Happy Labor Day! I hope everyone, especially the archaeologists out there, are getting plenty of rest today! My name is Bridget Roddy, and I am the new Public Archaeology Graduate Assistant. I am starting my first year in the graduate program for Applied Archaeology here at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. I completed my undergrad degree in 2020 from Ohio Wesleyan University, double majoring in Sociology/Anthropology and Psychology and minoring in International Studies. During my time there I received a grant to travel to Romania for a month for an archaeological excavation at the Roman fort of Halmyris. This strengthened my interest in archaeology, leading me here to IUP’s Master’s Program. I participated in the Newport Field School this summer, as well. My other interests and hobbies include, running, art, reading, photography, and traveling. I am excited to get started and if anyone has any questions or concerns about the blog, or if you are interested in submitting something to this page, please feel free to reach out to me through my email bzxcc@iup.edu!

Gage Huey Thesis: Social Zooarchaeology At the Philo II Village

Written by Gage Huey

Zooarchaeology, or the study of animal remains in archaeological contexts has addressed the utilitarian aspects of human-animal interaction through decades of research on nutrition, seasonality, domestication, and the various techniques of carcass procurement and processing used by hunting cultures across the globe. As a result, traditional zooarchaeological interpretations rarely address the non-utilitarian meaningfulness of animals to the peoples whose material cultures we study. The way that archaeologists tend to think about human and animal relationships in the past typically reflects the structures and assumptions from our own worldview. These assumptions situate animals as an Other to humans, they serve our needs and can be used by humans but are fundamentally a different Thing. Over the centuries, these constructed differences between human beings and nature became more naturalized, fitting seamlessly into the colonial worldview that characterizes our “modern world”. Because scientific paradigms like anthropology were constructed within this worldview and the structures it produces. The interpretations we make as scientists reflect these as well. I believe this has led to misinterpretation of animal bones present at precontact sites through a largely Western perspective.

Zooarchaeology, or the study of animal remains in archaeological contexts has addressed the utilitarian aspects of human-animal interaction through decades of research on nutrition, seasonality, domestication, and the various techniques of carcass procurement and processing used by hunting cultures across the globe. As a result, traditional zooarchaeological interpretations rarely address the non-utilitarian meaningfulness of animals to the peoples whose material cultures we study. The way that archaeologists tend to think about human and animal relationships in the past typically reflects the structures and assumptions from our own worldview. These assumptions situate animals as an Other to humans, they serve our needs and can be used by humans but are fundamentally a different Thing. Over the centuries, these constructed differences between human beings and nature became more naturalized, fitting seamlessly into the colonial worldview that characterizes our “modern world”. Because scientific paradigms like anthropology were constructed within this worldview and the structures it produces. The interpretations we make as scientists reflect these as well. I believe this has led to misinterpretation of animal bones present at precontact sites through a largely Western perspective.

Indigenous peoples across the world (and specifically here on Turtle Island) see and saw the natural world in ways that would be incompatible with traditional zooarchaeological interpretation. So, my thesis research engages with an assemblage of animal remains through a perspective that acknowledges that prior to the arrival of Europeans (and continuing until today), Native peoples engaged with the environment not in terms of utilization, but in terms of relationships. The assemblage I’ve analyzed is from the 13th century (c.700 BP) Fort Ancient village,

Philo II (33MU76) located in Gaysport, Ohio. This village was constructed alongside an especially nice stretch of the Muskingum River known as the Philo Bottoms. This floodplain was home to Indigenous Ohioans for centuries, evidenced by the mound complex on the ridge overlooking

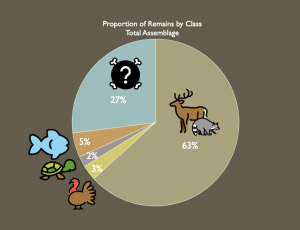

Philo II. These folks would’ve made pottery out of clay and mussel shells collected from the river, shared their pit-houses with dogs and stored maize, and hunted a variety of animals. The bones of these animals frequently ended up in subterranean “storage pits”, and vary in their number, species, and bone type (element) from feature to feature. Within the 55 features I analyzed, 27% of the bones were so fragmented they could only be reliably identified as indeterminate vertebrate. The remainder of the bones were identified to species when possible, but were broadly 63% mammal, 3% bird, 2% reptile, and 5% fish. The Philo Peoples would have had stories, songs, and all manner of cultural practices that engaged with these creatures not as animals in the Western sense, but as non-human persons that participated in society just as the humans did.

