December 19, 2018

This is the twelfth in a series of posts dedicated to works of videogame literature and theater—not videogames that are literary or theatrical, but rather novels, plays, television series, graphic novels, museum installations, poems, immersive theater, and movies that represent in some fashion or another videogames, videogame players, and videogame culture. For a general description of my critical framework and purposes, see the first post in the series, “What is videogame literature?”

(Spoilers)

EVENING 7: PLAYING IN MEDIA SPACE, PART 1

What we read:

Bryan Lee O’Malley, Scott Pilgrim Gets It Together

Marie-Laure Ryan, “Tuning the Instruments of a Media-Conscious Narratology”

What we watched:

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (director Edgar Wright)

Drew Morton, “From the Panel to the Frame: Style and Scott Pilgrim”

What we did:

This session marked the third and final part of our exploration of space, videogames, and fiction. We were becoming . . . thoroughly . . . spaced . . . out.

Moving on.

A quick review: in the first part of the unit, we approached space with the idea that it was fundamental to videogame fictions. When videogames tell stories, they tell them in and with space. Space is to videogames what words are to poetry. For our second evening LINK, we explored the spaces around videogames: family rooms, arcades, live streams, and arenas. We played games and read fiction and theory that explored the ways that videogames, interpersonal relationships, and our bodies are intertwined.

Thus, having thought about (1) games as spatial fictions and (2) play as an activity that always occurs in space, it was time to turn to the question of media; specifically, media as a space of play.

What do I mean by media as a space of play? Visit your local videogame store and what do you see? In addition to videogames, consoles, controllers, headsets, and the like, you’ll probably find t-shirts and mugs, mini-figures, replica weapons, special editions of Monopoly and Risk, posters, stickers. This isn’t just clever cross-marketing. These objects imaginatively extend the space of a game’s fiction from in-game to in-world. Here, we see all kinds of ways for us to play with different media.

In other words, we see in such stores the ways that play is distributed across media.

This kind of distributed play is increasingly typical of videogames. Consider Overwatch. While I rocket around in my hot-pink mech suit, I can participate in the live in-game chat, trading tactical information, talking trash, or just gossiping with my teammates. When I’m not shooting other avatars in the face (or, better yet, booping them into Deadlock Gorge), I can dance, gesture, affix graffiti-like stamps to apply to walls and floors, and shout catch phrases, allowing me to play with others in non-violent, often humorous ways. There are whole subcultures surrounding these affordances. There are legends of a small, but passionate BDSM community that has repurposed Overwatch avatars and emotes so they can “get their dom off” while playing a “healslut.” In sum, I can choose how I play the game, distributing my performance across the various in-game media and affordances.

I can distribute my play of Overwatch in ways that don’t involve a controller or headset. I can browse Blizzard’s official website, keeping up with changes in the game’s mechanics and avatars, reading digital comics and watching videos about my favorite characters (D.Va and Lucio, of course), getting news about upcoming in-game and in-real-life events, and communicating with other Overwatch fans. I might visit fan-run sites to discuss strategy and tactics or check out fan-produced fiction and art, machinima, or cosplay. I might tune into the latest match between the Guangzhou Charge and the Paris Eternal, two of the professional teams vying for this year’s world championship and the $1 million prize that comes with it. I can log onto my favorite Reddit forum to participate in the vibrant LGBTQ+ Overwatch community. For sure, this isn’t “playing a videogame” in the strict sense, but it is definitely playful, and for someone who’s interested in the relationship of videogames and literature, this kind of mediated activity is profoundly interesting.

In fact, I’d argue that the emergence of distributed play is far more significant to the history of videogames than the growth of computational power.

Henry Jenkins has a name for this kind of distributed, playful storytelling: convergence culture. As he describes it, convergence culture is a phenomenon in which content circulates “across different media systems, competing media economies, and national borders” (3). What makes it specifically playful is that the circulation of content “depends heavily on consumers’ active participation” (3). Jenkins argues that convergence culture isn’t just a shift in the technology of media circulation and consumption, but a full-fledged “cultural shift” in which “consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections among dispersed media content” (3).

