November 20, 2020

This is the seventeenth in a series of posts dedicated to works of playful literature and theater—not just games that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another games, game players, and game culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, though one that’s more focused on videogames rather than games more generally, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

SPOILERS! In this post, I discuss pretty much all of the major moments in the series. Watch first, then read. And please leave a comment. I’d love to read your thoughts on all of this.

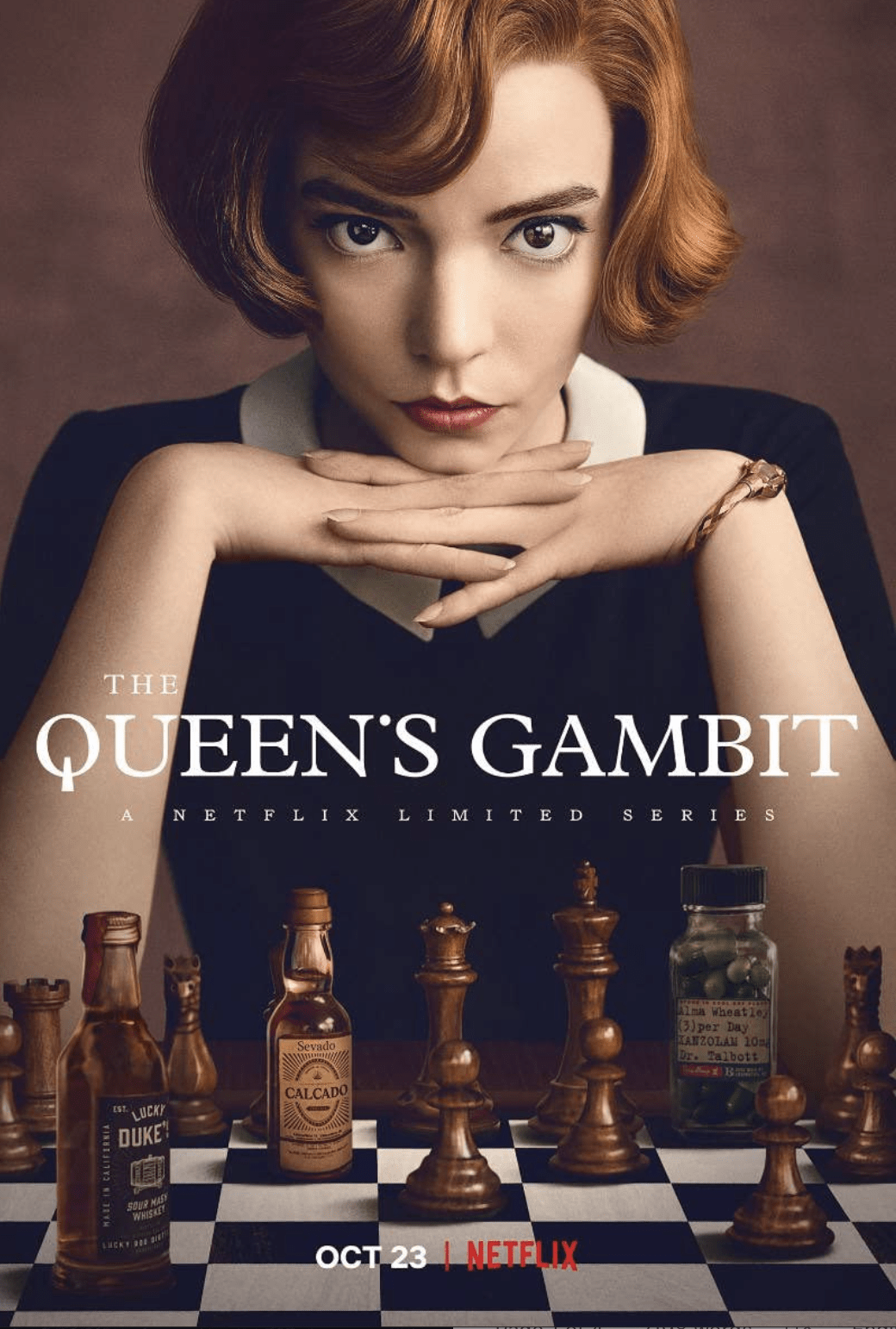

Like just about everyone else these days, I’ve found The Queen’s Gambit perfectly delicious. The seven-episode Netflix miniseries created by Scott Frank and Allan Scott is the epitome of bingeworthy television. The script is propulsive, dropping story beats with clockwork precision. It’s gorgeous to look at, thanks to the camerawork of Steven Meizler, the production design of Kai Koch, and the spellbinding costumery of Gabriele Binder. And then there’s Anya Taylor-Joy, playing our brooding hero, the wunderkind chess player Beth Harmon. Those enormous anime eyes of hers are a sight to behold—and fascinating fodder for a blog post about the relationship between games and literature!

It’s a timely story, too. The Queen’s Gambit is about a woman who plays games, plays them brilliantly, and plays them despite the skeptics and hapless helpmeets who surround her—almost all of them men, more than a few enthusiastically sexist. It’s the kind of story that our culture needs now—a reminder of how women have been and are treated in game culture, and an inspiration for girls and women to play more. I particularly liked the relationship between Beth and her mother, played brilliantly by Marielle Heller. Despite her own troubles, she supports Beth unconditionally and affirms her desire to play. Finally, the series is a perfect example of what I call “Playful Literature”: a story about a game, a game player, and a game culture, told with a playfulness of tone and structure that rhymes with the game it portrays.

An old-fashioned story