These relationships likely were not thought of in

an allegorical or metaphorical sense, they were a historical, lived reality. Imagine that a great ceremony was to be held in the plaza of Philo II, and the ceremony required music. The turtles whose shells were harvested to make instruments for the ceremony were taking part in the ceremony itself. In one sense, they were there (i.e., the turtles were plentiful) because they wanted to be there. And because the turtles had graciously attended the feast, there were particular cultural practices to ensure that they were honored and would continue to engage with the people in this way.

an allegorical or metaphorical sense, they were a historical, lived reality. Imagine that a great ceremony was to be held in the plaza of Philo II, and the ceremony required music. The turtles whose shells were harvested to make instruments for the ceremony were taking part in the ceremony itself. In one sense, they were there (i.e., the turtles were plentiful) because they wanted to be there. And because the turtles had graciously attended the feast, there were particular cultural practices to ensure that they were honored and would continue to engage with the people in this way.

Through my research, I am arguing that the pit features at Philo II are physical manifestations of the intersocial relationships between humans and non-human animal persons. The construction of these features would have disposed of animal bone and provided a means of constructing and naturalizing the relationships present between the Philo Peoples and the animals in which they shared an environment. They may also have connections to cultural practices of memory-making, linking them to their Late Woodland ancestors who moved great amounts of earth to combine bones, sediments, and artifacts into highly meaningful spaces. If zooarchaeologists acknowledge and engage with Indigenous scholars and the perspectives they bring to the field, it would provide an opportunity for old collections to be re-interpreted and analyzed in a new light that more accurately reflects the cultural context of the peoples whose cultures we study.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Jamie Kouba Thesis: Bringing Archaeology into the 3-Dimesional Age

Written by Jamie Kouba

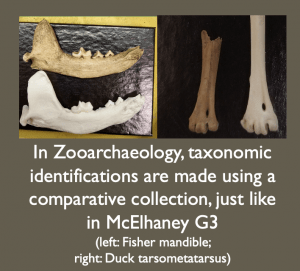

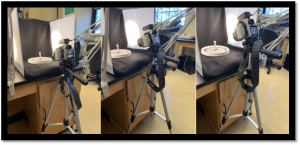

The most daunting part of earning your master’s degree has got to be picking a thesis topic. After a year of anxiety-inducing ideas coming and going, I was talking to a second-year graduate student about technological advances in archaeology and something finally clicked. As it turns out, there is a real need to establish digital repositories of 3D osteology comparative collections of both human and non-human specimens for researchers. Digital comparative collections are a valuable resource for

Jamie taking photographs of a bone to make her 3D model

zooarchaeologists, bioarcheologists, osteologists, and non-specialists alike. When a bone is recovered in the field, there are several questions that must be addressed immediately. First, is it bone? Second, is it human or animal. Typically, a bone specialist is called in to make identifications, or someone accesses a physical comparative collection and hopefully identifies the unknown element. However, an expert is not always available, and physical collections take up a lot of space, money, and time to maintain, limiting access to them. One of the ways to supplement those issues is to reference a digital collection. There are numerous websites out there, including Bone ID, Idaho Virtual Museum, and Sketchfab. Different websites use different formats for how they display their specimens. For instance, Bone ID provides 2D images, and Idaho Virtual Museum provides 3D scans, and Sketchfab is loaded with photogrammetric 3D models. This thesis was born out of one question: are all of these digital references equal in their ability to provide identifications?

While doing research, I found that there was a lot of information on 2D references and 3D scanned references, but very little on the use of photogrammetry to create 3D models. I had a feeling that 3D photogrammetric models would be the most effective form of digital reference. Photogrammetry uses a

The photogrammetry set up

series of photos to create photo-realistic 3D models. An object is set on a rotating platform, and photos are taken all the way around it, from 3 different heights, then the object is rotated 180 degrees and the process is repeated. This technique allows for a 360-degree view to create a 3D model with. My thesis was designed to answer three research questions based on digital comparative collections: 1) Are photogrammetric 3D models useful in identifying osseous materials? 2) Can 3D models provide a more accurate identification than 2D photo references for osteological comparison? 3) Can 3D digital comparative specimens be used to supplement physical specimens that are not available?

