegant narrative geometry, divvying the drama among the drivers in their cars, the crews in the pit, and the spectators in the stands. The spectators and crew serve several useful narrative functions. They help us track the forward movement of the race, their heads turning to follow the action. Similarly, their dialogue tracks the drama, whether it’s the race announcer identifying who just crashed, the mechanic worrying out loud about tire wear, or the women commiserating over their shared fate as race wives. They also provide a way for sound designers to modulate the noise, shifting from the roar of racing to the urgent verbalism of the pit-stop confab.

In sum, the race route is what Mikhail Bakhtin calls a “chronotope,” a particular configuration of time and space that both supports and is produced by storytelling. In movies that adapt game affordances, this is typically enabled by the adaptation of the particular “constitutive rules” of the game. In other words, movies have to follow the same rules of everyone else who’s participating. In car racing, that’s the drivers, their crew, their friends and families, and the fans. Except that a movie can cut from one to the other.

The race track is a map of affect. Characters communicate feelings: worry, fear, horror, boredom, anticipation, elation. They do so differently depending on who they are. There’s the driver, typically stern if not blank-faced. There are the guys in the pit, their expressions modulated according to rank and experience. They’re the best informed, as the pit is a place where data is gathered and team-decisions made. There are the folks in the stands, cheering, gasping, shouting. They tend to be less analytic, more passionate. But regardless of where they’re watching the action from, they surrogate our feelings, amplifying or complicating our experience of the action.

Cleavon Little’s performance in Vanishing Point is a particularly interesting example of such surrogation. Little plays Super Soul, a blind DJ in a sun-bleached town in the middle of nowhere, Nevada. As Kowalski zooms westward, Super Soul updates the KOW audience on the situation, plays some truly heavy rock ‘n’ roll and soul tracks, and slips Kowalski coded tips on how to avoid police traps down the road. Little plays him as both shaman and shaker. After his radio station is wrecked by racist, pro-cop thugs, he changes his radio station’s name from its call sign (KOW) to the hero whose epic he’s been singing: “This radio station was named Kowalski, in honor of the last American hero to whom speed means freedom of the soul. The question is not when’s he gonna stop, but who is gonna stop him.” Though Super Soul has a narrative function comparable to the so-called “Magic Negro” trope, he also serves as a conduit to the community around him, providing information and soul.

The race track can serve as metaphor, too. Vanishing Point puts there’s in the title, referencing both the optical illusion produced by the intersection of straight road and horizon and Kowalski’s existential struggle.

His epic journey is defined by the route in terms of both its itinerary (Denver to San Francisco in two and a half days) and environment (the road network of the western U.S.). Following a similar route at similar speeds two decades later, Jean Baudrillard writes, “Speed is . . . the rite that initiates us into emptiness: a nostalgic desire for forms to revert to immobility, concealed beneath the very intensification of their mobility.” For Kowalski, as for Baudrillard, velocity is a ritual, “a space of initiation which may be lethal.”

In Pit Stop, Jack Hill treats the figure-eight, an absurdly dangerous track that requires drivers to pass through an intersection, as a figure for the Faustian bargain Rick strikes with team owner Grant Willard.

That shape is contrasted sharply when the scene shifts to the racers and their friends zipping and zooming across the endless white-sand curves of the Imperial Sand Dunes, a moment of almost lyrical intensity that enables Rick and Ellen to deepen their relationship. No longer bound to the figure eight, they can escape the bounds of their personal and professional loyalties.

Drifting into late capitalism

The car-racing film is about men modifying machines, using machines, and getting mangled, killed, or rendered undeniably attractive by machines. It’s a profoundly romantic genre: boy goes fast in car, car injures boy, boy adjust car, boy goes faster in car. Cyborg romance at dangerous speeds. It’s hard to find a movie one this list that doesn’t stage at least one scene involving guys talking technobabble while they massage bolts and wrestle with hunks of metal and rubber. They might not have a white feather buff like the young man in Kustom Kar Kommandos, but they know the feeling.

Sometimes the techno-babble is the entire focus, as in the documentary Seven Second Love Affair. Director Les Blank tells the story of a man/machine romance in the middle-class suburbs and drag strips of Southern California. Rick Stewart and his crew and family are portrayed in a way that reminds less of the Hollywood hero and more of garage tech-bros like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak of Apple Computer fame. The death drive of the sport is no less evident here: drive, recalibrate and repair car and body, drive again, this time faster.

So, where does this lead us?

There’s a technique in racing called drifting. It’s when a driver oversteers into a corner at high speed, causing the car to enter into a controlled slide, the front wheels pointed in a direction opposite that of the turn, until the turn is complete. Car-racing movies are stories about straight white men drifting around late-industrial capitalism, talking technical statistics and personal grudges with like-minded obsessives with relatively identical chips on their shoulders and women on their arms. These are stories about straight white men attempting to control a slide through imminent disaster in a machine designed to turn the human being into velocit. It’s a lot of fun watching them do it—even more fun when they fail. It’s a classic return of the repressed–of industrial overproduction, designed-in obsolescence, the emergence of the Japanese auto industry, and the Civil Rights and feminist movements.

These are kinetic morality films for the narrow-minded. Infernal metal, rubber, and glass are the reward for those who fail. For the winners, the reward is more racing and, if they’re lucky, the girl.