Pedagogical Intervention 2: Edmodo: Educational Facebook

Edmodo is built for educators and students by educators and students. This digital sharing forum functions as more of a social Moodle/Blackboard-type site, but greater focus on qualities of those similar to microblogs and social networking sites. The biggest thing that caught my attention when exploring the site was its uncanny resemblance to the Facebook layout, which, I am sure, was no accident. Though I could find no philosophy statement rationalizing the layout of the site as rooted in the social aspect of academia, the proof is in the pudding. (I think I used that term correctly. I’m still never sure after Bernstein.)

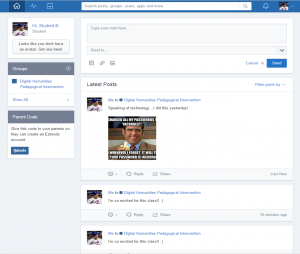

This is the general view of Edmodo when opening a student home page, which is extremely similar to one’s Facebook home page:

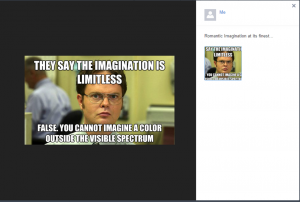

Additionally, when one posts a picture, the visual layout is also the same:

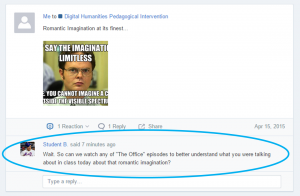

One can also comment on a photograph or post in the same fashion that a Facebook user is able to:

After looking more deeply into the site’s constructs, its collection of mission statements refer to this site as K-12, availability for entire school districts, and emphasis on Common Core educational standards and a variety of networking between teachers and teams to share curriculum. However, I think that this would be a great tool for undergraduates, who are still in the transition between 12th grade and Freshman-level coursework. This site location provides a low-risk environment that capitalizes on an architecture that so many students are already familiar with (Facebook). However, the framework is redesigned and reimagined into an educational context, thus forcing the collaboration between social and academic. This makes the transition from social network to a sociable scholarly network—the point of college.

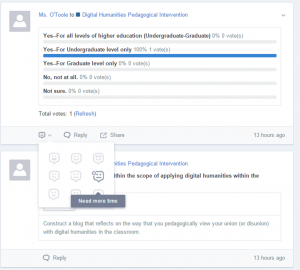

One way that this site endeavors to shift the sociable aspect of Facebook to the academic sense is the functions of posts. On Facebook, you are able to “Like” and “Comment.” With Edmodo, you have the ability to “React.” There is an option where you can “Reply,” “Share,” or “React,” with any of the following emoticons in a drop-down list: Awesome!; Like it!; Interesting!; Tough/Challenging; Not taught in class; Need more time; Bored; Need help; Lost interest

Further similarities between Facebook and Edmodo can be visually noted throughout the other screenshots offered in this post.

For this intervention, I created a teacher account and a student account so that I could see how the site functions from both ends.

Edmodo is free, but does have options to upgrade for larger spaces. With the teacher account, you have the ability to create different groups (classes), where each page functions as a different class page. There is a library, similar to the “Content” section of d2l or Moodle, which provides a space for uploaded files. For students to join your page, all they need to do is sign up with a username and have your access code. Feel free to join my test page to try it out for yourself: Go to Edmodo.com, fill in the needed information and use the code: dfys3d (Post, take the quizzes, etc.—you are most welcome to anything. I suggest you take the expert quiz. Dr. Sherwood may make an appearance in one of the questions.)

Assignments

There is the option to create assignments, quizzes (matching, multiple choice, fill in the blank, short answer), and polls. (I have one of each created on my site if you’d like to check it out.)

Students can also upload their own documents to this site, similar to a Dropbox for assignments or an online submission. There is also a library for students to see what they have submitted, so that things can’t “magically disappear.”

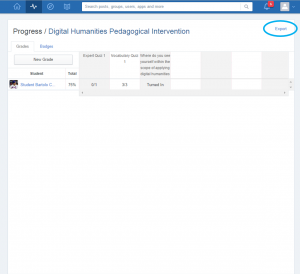

Grades:

Grades for the assignments are taken care of for you. All grades are calculated and made into a table on the site. There is also an option to export the grades to an Excel file. You can adjust the point value and the time permitted to take each test and assignment when creating the type of assignment, as well.

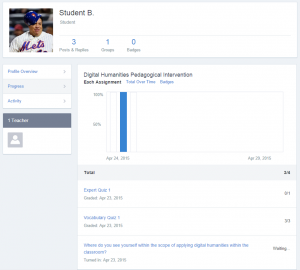

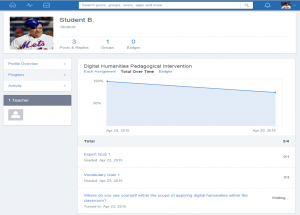

Students also have the ability to view their progress throughout the course, as it is all tracked through Edmodo. There are two visualizations that are available when viewing their progress. The bar graph shows the completion of the assignments, while the line graph shows the quality/actual grade of those completed assignments.

The poll that I created was would this be an effective classroom tool for classrooms in higher education? My response: I’m not sure. As I stated earlier, I could certainly see something like Edmodo holding promise in a Freshman course. But, the tool is limited by its use for the classroom–just as Moodle, Blackboard, etc. I’m not sure how long this material is available online, or if students have forever access to this site. No information is available for that. I’m guessing with only so much space, with a teacher account, it is only a matter of time before I have to delete a group and all of its contents, including its pages and all student work, posts, pictures, files, etc. So, I’m not sure of the viability that this would have. But, I’m also not sure if it is the viability or the longevity that is the point of using DH in the classroom and beyond the classroom. And, we’ve talked about this before. With having DH in university standards, but no clear objectives to advocate those standards, it is difficult to understand what that means within the confines of our own classrooms, and even our own pedagogies. If using DH in the classroom means using a tool that get students genuinely involved, then I think Edmodo could do that for incoming Freshman. Beyond that, I’m not so sure.