In order to answer these questions, my thesis had several parts. The first thing that I did was to create my own digital repository by creating 3D models using photogrammetry. I made twenty models from the bones of bear, pig, cow, and human bone clones. I also made a second digital repository of 2D images of those same bones. Next, I designed a Qualtrics survey to test the efficacy of 2D/3D references. I surveyed 20 people, half received 2D references, half received 3D references. I would have preferred a larger sample, but the Covid-19 pandemic made it difficult to conduct these in person tests on a large scale. When the surveys were finished, I ran a statistical analysis to see how effective each reference was in aiding faunal identification. Along with the photogrammetry and survey parts of my thesis, I also analyzed a 3,600-element sample of faunal remains from Pocky Shell Ring in South Carolina. I made notes during my identifications as to whether I used digital collections or physical collections to assist in making my identifications.

A 3D model created by Jamie

Upon starting this thesis, I assumed that the results of 2D references versus that of 3D photogrammetric references would be vastly different. What I discovered is that there are a lot of factors that can go into determining whether these references are effective. These include the size and completeness of the element itself, whether the desired identification is of bone type, species, or which side it came from. All of my participants reported to having less than five years of experience identifying bones, so none of them were experts. Overall people performed better on identifying bone type on a pig tibia, than they did on a bear metacarpal. Yet those same people preformed much better on identifying that the metacarpal was from a bear, than that the tibia was from a pig. What I can say for sure is that it appears that 3D photogrammetric references, on average, work as well as 2D references, with only about a 10% difference between them. As for my own faunal analysis, I determined that when there are appropriate digital resources available, they are effective in helping to make the correct identification. At the end of this, I feel that although more research is needed to confirm my results, photogrammetry can be used to create 3D digital references collections, which can be used to effectively identify unknown faunal remains.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Savannah Weaver Thesis: Investigation of the Brush Valley Lutheran Church Cemetery using Headstone and Geophysical Analysis

Written by Savannah Weaver

For my thesis project I will be surveying the Brush Valley Lutheran Church Cemetery in Indiana County, Pennsylvania. The Brush Valley Lutheran Church (BVLC) established the cemetery in the mid-19th century shortly after establishing the church. The BVLC property was privately owned by the church until the late 20th century. While the Lutheran congregation still rents the property for services, the cemetery is now used by the community as well as the congregation. The main goal of this thesis project is to analyze notable changes in headstone and burial patterns by comparing the privately owned section of the cemetery to the more publicly used section. Using geophysical methods and headstone analysis, surveys will be conducted over select areas within both sections of the cemetery. Comparative analysis based on the results from these surveys will indicate cultural and historical changes within the cemetery. Secondary goals of the project will be to determine if unmarked burials are present within the selected areas and if the headstones align with their designated burials. Few studies use headstone analysis and geophysical methods together when studying cemeteries. Most researchers use one method or the other. Integrating these two methods allows for more unique data and better interpretations of the cemetery. The results will also provide cultural and historical information about the cemetery and the community it is located in.

For my thesis project I will be surveying the Brush Valley Lutheran Church Cemetery in Indiana County, Pennsylvania. The Brush Valley Lutheran Church (BVLC) established the cemetery in the mid-19th century shortly after establishing the church. The BVLC property was privately owned by the church until the late 20th century. While the Lutheran congregation still rents the property for services, the cemetery is now used by the community as well as the congregation. The main goal of this thesis project is to analyze notable changes in headstone and burial patterns by comparing the privately owned section of the cemetery to the more publicly used section. Using geophysical methods and headstone analysis, surveys will be conducted over select areas within both sections of the cemetery. Comparative analysis based on the results from these surveys will indicate cultural and historical changes within the cemetery. Secondary goals of the project will be to determine if unmarked burials are present within the selected areas and if the headstones align with their designated burials. Few studies use headstone analysis and geophysical methods together when studying cemeteries. Most researchers use one method or the other. Integrating these two methods allows for more unique data and better interpretations of the cemetery. The results will also provide cultural and historical information about the cemetery and the community it is located in.