That said, it’s all rather old-fashioned. And I don’t mean the clothing, furniture, and music of mid-century modernity. The Queen’s Gambit is an old-fashioned fairy tale. Beth is an archetypal orphan who discovers magical powers, a key to the castle, and a host of helpers and hindrances on her path to glory. It’s an old-fashioned sports movie, too. We’ve seen this plucky, obsessive, troubled underdog in countless films, from the mythic The Natural (1984) to the gritty The Wrestler (2008) to the adorable Bend It Like Beckham (2002). And it’s an old-fashioned chess movie, too, sharing with both fictional and documentary films a fascination with children who play and the costs the best players must pay to win: Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993), The Luzhin Defense (2000), Brooklyn Castle (2012), Pawn Sacrifice (2014), Queen of Katwe (2016). Like these, The Queen’s Gambit centers its story in the dramatic sweet spot among the formal beauty of chess’s rules, its arcane rituals, and the disorder and pain of life outside the sixty-four squares of the board.

However, unlike the tortured souls in The Luzhin Defense and Pawn Sacrifice, The Queen’s Gambit treats all that ugliness with the lightest of touches. As historical as it might seem, the facts of the matter tell us that Beth would have been treated far more cruelly by the players and institutions of chess. In 1963, grandmaster Bobby Fischer told an interviewer, “They’re terrible chess players . . . I guess they’re just not so smart . . . I don’t think they should mess into intellectual affairs, they should keep strictly to the home.” While Fischer’s misogyny may have been exceptional in its virulence, his peers (including Grandmasters Nigel Short and Garry Kasparov, the latter a consultant on the show) have shown little compunction opining on women’s ability to succeed in the sport. Similarly, Beth’s addiction to tranquilizers and booze are treated with rather jaw-dropping glibness–she shakes them off as if they were no more than a perfectly tailored shift dress. But that’s part of the point. The Queen’s Gambit is “happy melodrama,” as Julia Turner put it in a recent Slate Culture Gabfest episode. While it titillates us with the typical tropes of tragedy, the series ends in tear-jerking triumph. Beth leaves the pills and alcohol behind. She overcomes her anxieties to beat the best player in the world. And she magically transforms the sexism of her sport into a scrum of hirsute fanboying Brezhnev-era chess-obsessives.