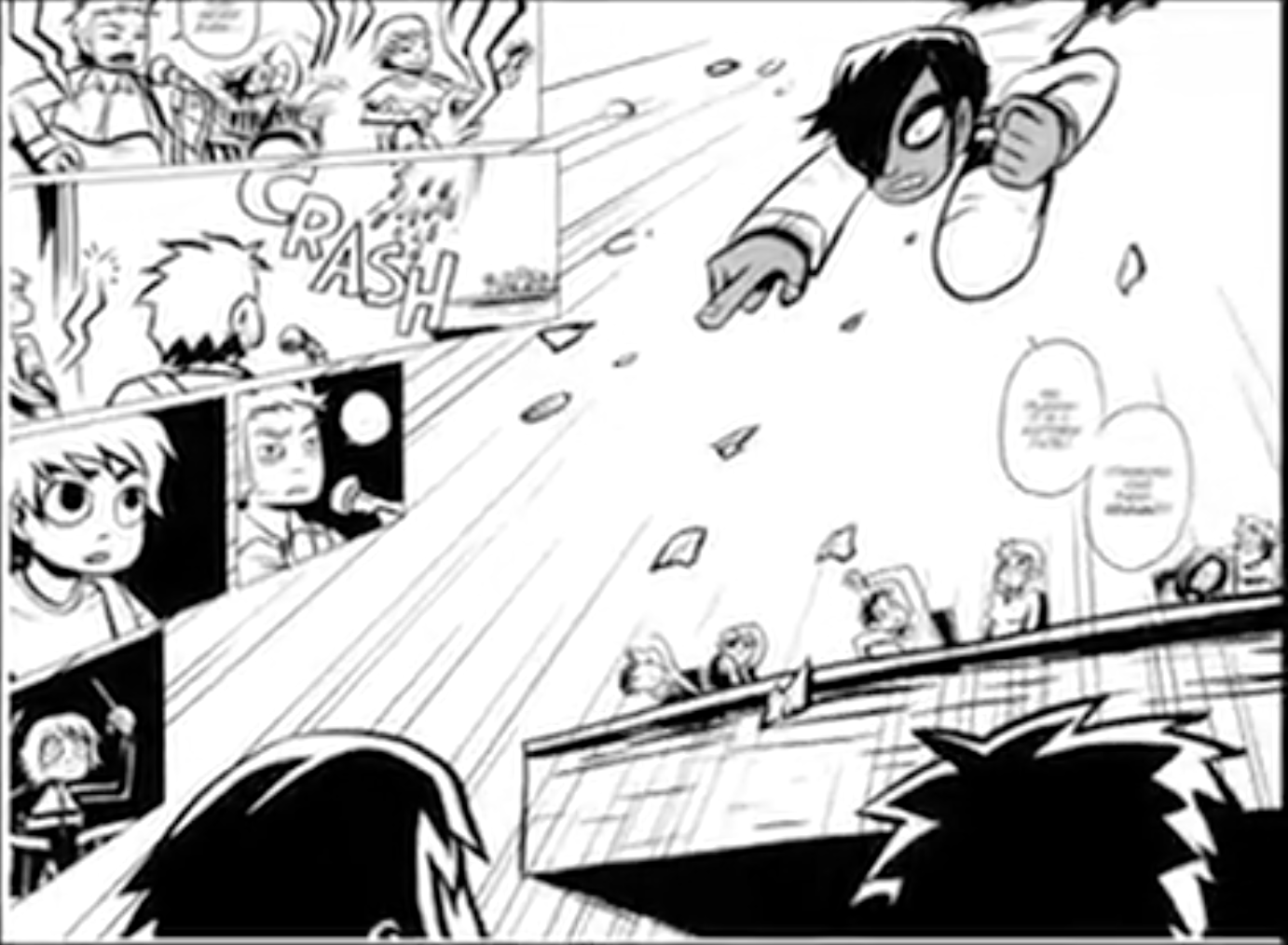

A perfect illustration of convergence culture and the kinds of stories that can be told in it is the Scott Pilgrim franchise. We took a close look at the fourth volume of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s multi-volume graphic novel. I chose that volume because it shows Scott finally coming to terms with his actions and it fleshes out the character of Roxie and her relationship with Ramona. We watched Edgar Wright’s film Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (which flattens Roxie and her relationship with Ramona). And we took a look at a couple of YouTube videos of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World: The Game (we couldn’t figure out how to access the game itself).