Headstone analysis and geophysics are the two methods by

which surveys of the cemetery will be conducted. Headstone analysis examines the information on the headstone as well as size, shape, and materials used to craft it. This analysis allows researchers to examine the historical and cultural changes within a given community, such regional patterns, racial, economic, and societal influences on the formation of headstones. For this study, photographs of each of the headstones in selected sections of the cemetery will be taken and catalogued. The catalog will include the inscription, symbol, shape, size, and rock materials of each headstone. A Global Positioning System (GPS) unit will be used to capture data points of each photographed headstone and notable features within the cemetery, such as the chapel and fence line. The GPS data will be used to create a map of the cemetery to be compared against the data from the geophysical surveys.

Alongside headstone analysis geophysical methods will also be used because they provide non-invasive  means of collecting data. For this study, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and Electrical Resistivity (ER) will be used. GPR will be able to identify grave shafts because of its ability to detect breaks or voids in the soil. GPR can also reach greater depths in the soil than other near surface geophysical methods as well as indicate size of the anomaly. The other geophysical method being used is ER which measures resistance soil and objects have to an electrical current. Resistance is measured by using electrical probes, spaced at various intervals. The greater the spacing the greater the depth the current will travel. ER can detect features and patterns below the ground surface. It is most successful at indicating stone, brick, cement, and highly compacted soils. Using ArGIS, maps of the GPR and ER data will be compared to each other to determine location of burials (known and unknown), changes in burial patterns, and the relationship between headstones and their designated burials. Changes in burial patterns could include orientation, shape, size, and depth. The use of headstone analysis and both GPR and ER will provide more comprehensive data and better interpretation of the cemetery and the cultural influences it reflects.

means of collecting data. For this study, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and Electrical Resistivity (ER) will be used. GPR will be able to identify grave shafts because of its ability to detect breaks or voids in the soil. GPR can also reach greater depths in the soil than other near surface geophysical methods as well as indicate size of the anomaly. The other geophysical method being used is ER which measures resistance soil and objects have to an electrical current. Resistance is measured by using electrical probes, spaced at various intervals. The greater the spacing the greater the depth the current will travel. ER can detect features and patterns below the ground surface. It is most successful at indicating stone, brick, cement, and highly compacted soils. Using ArGIS, maps of the GPR and ER data will be compared to each other to determine location of burials (known and unknown), changes in burial patterns, and the relationship between headstones and their designated burials. Changes in burial patterns could include orientation, shape, size, and depth. The use of headstone analysis and both GPR and ER will provide more comprehensive data and better interpretation of the cemetery and the cultural influences it reflects.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Is it a Boy or a Girl? The Binary Issue

A binary system is one which has two answers: 0 or 1, yes or no, female or male. In western cultures sex and gender are of ten considered binary. This is not accurate. Before going into the nonbinary systems that exist in both sex and gender, it is important to differentiate between the two. Sex is the genetic identity that is based on chromosome. The most common categories for sex are male (XY) and female (XX) and traditionally it is accepted that sex is binary. Gender is the socially constructed roles that people are expected to follow. In western cultures like our own, these are feminine and masculine or girl or boy. They are generally based on our sex (or how our sex is presented physically) and we are trained from birth to follow those roles. Baby boys are represented by blue and are given trucks, dinosaurs, and action figures to play with. Girls are represented by pink and given make-up, domestic themed toys, and dolls to play with. In fact, when someone has a child, the first question is often is it a boy or a girl? There are large social impacts that this binary system has on people but that is for a different discussion. This post will focus on the forensic and archaeological implications of assuming binary when examining skeletal remains.