The Queen’s Gambit as playful literature

But it’s not those bearded boardgamers who fascinate me. It’s Beth’s eyes. Those eyes are a constant motif of the series—and it’s biographical bookends. The last words Beth’s mother says to her are, “Close your eyes.” And Beth’s eyes are the focus of the last image we see before the final series credits, peering at us with coy predatory pleasure and inviting us to play.

And it’s right there, as I stared back into Taylor-Joy’s eyes, that I found myself realizing that the show was a fascinating example of Playful Literature.

As I’ve explained in a previous post (though focusing on videogames) and in a forthcoming article in [Arts] magazine, there are seven tropes that define the genre of Playful Literature. The Queen’s Gambit uses three of them. The first, diegetic representation, is obvious. This is a story about chess, the players who play it, and the culture surrounding it. The second is fairly obvious, too. The series represents games figuratively. Chess is a metaphor. Beth says so quite frankly to an interviewer after she wins her first major tournament: “It was the board I noticed first. It’s an entire world of just 64 squares. I feel safe in it. I can control it; I can dominate it. And it’s predictable, so if I get hurt, I only have myself to blame.” That metaphor circulates in the many moments when the day-to-day chaos and constraints of Beth’s life are contrasted with the stately order of the game and the calm, calculating cognition required of those who would master it.

Which leads to the third trope, which is a bit more difficult to ascertain, but is by far the most fascinating: procedural representation. Procedural adaptation is a formal technique in which a game procedure, mechanic, or “feel” is remediated from one medium to another. Perhaps the most obvious example would be the “respawn” mechanic that we see in Groundhog Day, Edge of Tomorrow, Russian Doll, and Happy Death Day.

It’s on the level of procedural representation that The Queen’s Gambit reveals not only its curious attitude towards women gamers, but also its own historical character–not how it represents history, but how it figures the tensions and contradictions of our own moment. Beth’s eyes are an immaculately shadowed and mascaraed portal into a kind of political unconscious of recent gaming history—specifically, the history of men thinking about and watching women play games and the particular ways that playing games plays games with that watching. Which takes us to the question of “the gaze.”

The gaming gaze

In feminist theory, there is a concept known as “the male gaze.” Simply put, the male gaze describes the way art, literature, and culture constructs women as objects of visual pleasure for men. This is particularly evident in movies. In her classic 1973 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Laura Mulvey describes how classic Hollywood films both visually objectify women and construct differential agency for the men and women in them. Not only are women sexualized, but are denied the ability to take action. It’s not just the way they’re looked at by the viewer, but also the way they’re looked at by the men in the movie. Women are objectified by both camera and character. The “cinematic gaze” eroticizes women and film itself.

The Queen’s Gambit tells the story of how Beth Harmon discovers, masters, and reverses the male gaze. The story begins in an all-girls orphanage run by women. This is significant. The two men who work there are functionaries, and neither of them looks at the girls in a way that would suggest sexualization. Though the male gaze is absent in the Methuen Home, the disciplinary gaze is not. Beth and the other girls are under constant surveillance. But Beth’s friend Jolene teaches her how to sneak about, avoiding the eyes of head-mistress and orderly alike to get high and play chess.

It’s when Beth is adopted that she learns what it is to be looked at as a woman by men. Though she embraces fashion, recognizing the power of glamor, she refuses to play the reindeer games of alpha-mean-girl Margaret and her Apple Pi club, all of them intent on looking beautiful to men. Yes, the producers of the show can’t resist lingering over Beth’s body at times, most gratuitously when Beth surrenders to drugs, drink, and rock ‘n’ roll and dances in her underwear. And Beth herself learns to manipulate the male gaze–and the limits of that ability: she fails to recognize that Townes is gay, and is stung when Benny informs her that sex is out of the question.