Our first guide through the twists and turns of this tale of transmedia storytelling was Drew Morton, who’s video “From the Panel to the Frame: Style and Scott Pilgrim” is wicked smart and you should watch it as soon as you have a moment. (And you should check out his book, too!)

There are two takeaways from Morton’s video. First, transmedia storytelling is an historical phenomenon, the consequence of tectonic shifts in the structure of the media market; specifically, the rise of super-massive media conglomerates like Viacom-Paramount (1994), Disney-ABC (1995), and NBC-Universal (2004). At the time he produced his video (2012), TimeWarner (now WarnerMedia), owned HBO, Turner Broadcasting, CNN, Warner Bros., WB Interactive, DC Comics, and Time Magazine. This helps explain why The Matrix franchise was marketed across so many media: feature films, animated shorts, DVDs, websites, videogames, web, comics, and books. TimeWarner saw an opportunity to make a lot of money by making a lot of different Matrix franchise products.

But transmedia storytelling is more than just a marketing strategy.

Which leads to the second takeaway from Morton’s video. Transmedia storytelling reflects the desire of creators like the Wachowskis (creators of The Matrix) to tell stories in new ways, with new tools. Morton argues that the last three decades have seen the emergence of a distinctive “transmedia style.” The most obvious characteristic of this style is “remediation.” Remediation is defined by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin as “the representation of formal or stylistic characteristic(s) commonly attributed to one medium in another.”

The Scott Pilgrim franchise is a perfect example of this transmedia style. The stories told by O’Malley, Wright, and Paul Robertson (lead on the Scott Pilgrim videogame) all feature the same characters, settings, and themes, but also share a repertoire of visual and audio elements, which they borrow from each other and from other texts.

O’Malley’s comic remediates videogames, music, and manga.

Wright’s movie remediates music, videogames, and other movies (I love the Bollywood battle).

And, of course, it also remediates O’Malley’s comic. This makes Wright’s movie “a remediation of a remediation.”

Isn’t this just fan service and product placement? For sure. But that’s not the only driver of transmedia style. As Morton explains, “There’s a different interpretive lens applied with each remediation, as the artist adapts the previous medium into another.” While transmedia style is no doubt a marketing strategy of mega-corporations like Alphabet, Disney, Comcast, and Bertelsmann, it is just as evident in the work of slash fiction writers, cosplayers, and indie game developers like the good folks at Cardboard Computer, the makers of the several texts that we studied during the second night of our unit (and that will be the subject of the next post in this series). In other words, transmedia storytelling is a way to tell different kinds of stories and tell them in new kinds of ways.

Which brings us to a question. Whether a transmedia story is told by a high-power film director or an indie artistic collective, it is still a story. And it is the responsibility of literary critics to engage such stories with empathy, intelligence, and critical acumen. But how can we do that work when the text we’re examining is not one text, but many; not one medium, but several?

Morton helps us think about (1) the historical forces innovating storytelling and (2) the kinds of tools creators and consumers have at their disposal to do that storytelling. But his analysis of transmedia storytelling doesn’t help us when it comes to the close analysis of individual stories. If Wright’s movie applies a different interpretive lens to Scott Pilgrim’s story than O’Malley’s comic or Robertson’s videogame, then how exactly does that change how we experience the characters, themes, conflicts, settings, point of view, and tone?

Let’s take a closer look at the differences between the movie and the comic. Both represent the post-adolescent, self-absorbed, pathologically carefree, decidedly male worldview of Scott Pilgrim. Both of them make clear that Scott’s choice to live life as if it were a videogame is a symptom of his immaturity and irresponsibility. But where O’Malley’s comic lays out the causes and effects of that worldview and shows Scott and his friends coming to terms with it, Wright leans into it and makes Scott’s pilgrimage a classic boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl, boy-wins-girl thing.