This task force aims to solve cold cases that contain trans or nonbinary individual (http://transdoetaskforce.org/)

In a survey conducted this year on forensic anthropologists showed that 30% of them had handled transgender cases and 42% considered sex binary (TRANScending Jane and John Doe). The problem with considering sex to be binary is that it ignores the 2% of people who are intersex which occurs when an individual has a different chromosomal pattern than XY or XX such as

Intersex flag (https://pridenation.lgbt/)

XO or XXX. The forensics and medical system consider intersex as a pathology or non-normal condition. This designation is problematic because it puts that sex on the backburner. Pretty much all studies regarding sex estimation do not even consider intersex to be a category. 2% of the population seems pretty small but that is also the percentage of natural redheads which is not considered a pathology but a viable and normal hair color. In a forensic sense, only designating an individual as male or female and not even considering gender, could easily prevent their identification. The Trans Doe Task Force and a few other organizations work on cases (specifically cold cases) that involve individuals who do not conform to our binary system. They attempt to correct gender categorizations in the forensic documentation and aid in the identification and resolution of the case.

The consideration of nonbinary gender and sex extremely important in forensics but also in archaeology. Too often to archaeologists impose their own binary system of gender and gender roles onto past cultures. This assumption of customs severely hinders the accuracy of the interpretation and makes cases of obvious nonbinary burials or lifestyles seem abnormal. Many cultures around the world have more than one gender. In some Native American cultures intersex or nonbinary individuals were considered to have two-spirits and many have specific names and roles for those people. When examining burials, it is important to consider not only the sex characteristics of the skeleton but also the context in which the individuals was buried. And the sex of the skeleton does not always indicate the gender of the individual.

Sex estimation scoring system for the pelvis (Walker 2005)

Sex estimations using skeletal remains are also rather variable and not as binary as one might think. Each trait has varying levels of masculinity and femininity and even the designations consist of male, probable male, indeterminate, probable female, and female. I personally saw some of the contradictions and variations of sex estimations in my thesis collection. Some individuals have crania that were quite gracile (likely indication a female) but the pelvis was quite distinctly masculine. Not all traits examined will agree and that determination does not always indicate their place in society. Gender cannot be determined by the skeleton and in cases of intersex individuals, sex might not even be determinable. Because of the prevalence of nonbinary individuals throughout history, new methods of estimating sex need to consider the possibility of intersex and also gender nonbinary systems when interpreting remains. As well, archaeologists and other researchers need to be aware of their own biases when interpreting gender roles of past cultures.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Sources: TRANScending Jane and John Doe

Geller, Pamela L.

2005 Skeletal Analysis and Theoretical Complications. World Archaeology 37(4): 597-609

Jones, Greyson

2014 Not a Yes or No Questions: Critical Perspectives on Sex and Gender in Forensic Anthropology. MA Thesis. Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminology, University of Windsor, Ontario.

Rachael Smith Thesis: Using XRF to Resolve Commingling of Human Remains

My workspace while conducting XRF analysis

My thesis uses x-ray fluorescence and trace element analysis to determine if it is possible to resolve commingling using the elemental composition of human bones. X-ray fluorescence is a type of non-destructive element identification method that bombards a sample, in this case bone, with high energy x-rays which excite atoms causing them to release energy which is specific to each element. The XRF device measures which elements are detected and at what concentrations in parts per million. Commingling occurs when multiple skeletonized individuals are mixed together in a single assemblage. There are a variety of events that can cause human remains to become commingled. These can include single events such as disasters and mass graves, or over multiple events like a reused burial area. When archaeologists come across these commingled assemblages it can be difficult to get any useful information from it. It is important to attempt to resolve the commingling and identify individuals because more specific research questions can be answered, and it might be possible to return such individuals to their loved ones.

This project focuses on the possibility of using the non-destructive

The XRF at work analyzing a vertebra

XRF to resolves commingling which can then lead to identification of individuals. The remains are from the Arch Street Project which houses the burials that were excavated from the First Baptist Church Cemetery in Philadelphia, PA. To do this, I have three main research questions: is there elemental variation within a bone, is there variation within an individual, and is there variation between individuals. For the within bone variation, I sampled six bones (cranium, humerus, tibia, femur, sacrum, and os coxa) at different locations. I then used RStudio analyses to compare the values for each sample locations for each bone. For the within individual variation, I tested these six bones plus three vertebrae, clavicle, and a rib. The last analysis I conducted compared all these bones between the individuals. For all analyses, I used RStudio which has been an interesting adventure into statistics. The statistics I used included nonparametric statistics, two-way ANOVA, and a multivariate ANOVA known as a MANOVA. The last and overarching analysis I will conduct is a mock commingling which will be used to either prove or disprove my hypothesis that XRF can be used to resolve commingling.