But the male gaze is not the only gaze in play in The Queen’s Gambit.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how the gaze works in tabletop games and tabletop game culture. Players of card games, board games, paper-and-pencil games, dice games, and so on know that the eyes play a key role. They are a primary source of information. We look to see where tokens are placed and calculate their advantages and disadvantages. We look to identify our cards, the cards on the table, the cards we can see and not see. We look to see the spaces on the board and calculate their offensive and defensive possibilities. The gaming gaze is an informative and calculative gaze.

But there is another dimension to the gaming gaze, which involves desire and excitement. This is most evident in Poker, a game of secrecy and deception. The moment-to-moment labor of Poker involves calculation, of course: the odds that a player has a specific combination of cards or might acquire a specific card from a draw, and so on. But the real fun—and the delicious dramatic tension—of Poker is in watching the other player’s performances and crafting one’s own, in playing a daring bluff, detecting an opponent’s tell, keeping one’s cool when a turn of cards goes one’s way or doesn’t. Yes, the “gaming gaze” is every bit as objectifying as the male gaze, but its energies tend to be directed towards purely strategic ends and is understood by the players to be a fair and legal part of the game. Does the gaming gaze lack erotic charge? Certainly not. Even a casual perusal of movies featuring high-stakes card games demonstrates quite the opposite. The gaming gaze provides the perfect fodder for dramatic storytelling. There is a kind of “eroticism” to the gaming gaze in that it involves desire, seduction, satisfaction, and denial.

Which is what makes the chess matches in The Queen’s Gambit so glorious! The cinematic and dramatic tension of these sequences is generated entirely by watching players watch and seeing what they’re watching. We see it again and again: the camera lingering on their eyes, then shifting into rapid shot-reverse-shot sequences that show them calculating possibilities of play.

But the gaming gaze in The Queen’s Gambit is inseparable from the male gaze—both the gazing eyes of the men in the series and our own eyes as we watch Beth and watch her being watched. The sexism of chess culture isn’t just shown in the disrespect of the men, but the way they look at Beth. This is true of many gaming cultures; most notoriously, videogame culture, where sexual harassment remains a widespread problem and sexist tropes continue to be used by designers. However, The Queen’s Gambit takes pains to distinguish the gaming gaze from the male gaze. This is perhaps most evident when Beth schools a young Russian chess prodigy, countering his sexist microaggressions by drawing his gaze away from the board and towards her, causing his attention to fail and costing him the match.

The extrication of the gaming gaze is most visually fascinating when it comes to the series’ most enduring image: Beth staring at the ceiling and seeing a chess board, pieces moving magically at her mental command.

Indeed, that hallucinatory chessboard is the subject of its own heroic subplot. Isolated and frightened at Methuen Home, seeing a chess board provides her comfort and agency. Isolated and unsure when she joins her adopted family, she tears the canopy of her four-poster bed so she can see the ceiling.

And her victory over her nemesis Borgov follows the moment she is able to invoke the imaginary chessboard in public, without the aid of drugs, without concern for others. Not coincidentally, this is the moment when the men in the room stop looking at Beth, when they follow her gaze, when they seek to see what she sees.

But, of course, they cannot. Which is why the conclusion of the series—with that undulating scum of bearded gamers and that final, seductive invitation from Beth’s eyes and voice—is perfect.

And perfectly problematic. For at that moment, the camera positions us as both player (gazing at Beth from the position of the unnamed, greybeard from an all-male chess community) and viewer. Beth returns that gaze. But is the gaze she’s returning fully divorced from the male gaze? I’d argue that it doesn’t. Anya Taylor-Joy’s eyes and lips and perfect skin are as gorgeous and as perfectly eroticized as they’ve been throughout the series. The typical conventions of female beauty remain in play. But perhaps there is a different kind of eroticism informing our gaze at this moment, a more egalitarian kind of eroticism, the eroticism of fair play. Which I’m kind of into, and think we all ought to try.