This isn’t just a matter of authorial choice. The differences are driven in part by the media. The manic editing, countless Easter Eggs (well, actually, someone did count them), relentlessly witty visual and audio effects, and verbal derring-do of Wright’s movie makes it a lot of fun. But there’s a contradiction to Wright’s telling of the tale that discomfits me. I can’t decide if Wright is satirizing the gamerboy attitude or serving it. Honestly, it feels like he’s doing both, trying to have his cake and lie about it, too (Portal reference there).

Contradictions aren’t necessarily a bad thing. The contradiction between a text’s form and content can be a source of humor, irony, and insight. But I don’t see that in Wright’s movie. I don’t see critical irony in the two-dimensional female characters or the way those characters serve as little more than a vehicle for Scott’s journey. This is not the case with O’Malley’s comic, which is as visually and verbally inventive as Wright’s movie. However, there’s something about the comic book medium—its two-dimensionality, its lack of sound, its inherently fragmentary structure, the tension between word and image, the particular reading practice it requires from us—that sharpens the satirical edge.

So, while understanding the historical causes and formal characteristics of transmedia style is vital to thinking about transmedia storytelling, it isn’t as useful when we want to dig into plot, character, conflict, setting, point of view, tone, and so on.

To further sharpen our thinking about transmedia storytelling as literature, the students and I relied on Marie-Laure Ryan, a maven in the field of media-centered narrative studies. In “Story/Worlds/Media: Tuning the Instruments of a Media-Conscious Narratology,” Ryan asks, How are stories shaped by the medium through which they are told? We know that “the choice of a medium makes a difference as to what stories can be told, how they are told, and why they are told” (25). What is that difference?

Ryan suggests we think in terms of three registers of analysis: semiotic substance, technical dimension, and cultural dimension.

The semiotic substance of a medium is, simply put, its sensorial aspects: image, sound, language, and movement, for example (29). The Scott Pilgrim comics use words and images to tell the tale. The movie uses words, images, and sound. The videogame uses images, movement, sound, and haptics.

The technical dimension of media helps us to tell one medium apart from another in terms of “media-defining technologies . . . but also any kind of mode of production and material support” (29). Drew Morton describes a moment in the Scott Pilgrim production history that illustrates this idea well. When film production began in 2009, O’Malley hadn’t written the ending yet—an ending that would resolve the big question of whether Scott would end up with Ramona or Knives. Wright went ahead and filmed an ending, but test screenings didn’t go well. So, he and O’Malley consulted and went with the ending that we now see in both the comic and the movie. In other words, the demographic and economic forces surrounding film production pressured O’Malley to choose his ending. In Marie-Laure Ryan’s terms, one technical dimension shaped the other.

Finally, the cultural dimension allows us to differentiate media in terms of the “institutions, behaviors, and practices that support them” (30). Videogames are a distinct media form in terms of their semiotic and technical dimensions, of course, but also in terms of the multiple subcultures that surround them. We might think here of the differences between hardcore and casual gamers or RPG players and FPS stans. Or we might think again about the ending of the Scott Pilgrim narrative, an ending that was unacceptable to the audience sought by Universal, but might have been perfectly acceptable to readers of the kinds of comic books that O’Malley writes.

Having identified the three dimensions of media, Ryan describes three methods to analyze them. First, we can take a semiotic approach, which would focus on things like “language, image, sound, movement,” etc. both individually and in combination (30).

Let’s say we wanted to analyze the way diversity is represented in Overwatch. For sure, we’d want to talk about the backstories of the various characters—the fact that they come from different parts of the world and have different ethnicities, genders, sexualities, and species. But we’d also want to talk about how these differences are constructed semiotically: how the African characters are made to sound different from Americans, and how Americans sound different from Australians, and how Australians sound different from Latin Americans. We might talk about how the women are constructed to move differently than the men, how the white characters look different from the non-white characters, and so on.

Second, we could take a technical approach, which focuses on how a given technology “configure[s] the relationship between sender and receiver” or on the specific cognitive demands of a given “material support” (30).