The results that appear when the XRF finishes it analysis. The peaks indicate elements and concentrations

The theory behind this project is that overtime elements such as zinc, iron, and even lead replace the calcium in the hydroxyapatite that makes up the bone. The individual’s metabolism, physiological health, and exposures to chemicals during life can determine the concentrations of each element within the bone. Because each person has different physiologies and different life experiences, I believe the element concentrations within their bones will also be different. The main question is are they different enough to separate individuals. Another problem is that bones vary in density and thus element concentrations based on the location on the bone and the type of bone being sampled. Trabecular bone is porous and less dense than cortical bone which makes up the shaft of long bones. The trabecular bone might have different elemental concentrations but is also much more susceptible to diagenesis or the changes that occur post-burial. Diagenesis can change the elemental concentrations within bone. One particularly common diagenetic contamination is lead which can be introduced into the bone through soil and ground water. There are a lot of factors that can impact the elements within bone. My hope is that this research will be able to identify useful methods for distinguishing individuals in a commingled assemblage and allow the reassociation and identification of those individuals.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

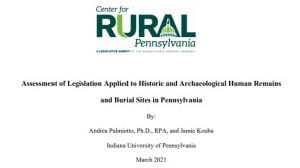

Digging into Human Remains Legislation

Written by Jamie Kouba

“I have a project that I’m working on and I thought you might want to help”. That’s how it all started. Dr. Andrea Palmiotto asked me if I’d be interested in helping her work on a grant funded project. Honestly, I was just excited to help, I probably would have said yes to just about anything. Once I found out what the project was and that it involved archaeology and the law, I was completely sold! Due to the publicity that the

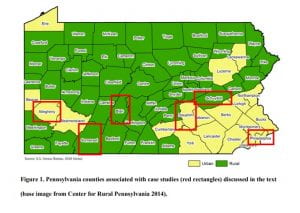

Arch Street Project received for the unexpected discovery of hundreds of human burials, members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly were made aware of certain complicating factors that must be dealt with when human remains are inadvertently discovered. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (CRP) is a bipartisan legislative agency that serves the Pennsylvania General Assembly in helping to create rural policy. In 2019, CRP tasked Dr. Palmiotto with providing a comprehensive assessment of Pennsylvania legislation related to human remains and burials, specifically those of archaeological concern, such as abandoned or forgotten cemeteries, or isolated and unmarked burials. Although there are federal laws regarding the discovery of archaeological remains, those laws only apply to projects that include federal involvement. In the state of Pennsylvania, there is no state-level legislation that adequately addresses the inadvertent discovery of archaeological remains on state owned, state-funded, state-assisted projects, or private property.

Arch Street Project received for the unexpected discovery of hundreds of human burials, members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly were made aware of certain complicating factors that must be dealt with when human remains are inadvertently discovered. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania (CRP) is a bipartisan legislative agency that serves the Pennsylvania General Assembly in helping to create rural policy. In 2019, CRP tasked Dr. Palmiotto with providing a comprehensive assessment of Pennsylvania legislation related to human remains and burials, specifically those of archaeological concern, such as abandoned or forgotten cemeteries, or isolated and unmarked burials. Although there are federal laws regarding the discovery of archaeological remains, those laws only apply to projects that include federal involvement. In the state of Pennsylvania, there is no state-level legislation that adequately addresses the inadvertent discovery of archaeological remains on state owned, state-funded, state-assisted projects, or private property.

After some conversations about what we thought Pennsylvania was missing, in terms of legislation, we ended up with more questions than answers. What is supposed to happen when human remains are discovered? Who is in charge? What happens to those remains after a disinterment? Dr. Palmiotto and

I made a list of agencies in Pennsylvania and other states that we needed to contact in order to gather case studies, and we got to work. Due to the pandemic, we couldn’t meet with any of these agencies in person. Luckily, we had technology and so we did months of research and interviews through emails and Zoom. We gathered dozens of stories, field reports, and news articles and we started to assess which laws were applied to each project and why. As it turned out, because there was only a web of partially intersecting local laws, state laws, and standard operating procedures among different agencies, every case was handled differently. It was really interesting to see how different agencies interpreted that patch work of laws and put them to use. Seeing how each of the projects were handled with the utmost care and respect for the deceased was wonderfully reassuring to my faith that modern archaeology is not grave robbing.