Playing Overwatch on a console is different from from playing on a PC. Playing with a controller tends to be less precise than with a keyboard and mouse, so Blizzard provides console players “aim assist,” which automatically slows down crosshair movement when it scans over an opponent. Turning works differently, too, the console version being significantly slower. Thus, it’s easier to flank your opponents when playing on Xbox or PS4. How does this affect storytelling? On PC, snipers are more dangerous, so characters like Widowmaker are more threatening and, arguably, glamorous. On console, flankers are more dangerous, so characters like Tracer and Reaper enjoy greater status.

Third, we can employ a cultural studies approach and investigate the behaviors of individuals and groups or the formal and informal institutions in which narratives are produced, circulated, and consumed.

There are immediately recognizable differences between the culture of Overwatch on console versus PC. PC players have easier access to audio chat and can also communicate to each other via text, typing on their keyboards. The ease of communication likely contributes to the more toxic atmosphere of PC Overwatch. PC players also have access to game updates in advance of their release on console, allowing them to provide feedback to the game’s developers. As a result, the PC Overwatch community feels more like a traditional “hardcore” community. (Thanks to Psyche at MMOGames.com for breaking these differences down!)

So far, so good. We have the tools to map these “distributed” narratives and analyze each transmedia narrative as a unique conjunction of semiotic signaling, technology, and culture. But we also need to think about the larger structure in which each narrative component of the transmedia story fits. For that, Ryan tells us, we need to think in terms of “storyworlds.”

How do the semiotic, technological, and cultural affordances of a specific medium enable the stories told in that medium to communicate a sense of coherent and consistent reality? How does what we are watching, reading, playing, or hearing create for us the feeling that the story we’re experiencing takes place in a coherent, consistent universe, even when the kind of experience we’re having is as different as a 250-page novel and a shelf full of action figures?

She suggests that storyworlds are composed of the following elements:

- Existents: “the characters of the story and the objects that have special significance for the plot” (34)

- Setting: “a space within which the existents are located” (35)

- Physical laws: “principles that determine what kinds of events can and cannot happen in a given story” (35)

- Social rules and values: “principles that determine the obligations of characters” (35)

- Events: “the causes of the changes of state that happen in the time span framed by the narrative” (36)

- Mental events: “the character’s reactions to perceived or actual states of affairs” (36)

Each storyworld element is constructed and communicated differently, depending on the medium in question. A novel communicates the mental events of a character differently than a movie. A theater performance communicates the social rules and values of its characters differently than a videogame. Each medium has different capacities when it comes to representing the elements. Action figures are pretty lousy at communicating setting. A videogame is really good at communicating physical laws.

A given text will emphasize one or more storyworld element differently than another text. For example, when we play The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, we focus mostly on setting and events. As Link, we explore Hyrule, discovering dungeons, villages, characters, and so on. As we explore, we also learn about events that took place before we awoke from our slumber. And as we explore, we cause events to happen that change the present. In contrast, when we play Link in Super Smash Bros, we focus mostly on the physical laws and social rules and values of the game. We use the specific movement, attack, and defense abilities of Link to attack other characters, evade their attacks, gather resources—all of this in order to win the game.

A given text will construct a different interpretive framework around each storyworld element. For example, in both the comic book and movie version of Scott Pilgrim Vs The World, the crucial storyworld elements are characters, events, and mental events. Both versions construct a storyworld in which a young man embarks on a heroic journey in which he confronts and defeats the former lovers of a woman he desires and, in so doing, grows as a human being and wins the love and respect of that woman. But, as we discussed earlier, the ways that O’Malley and Wright construct these for the reader and spectator, respectively, create a rather different interpretation of Scott’s journey.

Finally, a given text places specific obligations on and fulfills specific expectations of those who read, watch, or play it. In other words, a given text requires different kinds of cognitive, imaginative, and physical activity from those who read, watch, or play it.

In sum, Ryan teaches us how to identify the specific media characteristics and storyworld strategies of a given work. This enables us to do valuable kinds of comparison-and-contrast analysis with the transmedia text. This not only allows us to get a better sense of how the text constructs its storyworld, but also what it asks us, as readers, spectators, and players, to do (42).

Having reached the end of our evening, it was time to rev up our engines, check the map, and get on our way to Kentucky Route Zero, which is the subject of the next post in this series.