It took about nine months; but at the end of it, we submitted a completed report to CRP that outlined the existing laws and standard operating procedures that are currently being utilized in Pennsylvania and in other states, as well as making recommendations for new legislation that will help to create best practices for the future of archaeological burials. Copies of our report were published by Pennsylvania General Assembly and sent to other state agencies. It is our hope that these recommendations will be used to guide Pennsylvania in the respectful and efficient recovery of human remains. Although Dr. Palmiotto and I didn’t use any trowels, our digging into the Pennsylvania’s laws and regulations regarding archaeological remains will serve the future archaeological record. And for that, I’m so very grateful that I got the chance to work on this project.

The article can be found here: Historic-and-Archaeological-Human-Remains-2021.pdf (palegislature.us)

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

PAC and SPA and You

Image from the Carnegie Blog featuring students and faculty from IUP learning about SPA’s the current rock shelter excavations. (I am in the blue).

IUP faculty and students are actively involved in both the Pennsylvania Archaeological Council (PAC) and the Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology (SPA). This week two members of SPA chapters in the region (Amanda Valko from Allegheny Chapter 1 and Jim Barno of the Westmoreland Archaeological Society Chapter 23) wrote a blog post for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History detailing the reasons for joining these groups and how to get into contact with these two local chapters. PAC is made up of archaeological professions, students, and highly experienced advocational archaeologists. This group “works to advise policy and legislative interests”. SPA is an organization for anyone interested in archaeology and consists of various chapters throughout the state. Their focus in on “promoting the study of archaeological resources in PA, discouraging irresponsible exploration, connecting avocational and professionals, and promoting the conservation of sites, artifacts, and information”. Both organizations do very good work and are great to expanding one’s information and interest in local Pennsylvania archaeology. The link to the full blog is below.

Pennsylvania Archaeology and You – Carnegie Museum of Natural History (carnegiemnh.org)

SPA Chapters: Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology

PAC: Pennsylvania Archaeological Council (pennarchcouncil.org)

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Suffrage and Haudenosaunee

Illustration titled “Haudenosaunee” by Jessica Bogac-Moore. Source: https://www.yesmagazine.org/

This year marks the 100-year anniversary of the 19th Amendment which granted women the right to vote. When we study the women’s suffrage movement, the focus tends to be on the Seneca Falls Convention and three main activists: Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. However, history rarely discusses the women of the Haudenosaunee women who inspired these three incredible women. Since the creation of the United States of America, men have been the center of attention. They were given the right to vote, create laws, manage money, and had complete control over everything his wife and daughters “owned”. However, not all governmental systems were like this. The Haudenosaunee of New York, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy, was a democracy (possibly the world’s oldest still in existence) which was based on a matriarchal system. Women were not only included in conferences, had ownership of possessions, and could vote on matters, but they also had great authority and could even dismiss clan leaders.

Cady Stanton lived in Seneca, NY and had close contact with members of the Haudenosaunee and saw first-hand a better life for women. These interactions greatly impacted her view on the world, and she wrote many of her impressions of the Haudenosaunee women in the National Bulletin. Mott also spent time discussion politics and women’s roles in government

Elizabeth Cady Stanton one of the major activists of the suffrage movement

with these women. Gage admired the equality among men and women of the nation. To these three women, and the rest of the women who follow the very male-centered American cultural system, this way of life probably seems like heaven on Earth. Haudenosaunee women could divorce their husbands with ease and keep all their possessions and children. While in the event of an unlikely divorce, the American woman was left with nothing. American women did not have money, possessions, agency, or control over their physical being. They were little more than child baring objects for men to control. Wedding vows included a statement that the women would “obey” her husband, a statement which Cady Stanton omitted from her vows. Men were allowed to beat their wives, and rape or sexual assault did not exist within a marriage. Among all these problems, there was one overarching issue that needed to be addressed. In order to change or create laws to improve women’s lives, men had to take action. Not only were women forced to rely on men in their daily lives, but they also had to rely on them to better their stations. This was not so for the women of the Haudenosaunee. Clan mothers had the authority to take away male authority and change clan leadership. They were consulted at every conference, treaty meeting, and any other major political event. This female presence often made the American male representatives rather uncomfortable.

It is unfortunate that many of these First Nation women are nameless and not mentioned in history books. This nation had democracy and gender equality before the United States even existed. We as people who live under the US Constitution, owe our democracy to these democracy First Nations and we as women owe our rights and ability to vote to those women who through living their lives, inspired other women to make a change. Other cultures can offer so much information that can change the way someone looks at their own culture. Just like Cady Stanton, Gage, and Mott were inspired by the Haudenosaunee women, we can be inspired by many other cultures from around the world. It is important to consider other ways of life and view them not as an “other” but as something to seek new experiences from. Maybe we live better lives if we take a little outside inspiration.

It is unfortunate that many of these First Nation women are nameless and not mentioned in history books. This nation had democracy and gender equality before the United States even existed. We as people who live under the US Constitution, owe our democracy to these democracy First Nations and we as women owe our rights and ability to vote to those women who through living their lives, inspired other women to make a change. Other cultures can offer so much information that can change the way someone looks at their own culture. Just like Cady Stanton, Gage, and Mott were inspired by the Haudenosaunee women, we can be inspired by many other cultures from around the world. It is important to consider other ways of life and view them not as an “other” but as something to seek new experiences from. Maybe we live better lives if we take a little outside inspiration.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Sources: Yes Magazine and http://www.suffragettes2020.com/resources/native-american-and-american-indians

Brendan Cole Thesis: An Exploration of New Techniques

Written by Brendan Cole

The Monongahela Cultural Tradition is recognized as dating to the Late Prehistoric period, approximately A.D. 1150 to 1635. Additionally, it is identified as being present in southwestern Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, and northern West Virginia, where they lived in stockaded farming villages. The Monongahela culture was present during initial European contact, but there is currently no evidence that they were directly contacted by Europeans and were gone by the time settlers had reached Western Pennsylvania. The site used in this study is a Monongahela village site known as Squirrel Hill. It is a village site located in Westmoreland County. While the site was discovered in the mid-20th and there have been subsequent thesis studies and field schools conducted, there is still much unknown about the site.

The Monongahela Cultural Tradition is recognized as dating to the Late Prehistoric period, approximately A.D. 1150 to 1635. Additionally, it is identified as being present in southwestern Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, and northern West Virginia, where they lived in stockaded farming villages. The Monongahela culture was present during initial European contact, but there is currently no evidence that they were directly contacted by Europeans and were gone by the time settlers had reached Western Pennsylvania. The site used in this study is a Monongahela village site known as Squirrel Hill. It is a village site located in Westmoreland County. While the site was discovered in the mid-20th and there have been subsequent thesis studies and field schools conducted, there is still much unknown about the site.

The focus of this thesis is to explore the efficacy of non-invasive archaeological techniques to extract archaeological data. It is important to explore non-invasive/destructive methodologies because traditional archaeological excavation techniques are destructive in nature. Essentially whatever we dig up is removed from its original context, thus destroying that portion of the site. Preservation ethic, in short, tells us that if we do not need to excavate a site we should not. This not only preserves a non-renewable resource but saves them for the future when new excavation techniques, technologies, and research questions are developed.

Currently, there are technologies available to us that allow for data extraction without site disturbance or destruction. Two of those techniques, and the ones used in this thesis study, are ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and x-ray fluorescence (XRF). Separately these techniques have been proven to have great utility, but they have scarcely been used together.

This study aims to use both techniques in tandem at the Squirrel hill site. The GPR data will be overlain with elemental density maps constructed from the XRF. The primary goal of this will be to see where GPR anomalies and XRF elemental data overlap and where it does not. This will show areas of cultural activity and suggest what activities were occurring in those places. By doing this we will also gain an idea of village layout. All this information will not only help guide future research questions and excavation at the site, but it may also show the efficacy of using these methods together at other sites.

Follow IUP Anthropology on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram